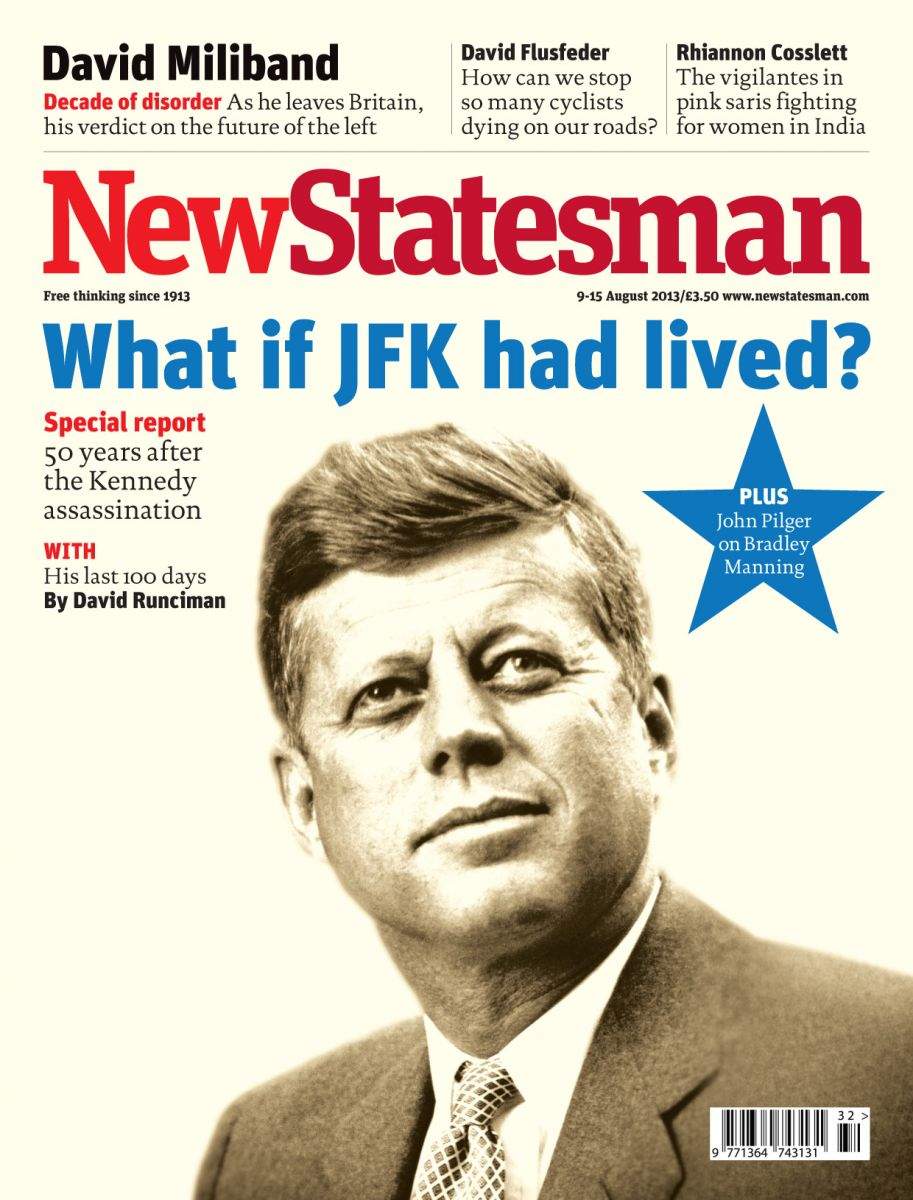

You are invited to read this free preview of the upcoming New Statesman, out on 8 August. To purchase the full magazine – with our signature mix of opinion, longreads and arts coverage, plus columns by Laurie Penny, Will Self, Caroline Criado-Perez, Rafael Behr and John Pilger, as well as our cover features on John F Kennedy and all the usual books and arts coverage – please visit our subscription page

You are invited to read this free preview of the upcoming New Statesman, out on 8 August. To purchase the full magazine – with our signature mix of opinion, longreads and arts coverage, plus columns by Laurie Penny, Will Self, Caroline Criado-Perez, Rafael Behr and John Pilger, as well as our cover features on John F Kennedy and all the usual books and arts coverage – please visit our subscription page

People sometimes ask why – or lament that – the financial crisis of 2008 has not led to an upsurge of support for the centre left. One answer is that in many countries parties of the centre left were in government, and so got the blame, yet this is insufficient. In truth there was a major market failure and in particular a failure of under-regulated markets. But there was state responsibility, too. Moreover, as Stan Greenberg has written, “a crisis of government legitimacy is a crisis of liberalism”. That is why reforming the state as well as reforming the market is a necessity, not a luxury. Where centre-left parties do get elected, they quickly find that, while the nostrums of what Tony Judt called “defensive social democracy” can strike a chord when a party is in opposition, they are insufficient for government. The welfare state needs defence in the face of unfair attacks. But it also needs reform. Inequality is undoubtedly a modern menace exacerbated by austerity, but macroeconomic policy and even full employment will not tackle its roots. Those at the bottom need a voice, but the middle class is also feeling squeezed. The public sector and its services have been a civilising force in western societies, but they need to operate very differently to meet the twin challenges of changing public expectations and needs and limited public funds.

Francis Fukuyama has laid down the challenge as follows: “It has been several decades since anyone on the left has been able to articulate, first, a coherent analysis of what happens to the structure of advanced societies as they undergo economic change and, second, a realistic agenda that has any hope of protecting a middle-class society.”

We who are on the centre left should take this challenge seriously. There is not an “off-the-shelf” model of social democracy, though there are powerful examples of what can make a positive difference (as well as what doesn’t). The starting point for the modern left has to be to understand the new world.

There are many ways of describing the changing context for what the US columnist David Brooks has called the debate about how to rejuvenate mature industrialised societies. To my eye, there are four key global changes under way that explain why this feels like a decade of disorder.

There is the shift in economic power from west to east (and to some extent from north to south), as outsourcing and what Al Gore calls “robo-sourcing” (that is, technological change) alter the economic prospects of millions of people. As many as 50 million people a year are joining the global middle class in Asia, while norms of employment are being overturned. This has huge domestic consequences in industrialised societies, but is also creating a new power structure in the international system.

There is the resource crunch, which predated the credit crunch and is exemplified by a mismatch in the supply and demand for resources that is driving up their prices. Shale gas discoveries in the US are important but they do not invalidate this issue. The oil price remains high and non-oil commodities have risen fast enough in the past decade to eradicate the price cuts of the previous hundred years. As the urban middle-class global population is continuing to grow, it is hard to see this trend going into reverse.

There is the radical extension of the open society to the nooks and crannies of economic and social life, public and personal. This is fuelling democratic revolutions in the undemocratic world and frustration with democracy as conventionally practised in the established democracies. Across the public-private divide, the bar for the legitimate exercise of authority is being raised. This is a good thing.

And then there is the pressing nature of interdependence, local and international, that demands new forms of co-operation at precisely the time when people want more power for themselves. The Lehman moment showed that the pre-existing definition of which institutions posed systemic risk was not properly thought through.

It is the interaction of these global changes that has reframed the political equation in western democracies. The welfare state is costing more, but investment in supporting wealth creation constitutes an increasingly urgent claim on public funds. Wages are being squeezed and immigration is causing resentment. There is a crisis of employment and opportunity among young people, but they don’t vote in heavy numbers, so politics is skewed towards the old. The shift to low carbon is a necessity, but there is a collectiveaction problem when global negotiations are stuck. Societies have become more diverse in cultural as well as racial terms, and this has opened up a challenging axis of division in politics, which makes the construction of coherent electoral and governing coalitions more difficult. The putative conflict between cosmopolitans and communitarians has been a real one.

In the 1990s it seemed that economics and politics were pushing in the same direction. Globalisation was driving down inflation by producing goods in developing countries at low prices to satisfy western demand; education and training were offering opportunities for greater social mobility; social justice seemed like the counterpart of economic efficiency. The heart of the conundrum facing centre-left parties today is that economics and politics are systematically pulling in opposite directions. The economics calls for more sharing of sovereignty, but the politics is more nationalist or localist. The economics calls for more migration, the politics for less. The economics says switch welfare spending from the old to the young, but the politics of that are horrible. And so on.

Meanwhile, politics itself is increasingly seen as broken – and not merely seen as broken but actually broken. This is not just about corruption scandals. It is also about political systems that, for too many people, have lost their capacity to engage and include. Party systems are controlled by small groups (President François Hollande’s exemplary election by open primary excepted). Big money creates a sense of popular disempowerment. Parliaments are gridlocked and enfeebled. For parties of the left, which take pride in the power of politics to check the abuse of power in markets, these are not peripheral concerns. They are the basis for rethinking.

It is not that the centre left is wrong to continue to see the importance of Keynesian insights, or wrong to see an important role for government in economy and society, or wrong to defend the poorest, who rely on the welfare state. It is that these articles of faith are insufficient for navigating the rapids of government.

I was once told by a Swedish friend of mine – a successful politician in his own right – that good politics starts with empathy, then proceeds to analysis, then sets out values and establishes the vision, before getting to the nitty-gritty of policy solutions. A lot of politics focuses on the last point, but maybe that is why it fails to connect to a lot of the public. It seems to me that if this is right, three sets of issues, interlocking in nature, will be defining for the future of the centre left.

The first is how we respond to the people’s desire for more protection from risks beyond their control – without falling into the trap of big-state solutions that are neither affordable nor deliverable. These can be global risks of an economic, environmental or securityrelated nature. They can be personal risks, such as unemployment, dementia or crime. In each case the old mechanisms for collective insurance against risk through the state are under pressure.

The second is how we meet people’s expectations for more power and control over their own lives – at a time when interdependence and inequality are making this seem like a pipe dream. The sense of disempowerment can be economic, in workplaces that lack the collective power of trade unions and where employee satisfaction and opportunity are limited. It can be social, in communities where crime or neglect sap individual and collective strength. Or it can be in public services, where budgets or decisions are out of the reach of the people who use the services.

In truth, the “Third Way” discussions of the 1990s were too weak in addressing issues of economic power, in the workplace and elsewhere. There seemed to be sufficient common ground to facilitate win-win solutions. But the stagnation of wages, among other matters, has shown that this perception was optimistic at best. Economic empowerment needs a harder edge.

The third is how to foster a sense of belonging when people are more mobile and identities more complex. This is partly, but not only, about immigration. It is also about the loneliness of too many elderly people and the lack of security of people of all ages.

Each of these areas of study captures socialdemocratic concerns with equity and mutuality. But they look at them in different ways, through the lens of the way people lead their lives, rather than the overall structure of society. What is more, they challenge the stilldominant paradigm of Anglo-Saxon politics: for or against state or market, for or against public or private sector. They speak much more clearly to the continental European notion of a social-market economy, in which public values and mores define market rules and norms, and in which the state is respectful of private enterprise and personal liberty. Where Labour had ended up in Britain by 2010 – too hands-on with the state and too hands-off with the market – shows the perils of not getting this clear.

So what is the way forward? Away from the tactical battles that dominate day-to-day politics, the lessons from the successes – like that of President Obama – and the struggles, seem to me as follows.

The first is that, while fiscal stimulus may be a short-term remedy for low demand, fiscal prudence is a medium-term necessity. Keynesianism is after all a hard taskmaster.

The second is that the politics of production requires social democrats to address the structural challenges to western economies as engines of wealth creation. Sometimes this challenge is reduced to a debate about the importance of “manufacturing”, but that is not enough, as the border between manufacturing and services becomes blurred, and as services take up a much larger share of the economy and require ever higher degrees of skill.

The third is that the tendency of markets towards inequality and instability needs to be countered by action upstream in order to curb abuse of power, and to empower citizens and employees with rights, information and control. “Predistribution” does not fit on an electoral pledge card, but the idea is right and so is the challenge of developing new ways, either through individual rights or collective organisation, to tilt the balance of power towards ordinary people.

The fourth is that the state needs to do more with less, and that requires big reform. Reform is one of those words that can lose meaning through excessive and loose use. But for social democrats the specifics of decentralisation of power, transfer of budgets from managers to people, integration of back offices, and challenge from private- and voluntary-sector providers should all be geared towards the goal of a public sphere that can serve its founding purpose: representing the public and its interest against threats of injustice and insecurity. That the Tories will try to use their bungled NHS changes as an excuse for an assault on the very universality of the health service shows how high the stakes are.

The fifth lesson is that fighting globalisation is futile and damaging, but the processes of global integration nevertheless need to be managed by regional co-operation in the absence of stronger global governance. It is striking that, despite the travails of the European Union, around the world there is a tendency towards regional association – in the Pacific Alliance in South America, for example (its GDP is 20 per cent greater than Brazil’s). This is the way for medium-sized states to have influence.

The sixth message is that the challenge for parties and politics is as big as the challenge to policy. Assembling a winning coalition is one thing; holding it is harder. That makes the achievement of the Obama campaign quite remarkable. He was helped by his opponent, but he made his own luck through a drive street by street and voter by voter to maintain his winning coalition. Presidential elections are different from parliamentary systems, but there is read-across nonetheless.

Politics is more open than for many years – and there is a lot to fight for. I will be fighting a different set of battles, but I leave Britain confident that Labour can win.

Give a gift subscription to the New Statesman this Christmas from just £49

Content from our partners

You are invited to read this free preview of the upcoming New Statesman, out on 8 August. To purchase the full magazine – with our signature mix of opinion, longreads and arts coverage, plus columns by Laurie Penny, Will Self, Caroline Criado-Perez, Rafael Behr and John Pilger, as well as our cover features on John F Kennedy and all the usual books and arts coverage – please visit our subscription page

You are invited to read this free preview of the upcoming New Statesman, out on 8 August. To purchase the full magazine – with our signature mix of opinion, longreads and arts coverage, plus columns by Laurie Penny, Will Self, Caroline Criado-Perez, Rafael Behr and John Pilger, as well as our cover features on John F Kennedy and all the usual books and arts coverage – please visit our subscription page