Earlier this month, my home state of Virginia elected a Republican governor for the first time since 2009. Joe Biden won Virginia by ten points: many pundits were quick to warn of doom for the Democrats in next year’s midterm election if it swung back to the right. It was telling in this election that in the time of coronavirus, Covid was ranked behind the economy and jobs as the second most important issue facing the state. Education came third.

Nothing particularly outstanding is going on in terms of education in the Commonwealth, as Virginia is known. State school students continue filling in standardised test forms with no 2 pencils just like they do all over the country. But voters in Virginia weren’t responding to how students are being taught, but rather to the perceived threat of what – namely, critical race theory (CRT).

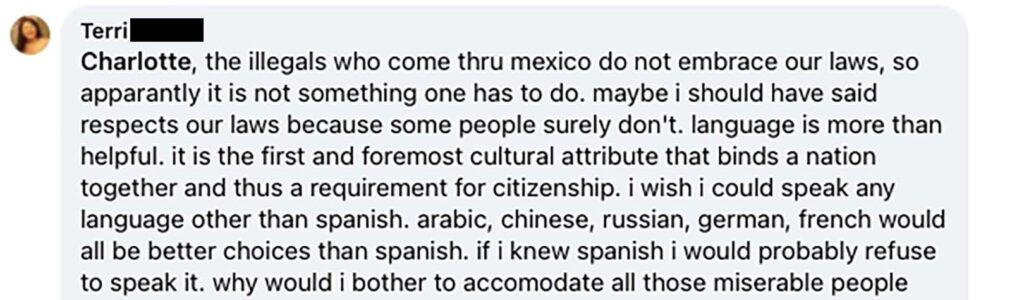

This screenshot is one of many racist rants that my aunt Terri, also from Virginia, used to leave on my Facebook wall. Terri was an avid user of social media, but sometime around June 2020 her normal Facebook activity stopped. She was being sued in federal court by a local housing charity. It had received several complaints that Terri was rejecting potential renters for her properties who were disabled or had children. All the racist and Trump-supporting posts had been erased, but in February they started popping up again. I speculated she had wiped out her social media because she didn’t want anyone poring through it while she was going through a federal lawsuit.

In a recorded phone call to a potential renter, Terri said: “I get calls all the time from people who get a disability check. Not a darn thing wrong with them. Not nothing. Nothing’s wrong with them, like, you know, I’ll ask, ‘Are you in a wheelchair? Can you do stairs?’ ‘Oh, it’s not that kind of disability.’ ‘What is it?’ ‘I’m depressed.’ ‘Really? Well so am I now that I know what my tax dollars are paying for.’”

As part of the settlement, Terri had to sell her remaining rental properties, pay $25,000 to the housing charity, and agree not to be a landlord for the next five years. I never got the opportunity to discuss with my aunt her views on CRT, but I can guess what she would have said. She’d probably say it was some form of reverse racism and fall back on the “bootstrap” mythology that so many Americans are taught in civics classes – that we can get ahead if we just try hard enough. In her view, minorities just weren’t trying hard enough.

Terri wouldn’t be alone in thinking this way. A poll taken earlier this month showed that 43 per cent of respondents who identify as Republicans said they are against the teaching of historical racism in public schools. This would require a lot of literal whitewashing of Virginia’s history, seeing as how it was the state that sold the first enslaved people and was the capital of the southern Confederacy in the American Civil War.

The reason I never got to talk about CRT with my aunt is because she died suddenly of a heart attack the night after she signed the contract to sell her first rental property. Perhaps the stress from settling a lawsuit was enough to make her heart stop beating.

For as far back as I can remember, my aunt was in some sort of physical or emotional pain. When I was a teenager struggling with bulimia, she’d take me aside at Thanksgiving dinners and tell me how she buried her own stress in compulsive eating. There were some family gatherings where she ate so much that she couldn’t get up from her chair. She also suffered from chronic pain that made it difficult for her to go up and down stairs. Although my aunt had health insurance, what she was doing to her body outpaced anything doctors could do for her.

Chronic pain is not uncommon in the US. The US Center for Disease Control reported that in 2019 one out of five Americans reported chronic pain, and 7.4 per cent felt so much pain that it limited their life or work activities. In a 2017 survey of 31 countries, Americans reported the highest level of pain, with 34 per cent saying they “often” or “very often” feel pain. And the future doesn’t look good. Research from the UK in 2020 shows that lockdown made those in chronic pain feel even worse.

Anne Case and Angus Deaton, both of Princeton University, looked at the rising rates of the “deaths of despair” in the US in their book Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism. Between 2006 and 2016, 400,000 Americans died by suicide and another 400,000 from accidental drug overdoses, of which a fifth were related to opioids. Case and Deaton found that these deaths were higher among middle-aged white Americans without a college degree. They also found that this same demographic is suffering from high levels of chronic pain, to the extent that middle-aged Americans are reporting higher levels of pain than the elderly.

In the US, pain and politics seem to go together. A paper from Pennsylvania State University looked at the correlation between deaths of despair and voting for Donald Trump in the 2016 election. The author, Shannon Monnat, found that Trump outperformed the 2012 Republican candidate, Mitt Romney, in counties that reported the highest levels of drug, alcohol and suicide deaths. The trend was particularly pronounced in the industrial mid-west (the so-called rust belt): Trump outperformed Romney by an average of 16.7 per cent, compared with 8.1 per cent in the counties reporting the lowest mortality.

The reasons are difficult to pin down with empirical research, but theories abound. After the 2016 election, two storylines began unfolding. One was that many poor Americans looked to Trump as a mega-wealthy tycoon who, through some sort of political alchemy, would make them rich. Another was that white Americans had grown fed up with seeing so many black and brown people gain in social prominence and wanted to vote for the racist-in-chief who would make them feel special again.

The “left behind” narrative was described by Arlie Hochschild in Strangers in Their Own Land as a feeling of looking around and not knowing where you belong. She put her finger on 1970 as the year the American Dream stopped working for most people. Those born earlier saw their incomes rise progressively over their lifetimes. Those born after 1970 experienced the first ever drop in upward mobility.

The steepest drop was felt by the same people who are now dying deaths of despair and living in chronic pain. For middle-aged white Americans with only a high school diploma, the turning point was 1998 – when mortality rates started reversing and grew by half a per cent each year. These Americans are not dying at a faster rate simply because they cannot access healthcare or pay for prescription drugs. They are dying because of a collective harm that is born from living in a society where the once-promised prosperity remains just out of reach. The good jobs that allowed a white man without a college education to feel a sense of dignity and provide for his family are no longer available. They have either been replaced by automation or don’t pay enough to make rent.

Michael Marmot, professor of epidemiology and public health at University College London, has spent time looking at the health ramifications of working what he calls high-demand/low-control jobs. In his study of British civil servants, he found strong evidence that having high amounts of stress and no control over how you do your job correlated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, mental illness and work absences.

“If you were working in a steel company and a member of a union, and now you work in a coffee shop for low wages or drive a delivery van in the gig economy and your income and job stability have gone down, you can imagine being thoroughly fed up, having a feeling of social and economic malaise,” said Marmot.

“Then, if somebody says falsely you had been replaced in your job by somebody of colour, it can lead to racial resentment, even susceptibility to white supremacy.”

Virginia, like many places, did not have an easy 2020. Drug overdose deaths increased by 41 per cent, compared with a national average of 30 per cent. Faced with rising inflation and economic uncertainty, it is unlikely that the health of many middle-aged white voters will improve. But instead of focusing on the things that are making them sick – such as low wages, high housing and medical costs, and air pollution – Virginians went to the voting booth thinking about CRT.

My aunt, like many Republicans, believed in personal responsibility. She felt society was never at fault for the actions of individuals because in her mind, “equal” meant that good life choices were just as easy to make for Donald Trump’s sons as they were for George Floyd. It’s easy to look back over Terri’s life and think that she got what she deserved, but no happy, healthy person would damage their body to such an extent that walking three city blocks becomes impossible.

I’ll never know exactly what made my aunt feel so miserable that she turned her own pain against the people around her, but I suspect the origins lie somewhere in her own trauma. Something must have happened that made it easy for a demagogue to come along and blame an outside group for everything that was wrong in her life. For Terri, prejudice became the sweetest opioid.

[See also: What a Republican win in Virginia means for Joe Biden]