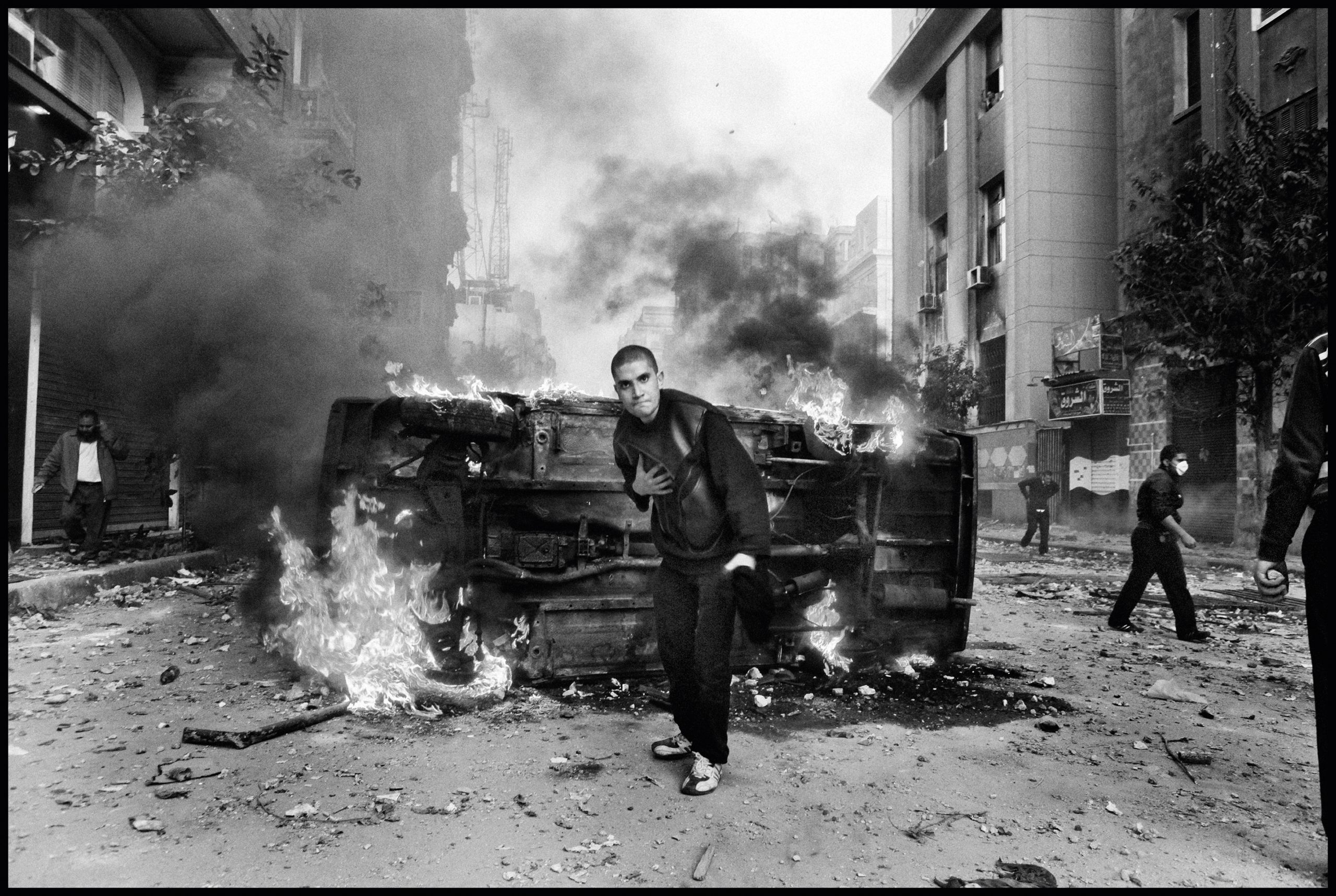

A miasma of tear gas hung over Cairo at the height of the battle for control of Tahrir Square. At night it drifted in through my open window a couple of miles away, along with the distant roar of the revolution. It took the protesters 18 days to dislodge President Hosni Mubarak, which they did on 11 February 2011. Until that moment he seemed to be an immovable feature on the political landscape of the Middle East, in office for nearly 30 years. To stay in the square they had to fight off Mubarak’s security forces, his thuggish supporters and even a bizarre cavalry charge by men oncamels.

Not every day was violent. Sometimes the square was a carnival, with platforms for speeches and music, men with handcarts selling sweet potatoes baked in wood-fired ovens made of old oil drums, and a sense of solidarity and mutual respect among Mubarak’s opponents that was unusual in Egypt. On violent days, bleeding protesters were treated at an improvised dressing station in a mosque on one of the streets behind Tahrir that used to be part of Cairo’s European Quarter. Surrounding it were crumbling, still graceful apartment houses built to emulate Haussmann’s renewal of Paris in the 19th century, with tall windows and balconies – many of their fine wrought-iron art nouveau balustrades were now crammed with junk.

In the streets, bandaged students sitting in the gutters made the place look like a tableau of some Parisian insurrection – Les Misérables on the Nile. During the worst stoning and brawling, casualties were coming in on improvised stretchers made of corrugated iron, or doors torn from their hinges, every 20 seconds or so. By the time Mubarak fell, so many half-bricks, fragments of paving and weaponised cobbles had been thrown that they made a shingle beach close to the Egyptian Museum, where Tutankhamen’s treasures were usually displayed. Young protesters wore blood-stained bandages long after they were needed, campaign medals commemorating a revolutionary moment that has long since passed.

I sat at a tea stall in Tahrir Square on a bench made of scrap wood with one of Cairo’s best-known bloggers. His glass of sweet mint tea stewed on an upturned plastic crate as he talked about how his compatriots had been inspired by the overthrow of Tunisia’s President Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali a few weeks earlier. If Tunisia, a small country we beat at football, could do it, he said, so could Egypt, the mother of the world.

[See also: Ten years on from Hosni Mubarak, what remains of the Egyptian Revolution?]

Anger and frustration takes years to build, but it only takes a moment for it to overflow. At the end of 2010 it came from the horrific suicide of Mohamed Bouazizi. He was a market trader in his mid twenties selling fruit and vegetables in Sidi Bouzid, a dusty and forgotten town in Tunisia’s interior. On 17 December 2010 inspectors from the local council confiscated his produce and, more seriously for a poor man, his cart and his weights, the only capital in his business. It was a humiliation too far. Later that day Bouazizi set himself alight outside the offices of the regional governor. He died on 4 January 2011.

Local protests went national, propelled by one of Tunisia’s trade unions organising rallies and tipping off the pan-Arab broadcaster Al Jazeera. Ben Ali had the gall to visit the dying Bouazizi in hospital. Ali’s men released a grim photograph of the president and his retinue standing uneasily at the bedside of a man entirely swathed in bandages. Many Tunisians saw a cynical attempt by a perpetrator to take advantage of his victim one last time. Ali and his wife fled to Saudi Arabia. They were so corrupt and grasping that the US ambassador, in a cable later released by WikiLeaks, called the family “a quasi-mafia”.

Revolution in Tunis and then Cairo spread across the Middle East live on 24-hour TV news and social media – which was still novel. Uprisings started in Bahrain, Yemen, Libya and Syria. In every Arab country, millions stirred and hoped. In 2011 the momentum of people power built until it seemed strong enough to knock over the other authoritarian Arab leaders. But those who had not been deposed learned a lesson; Mubarak and Ben Ali had not used enough violence. President Bashar al-Assad in Syria and Colonel Muammar al-Gaddafi in Libya would not make that mistake.

***

In 2011 currents that had been intensifying for years came together. One was the pressure of demography. Nearly two-thirds of Arabs were under the age of 30. They wanted jobs and freedom, not authoritarian and corrupt leaders who diverted national wealth to their cronies or their own offshore bank accounts, and who were prepared to jail or kill anyone who looked like a serious rival or critic.

When their populations were smaller, regimes could enforce a kind of social contract, offering jobs that paid just enough to ensure political quiet. In the 1950s and 1960s the mighty transmitters of Sawt al-Arab, the “Voice of the Arabs”, sent the views of one particular Arab, Egypt’s President Gamal Abdel Nasser, to radio sets in homes and cafés across the Arabic-speaking world. By 2011, however, it was impossible to monopolise the message and shut countries off from the outside world. The regimes’ distortions could not compete with the evidence on satellite television and the internet that there were better, freer ways to live your life.

Octopus-like domestic intelligence agencies spied on the people and, when a regime deemed it necessary, applied the squeeze, sometimes unto death. Their job was to build and maintain a barrier of fear. The barrier crumbled in 2011, for a while; a traumatic moment for Arab authoritarians. Since then they have worked hard to restore it.

***

So what happened to the hopes of 2011? Turning revolutionary zeal into government is never easy. Across the Middle East, secret police spent years crushing civil society. Laws and courts were hollowed out by dictatorship. Reformers had to start from scratch. Only Tunisia emerged with a new democracy.

Egypt’s tragic tale sums it up. The ousting of Hosni Mubarak was greeted with a great burst of joy in Tahrir Square. The next morning thousands of people turned up with brushes and buckets to clean the place up, symbolically reclaiming their country. The uprising had no real leaders, which made it feel democratic, but it meant that it could not produce a coherent strategy, or a credible candidate, for free elections in 2012. Instead, it came down to a contest between the two most organised forces in Egypt, the armed forces and the Muslim Brotherhood, which had campaigned since 1928 for a state based on the Quran. The Brotherhood won the election in June 2012 with its candidate Mohammed Morsi – but it lost the inevitable showdown with the army a year later. The generals had sacrificed one of their own, Hosni Mubarak, to save military power in Egypt. The Muslim Brotherhood was not going to be allowed to take it away.

[See also: Assad on trial]

President Morsi thought he could do a deal with his defence minister, Field Marshal Abdel Fattah el-Sisi. Instead, in July 2013, Sisi removed him from office and hit the Brotherhood hard. Many Egyptians were relieved; Sisi’s supporters held their own big demonstrations in Tahrir Square.

At least 2,000 civilians were killed in the months that followed, many of them supporters of the Muslim Brotherhood. During the summer of 2013 I saw soldiers and police fire into a furious crowd outside the army base where Morsi was being held. A man near me had the back of his head blown off. On another occasion I watched the dead and wounded shot by the security forces being brought to a mosque on carts and the backs of motor scooters from a big march in Ramses Square in Cairo. The wounded were treated on the ground floor. When they died, they were carried on men’s backs up an interior staircase that was slippery with blood and were laid out in rows in the mosque’s upstairs room.

The biggest single massacre happened in August when the security forces broke up a mass anti-government sit-in protest in Rabaa, a district of Cairo. At least 900 people were killed. In the heat and humidity of summer in Cairo, some of them were laid out for identification in a sweltering mosque that smelt of the decomposing dead. Families looking for missing relatives pulled aside shrouds stained with blood and with fluids oozing from the corpses.

A decade on, the hope that radiated out from Tahrir Square seems like some kind of distant, deluded dream. In Egypt, President Sisi runs a police state, tougher than anything Mubarak attempted, that has locked up tens of thousands of its opponents. Libya has suffered ten years of war since Nato-led air power enabled rebels to overthrow and kill Colonel Gaddafi.

In September 2011 David Cameron and the French president Nicolas Sarkozy paid a triumphal visit to the city of Benghazi in eastern Libya. It was their victory, too, and their defeat. Most Libyans wanted quiet lives. But removing Gaddafi and his cabal left a vacuum where his strange state once stood. Militias loyal to their tribes, or towns, or money, fought over what was left. Now, mercenaries working for Turkey, the UAE and Russia have joined them. The UN is trying, again, to create an interim government.

Disasters have replaced hope throughout the Middle East, from the Mediterranean to Yemen on the Red Sea. Ali Abdullah Saleh, the veteran leader who likened ruling Yemen to dancing on the heads of snakes, was forced out in early 2012. Since then, civil war, foreign intervention and hunger have turned Yemen into the world’s worst humanitarian disaster.

Saleh stayed powerful after leaving office. Army units loyal to him allied with the Houthis – a group that first emerged to oppose Saleh – to drive the internationally recognised government out of the capital, Sanaa. The Houthis killed Saleh when their pact broke down and he tried to switch to the Saudi side in the war. Jihadist extremists flourish in Yemen, as they have everywhere there is wreckage in the Middle East. The caliphate built in the ruins by the self-styled Islamic State was destroyed; now it is regenerating in parts of Syria and Iraq. The jihadists of Isis are back in their Toyota pickups and back to their old killing ways: “Beheadings, bombings, motorcycle suicide, assassination and kidnappings,” in the words of a Syrian researcher.

Should Western countries, somehow, have “done more” to help the protesters of 2011 and since? Foreign intervention in the Middle East over the centuries has always been in the interests of the powers doing the intervening. Invading Iraq in 2003 was a catastrophic decision. Barack Obama might have changed the course of the war in Syria in 2013, when the regime crossed his red line prohibiting the use of chemical weapons. Damascus emptied when the US bombs were expected; columns of laden army convoys left their camps to disperse into the countryside.

[See also: Mohamed Bouazizi: the faded icon of Tunisia’s Arab Spring]

A senior adviser to President Assad summoned me to the presidential palace, offered me tea and said: “Jeremy, you’ve been bombed by the Americans. What’s it like?” I said it would be noisy and largely accurate, though sometimes they hit the wrong targets (I had reported the killing by the US Air Force of more than 400 civilians in a shelter in Baghdad in 1991). Above all, the Presidential Palace was a place to avoid. Bashar al-Assad’s inner circle was very nervous about an American strike, and believed it had scored a victory over the US when it did not happen. The most disappointed were the rebels who wanted the support of the same air force that the Americans and British had lent to the Libyans. Two years later, in 2015, military intervention directed by Vladimir Putin saved Assad’s regime.

***

Before the pandemic I spent time speaking to a new generation of protesters occupying central squares in Baghdad and Beirut, who talked about new revolutions, and lives that weren’t dominated by corruption and sectarianism. In Iraq they continued demonstrating even when hundreds were killed by security forces and militias whom the demonstrators believed were working with them. The Lebanese, meanwhile, are desperate for deliverance from the former and current warlords who brought them to ruin.

Do not hold the would-be revolutionaries of 2011 responsible for the darkness that followed the Arab Spring. They didn’t have a chance. Better to blame the strongmen who set out to crush their hopes. For a few short months, change looked relatively painless, even easy. That was an illusion. Entrenched regimes do not surrender. Even the hopes of millions cannot beam down democracy. That requires time, education and institutions which are accountable to the public.

In 2011 they had none of that, but the uprisings changed everything. Regimes, or their retreads, fought back to keep power; they could not restore stability or legitimacy. The grievances of 2011 were never satisfied. Unemployment, repression and poverty still hurt and fester. A difficult, destructive process started ten years ago and did not end. Other attempts to overthrow the old order will arrive when desperation overcomes fear, without the illusions of 2011; and if the hope of that year revives, ruthless men will do all they can to kill it stone dead.

Jeremy Bowen is the BBC’s Middle East editor

This article appears in the 24 Feb 2021 issue of the New Statesman, Britain unlocks