This is as bad a day for the British economy as I can remember. The Bank of England, through its actions and loose talk by governor Andrew Bailey, is driving the UK into a deep recession. Their forecasts suggest something truly horrible to come before the end of the year.

It doesn’t help that the UK has no permanent prime minister and that we don’t know who will be chancellor and be tasked with stopping the recession turning into a depression. The markets will not like the lack of preparedness and the pound, increasingly likened to an emerging-market currency, is especially vulnerable.

This is the first time I have ever seen the Bank of England use the word “recession” in its forecasts. In its report in August 2008 when the UK was already in recession it never used the word: today the word was used nine times.

The bank today raised interest rates from 1.25 per cent to 1.75 per cent, which is the biggest rise since 1995. At the same time, it predicted a devastating recession that will be longer and deeper than the 2008 crisis.

[See also: Only radical solutions can tackle this cost of living emergency]

The forecast suggested there would be seven quarters of negative GDP growth (from Q4 2022 through to Q2 2024) with output falling by 7.1 per cent. This compares to the 2008 recession when GDP fell by 6.1 per cent across five quarters. And should the Monetary Policy Committee raise rates by as much as Liz Truss wants the situation could become even worse.

The MPC also forecast that the unemployment rate would rise from 3.7 per cent to 6.3 per cent over the next three years, perhaps as high as 9 per cent. The chances are that it will surpass 10 per cent (unemployment peaked at 8.4 per cent in 2011 following the financial crisis).

We should recall that Margaret Thatcher entered office with unemployment at 5.3 per cent and that rates were sharply increased to control inflation. Unemployment then didn’t return to that level for 20 years and was in double digits from 1981-1987, peaking at 11.9 per cent in 1984. Here we go again.

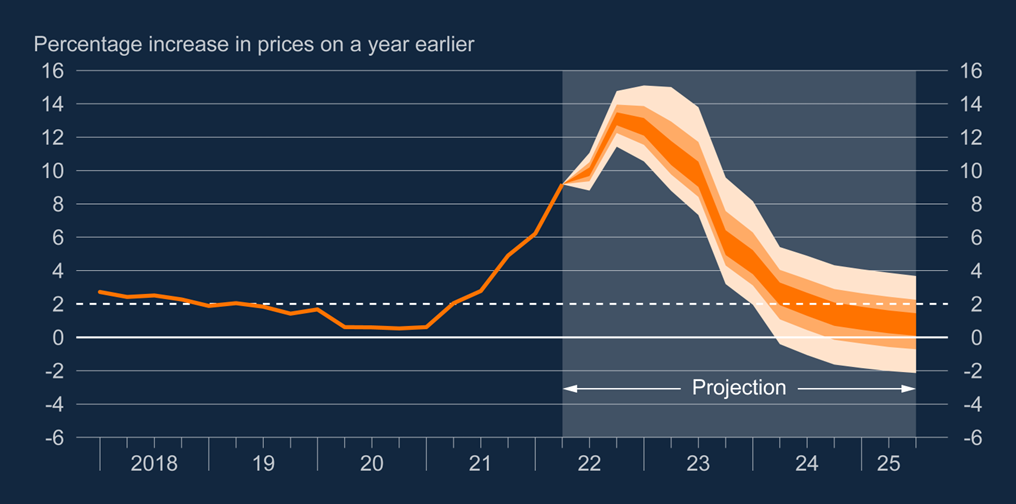

Another major concern, as the chart below shows, is the MPC’s warning that deflation is a real possibility (remembering, of course, JK Galbraith’s observation that “the only function of economic forecasting is to make astrology look respectable”).

We have data spanning 800 years from the Bank of England and for 340 of those years prices fell: historically, deflation is the most likely outcome from a burst of double-digit inflation.

The chart is taken from the MPC’s Monetary Policy Report. Forecasts are measured with error and so what they expect to happen in the future is drawn as a band rather than a line. It is clear that, from the middle of 2024, there is a significant and not small prospect that prices will start falling. Central bankers do not have the tools to deal with deflation. And, in fact, they are forecasting that inflation will quickly fall back towards the bank’s 2 per cent target. So why raise rates at all?

As she prepares for power, Liz Truss would do well to remember that voters throw out governments that cause recessions.

[See also: What does stagflation actually mean?]