Sci-fi geeks with a fondness for the early 1990s will be familiar with Data, a loveable robot who serves as Captain Picard’s second officer aboard the USS Enterprise in Star Trek: The Next Generation.

The show’s writers described Data as a fully-functioning male android. Although he is “self-aware” and “sapient”, he is unable to feel emotion like his human counterparts. Data has no real childhood to speak of that would lead him to do such things as hate his dad and grow up to join a hippy commune; get his heart broken and binge drink for a week; or feel the spark of inspiration that would make him write this essay. He does have the capacity to make decisions, but they are not based on intuition and past emotional experiences. Rather, they are cold hard calculations of solidified facts.

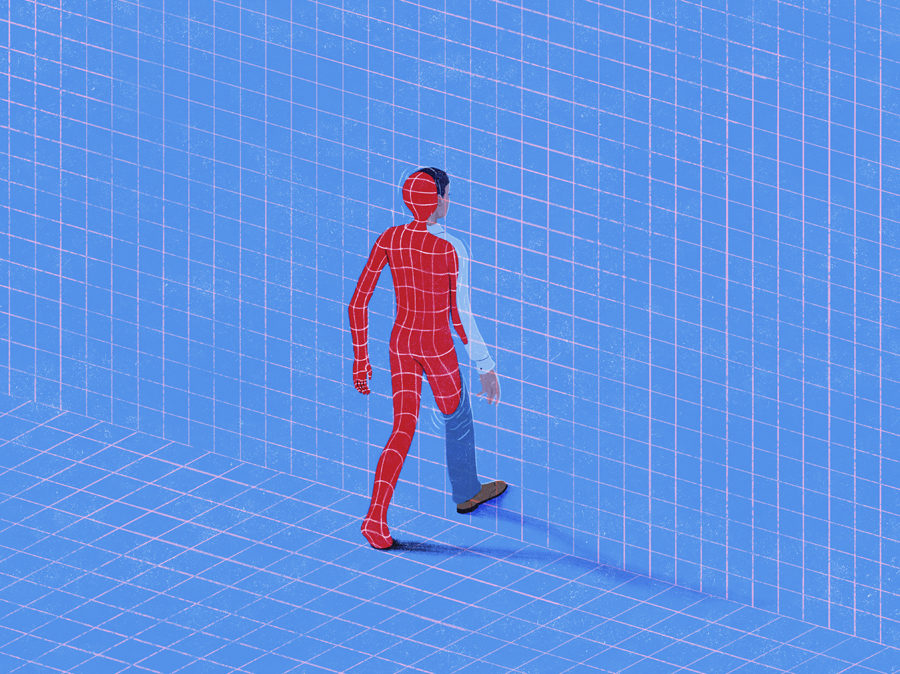

Were Data not a fictitious character there would be some in the scientific community who would say he is as smart, if not smarter, than a human being. His creation would pass a golden milestone whereby computer scientists could point to him and definitively say a “God moment” had taken place, when human beings have created machines that are smarter than themselves. For the moment Data and other robots like him exist only in the realms of imagination, but the discussions about whether robots are already intelligent or sentient, or even if intelligence means a machine must be sentient, are being hotly debated among computer scientists. The problem is that while science can create the algorithm that would make a robot describe an emotion, it cannot determine what makes someone human in the first place. For that we need to turn to philosophy.

[See also: Elon Musk’s useful philosopher]

The problem in asking whether a robot will ever be as smart as a human is in how we frame the question. For starters there are many forms of intelligence – and philosophy attempts to answer the questions of what we mean when we talk about intelligence and self-awareness. Responding to whether humans are fully in control of their own thinking, Descartes famously asserted “I think therefore I am”. Although a machine could recognise its own existence in a mirror, it cannot feel that existential dread that death is an inevitability. And while machines could converse with one another, they could never feel the emotional frustration that led Jean-Paul Sartre to conclude that hell is other people.

Some computer scientists have already argued that machines will never be able to reach human intelligence. In 1976 Joseph Wiezenbaum, a professor of informatics at MIT, made a distinction between computer power and human reasoning. He argued that computers will never be able to develop human reason because the two are fundamentally different things. Human reason would refer to Aristotle’s interpretation of prudence as the ability to make the right decisions. A computer could be programmed with a moral code, but it would always lack the ability to spontaneously make decisions based on its own interpretation of right or wrong. Weizenbaum argued that human reason could never be algorithmic, and therefore computer power could not replace human reason.

A central plot point to Data’s character development in Star Trek was his increased desire for the human emotional experience. In one episode he receives an “emotion chip” from his creator that allows him to feel the depths of all human emotions. For lack of a better word this chip comprises Data’s soul and is not something that could be created by a computer programmer. Instead, it is defined by centuries of constant questioning of what makes human beings more than machines.

[See also: the New Statesman’s Agora philosophy column: a marketplace of ideas]