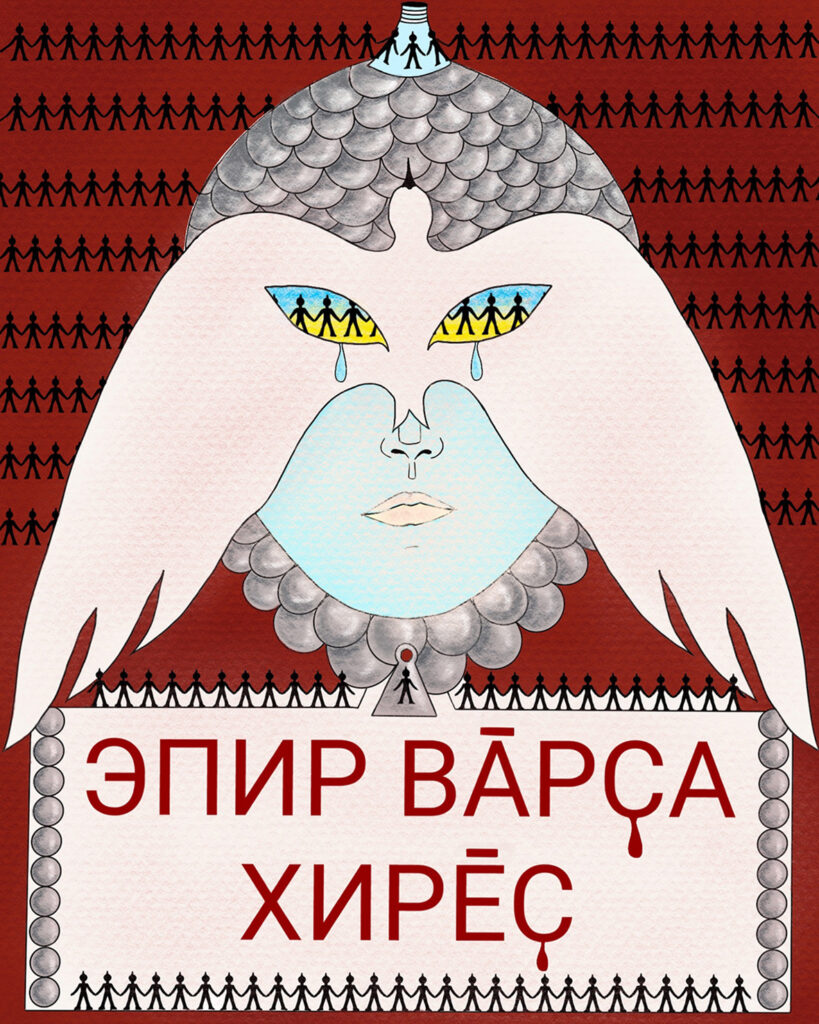

When the artist Polina Osipova saw photos of civilian bodies strewn across the street in the Ukrainian village of Bucha, she found she had no Russian words left to describe the atrocity. Instead, she sat and wrote an anti-war message in her mother tongue: Chuvash.

“[Chuvash] is much freer now than Russian,” says Osipova, who grew up in a village in central Russia before moving to St Petersburg. All of her family are Chuvash, an ethnic group with its own distinct culture and roots to the west of the Volga river. It also has its own language: one of more than 135 spoken among the almost 200 distinct nationalities that live across Russia’s vast territory. According to the 2010 census, 81 per cent of Russia’s population, or roughly 111 million people, are white, Slavic Russian. The remaining 19 per cent belong to ethnic minority groups, including indigenous peoples of colour from Asia and the far north.

“I believe that saying ‘no to war’ in your own native language reinforces the meaning of those words,” Osipova says. “Russian propaganda is doing its best to show that people who oppose the war are in the minority. As an indigenous person, in my own native language, I am trying to show that to be false.”

Osipova is not alone in turning to Russia’s long-overlooked minority languages to express her rage. The war in Ukraine has left many Russians inconsolable, but a violent crackdown on civil rights since the invasion began means that expressing opposition is hazardous. Early on in the conflict the Russian government announced that anyone who referred to the invasion as a “war” — rather than using the Kremlin’s preferred term of “special operation” — risked a jail term of up to 15 years. A number of Russians have been detained or fined under hastily passed laws designed to prosecute those who “discredit” Russia’s armed forces.

[See also: TV protest illustrates widespread unease with Putin’s war]

In this new reality Russia’s minority languages provide a novel way to express unrest, while circumventing the country’s increasingly violent censorship. T-shirts, Instagram posts and artworks have appeared online in a cacophony of tongues (although largely written in Cyrillic, an alphabet which was imposed on many of Russia’s minority language during Tsarist and Soviet rule). They all bear a single message: no to war.

“The idea seemed to come to everyone at the same time,” says Sonya Ahn, founder of the magazine Agasshin. Created as a beauty zine serving Russians of colour, it is now publishing a series of anti-war posters in minority languages such as Udmurt and Komi. “In the second week of the war, I started seeing anti-war posters in [minority languages like] Buryat and Kalmyk on Instagram,” says Ahn. “At first, it really was about finding a safe way to express your opposition.”

Activists hope that their multilingual work will help to spread anti-war opposition across their communities while avoiding the scrutiny of the security services. They also hope it will spotlight the impact that the war will have on Russia’s minorities. Many are concentrated in so-called “national republics”: regions traditionally linked to certain ethnic groups, but which don’t enjoy the same economic opportunities as Moscow or St Petersburg. Poverty provides a strong impetus for young men from Russia’s ethnic minorities to join the army; they are often over-represented on the front lines.

“A large number of Buryats are now fighting in Ukraine, because it’s almost the only way for these young guys to earn money,” says the Buryat-Chinese artist Yumzhana Sui, who makes anti-war work in the Buryat language. Now living in Mongolia, she grew up in Ulan-Ude, the capital of the eastern Russian republic of Buryatia. “Despite everything, I think that people [in Buryatia] will start to open their eyes. Buryatia is quite small; people know each other. When you start to find out that your friends, their brothers, nephews and acquaintances were sent to their deaths like cannon fodder, something switches in your mind.”

Other activists see parallels between Russia’s imperialist conquest of Ukraine and the experiences of their own communities at the hands of Tsarist forces or Soviet officials, who suppressed regional languages and cultures in favour of the Slavic, Russian-speaking “ideal”. For them, speaking out against the war is imperative for tackling Russia’s colonial legacy.

“At the beginning of the war, I asked other Chuvash people: should we die for the insane ideas of people who have been destroying our own culture for centuries?” says Osipova. “It’s important to have anti-war slogans in indigenous languages, but any education on people’s culture and roots is anti-war in essence, because it’s a fight against imperialism.”

Ahn agrees. “People are surprised at what is happening in Ukraine now. This, unfortunately, does not surprise me at all, because since childhood I know how white Russians treat those who do not look like them, who speak a different language, who grew up in a different culture.”

For now, activists hope that the Russian government’s dismissive attitudes towards ethnic minorities will work in their favour as they try to avoid repression. “This is Russia, [the authorities] can ban anything if they want,” says Ahn. “But they might struggle to type out the words they want to ban [in minority languages] — I doubt they’ve even got the right letters downloaded onto their keyboards.”

All are determined to make their own small act of protest: calling Putin’s war what it actually is. “It’s a case where being a ‘minority’, something ‘small’ and insignificant, is actually useful,” says Ahn. “War is war. Things should be called by their proper names — even when you’re threatened with jail time for doing so.”

[See also: Scared, hopeless and silent, anti-war Russians are pessimistic about mass protests]