John le Carré’s 1974 novel Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy is a time capsule from the England I was born into: the land of Edward Heath, the Barber boom and the oil shock, the three-day week, and miners’ strikes that won. Its story of an old spy, George Smiley, hunting a Soviet “mole” in the “Circus”, was largely reviewed as a thriller. But by taking the epic treachery of Kim Philby, the intelligence officer who had spied for Moscow in the 1940s and 1950s, and extending it into the crisis-ridden 1970s, Le Carré also symbolised an establishment in terminal decay.

Around this time, Heath’s top civil servant, William Armstrong, allegedly described the role of the civil service as “the orderly management of decline”. No wonder the Spectator‘s reviewer thought he detected Smiley’s creator’s “hatred of his country’s decline, and the hatred of those responsible by their lack of vitality for it”. Today, such talk is back. So: is “decline” still detectable in the places Le Carré used to evoke it 50 years ago? One recent Saturday, I walked through London, tracing locations from the novel to find out.

After lunch at a pub on Gloucester Avenue in Primrose Hill, in the north of the city, I walked to St Mark’s Crescent, overlooking the Regent’s Canal. This is where Le Carré located the Circus safe house in which Smiley traps the mole. He turns out to be a pre-war Oxford golden boy, who started his career on the imperialist right, with “grand designs for restoring England to influence and greatness”. What drove him to spy for the Soviets was his loathing of America, and of England’s humiliating postwar slide through the Suez Crisis into mediocrity. He hates his country’s apparent decline, but his betrayal hurries it along. On a rail bridge over the canal, someone has now sprayed: “BREXIT WAS SOLD 2 U BY LIARS.”

I then headed west, past the mansion blocks edging Regent’s Park, to St John’s Wood, where Smiley has a tense exchange in a pub garden with one of his Circus colleagues. Roy Bland is the son of a communist Cockney docker, who reacted to his boy’s educational feats by beating him up for selling out to the ruling class; Bland is in MI6 to get his own back. There were a lot of men on this kind of personal odyssey in the 1970s, such as Alan Walters, the son of a communist grocer in Leicester, who in 1981 would become Margaret Thatcher’s monetarist commissar. Or the philosopher Roger Scruton, whose left-wing dad Jack’s response to Roger winning a place at Cambridge was to stop talking to him.

When Le Carré was writing Tinker Tailor in the early 1970s, what we remember as the great Thatcherite sea-change of the 1980s was already under way. Bland is revolted by England’s burgeoning materialism; none the less, after years of miserable undercover work behind the Iron Curtain, he is keen to get his share. “It’s the name of the game these days,” he taunts Smiley, “you scratch my conscience, I’ll drive your Jag, right?”

I passed a house with a Rolls-Royce and a Ferrari parked outside. Today, the prosperity Bland bemoans has redefined the scale of modern wealth. On a street where the big, plush houses were having cosmetic work done, I stopped at a gastropub. At the next table, a man and two women – thirties, confident – were talking about work: a male employee who wouldn’t shut up, and a female colleague who offered too much of her backstory. The guy who wouldn’t shut up had been got rid of.

[See also: Cormac McCarthy’s art of war]

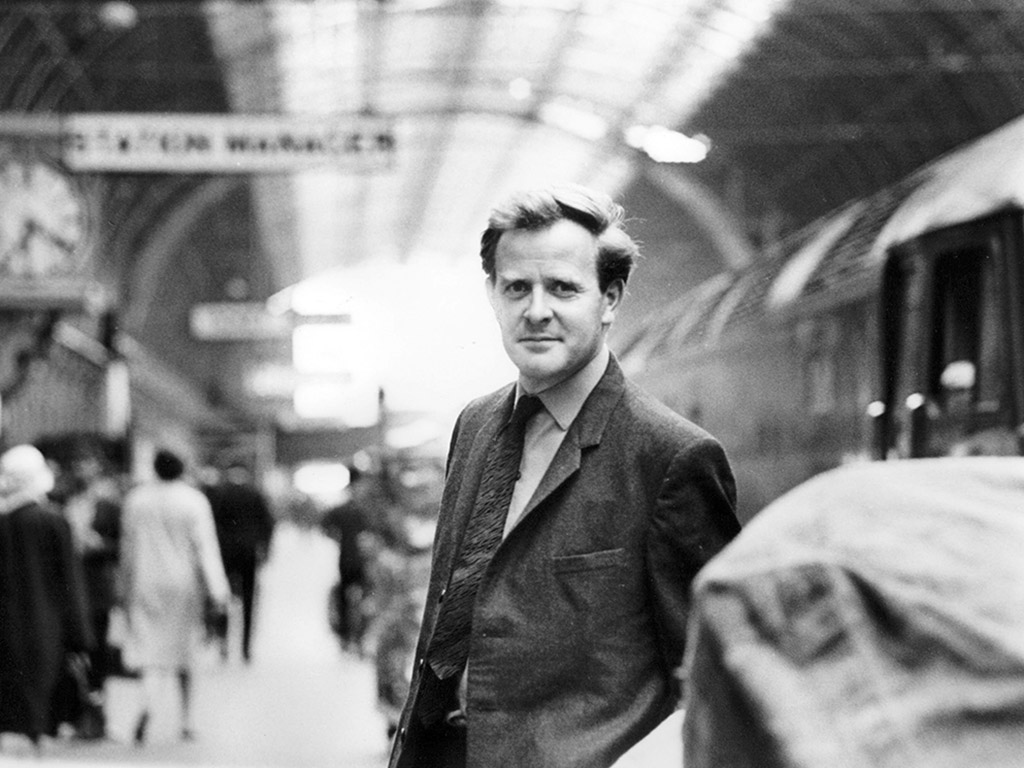

From Maida Vale, I took the Tube to Paddington. Dodgy geezers in shades, one rocking a purple and yellow coat, carried what looked like cans of lager in a plastic bag. An older guy wobbled out of a sandwich shop in an actual dirty mac, the belt dragging on the floor. I wanted to find the down-at-heel hotel where Smiley holes up to plough through dusty files (and his memory) to discover the identity of the mole. Inside, a world of old majors and obsessive landladies; outside, prematurely washed-up children, living in a van.

Today, one hotel displayed a sign in the window saying “no loitering/sitting” and particularly “no soliciting”; another was hiring a linen porter. A homeless man sat in one of the many once-grand doorways, framed by chipped and faded porch pillars. The paint has been peeling in this part of town at least since I worked around here 25 years ago. And probably since Smiley was here, 25 years before that.

Back then, it was panicky free marketeers who feared decline was unstoppable. In 1976, when Jim Callaghan’s Labour government was forced to take a loan from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the Spectator saw the IMF’s criticisms of government economic policy as right and proper. Now that sinking feeling has returned, but for different people. In January, when the IMF was critical of the performance of Britain’s economy, the Spectator denounced this as an impertinent mistake. Now it’s the Labour leader, Keir Starmer, who accuses the government of managing decline, of making Britain the “sick man of Europe once again”.

On Westbourne Terrace, I noticed a crack in a wall about 20ft long, running diagonally from top to bottom like a graph, descending from hope, via anxiety, right down into the pavement. From the 1950s, down to the 1970s; from the 1990s, down to the 2020s. Back on the Tube, an energy company advert flippantly addressed today’s cost-of-living nightmares. “In a crisis,” it smiled, “service matters.”

I headed south from Baker Street and emerged into Grosvenor Square in Mayfair. To my right was the building that was once the American embassy – now plastered in hoardings, under redevelopment by the Qatari Investment Authority. In Smiley’s day, this part of town also harboured more clandestine forms of power. First, I tried to find the grand Georgian mansion where Le Carré located a casino, which Smiley visits to look up Sam Collins, a Circus outcast with vital information. The casino bosses are “toughish boys, but very go-ahead… Like we were in the old days.” Another hint of the political power-shift to come.

I walked down South Audley Street, in the south-west corner of the square, because I wanted to see the house of another buccaneer spirit who was trying to relive the glories of the war. Lieutenant-Colonel David Stirling had founded the SAS in Cairo in 1941; in 1974 the spectre of social collapse due to strikes drove him to set up “GB75”, a volunteer force which began secretly preparing to take over worker-occupied power stations. Groups such as the National Association For Freedom (NAFF), co-founded by Ross McWhirter, found other creative ways to undermine pickets. All this was a measure of just how besieged these men felt by the power of the left and the unions. Stirling and McWhirter, co-founder of the Guinness Book of Records, knew veterans of the real Circus; in Le Carré’s fictional version, the chief admires the Argentine military dictatorship and its willingness to crush leftist politicians.

In late 1975 two restaurants, both less than 100 yards from Stirling’s house, were bombed in just over a fortnight: the Trattoria Fiori, popular with US embassy staff, and the more exclusive Scott’s. These were among the many attacks carried out by the Provisional IRA. McWhirter offered a bounty for the bombers’ capture, and a couple of weeks later he was shot dead by IRA members – some in the NAFF saw the IRA, the unions and, for that matter, the KGB as part of one vast menace.

[See also: Oxford Street’s decline is a parable for the UK]

And this was where it really hit me. Today, no one looked under any physical or economic threat at all. Scott’s is thriving. In one of the hedged-in outside booths sat a portly gent, enjoying a cigar. Back on South Audley Street there’s still a rifle shop. Further down, on Curzon Street, I passed the building that, in 1974, housed MI5. Across the road a doorman in a peaked cap and a red coat stood guard; next door there was a high-end estate agents. People passing by seemed financially at ease. Something is being managed around here, but it’s not decline – more likely asset portfolios.

Yet 50 years ago this area’s embattled citizens were on their way to recapturing economic power. Could their successors be about to lose it? A few doors down I found Smiley’s bookshop. In the window, amid titles about Elizabeth II and Evelyn Waugh, was a new book by the Financial Times’s Martin Wolf called The Crisis of Democratic Capitalism.

As evening fell, I caught a cab to Cambridge Circus in Soho, to locate Le Carré’s run-down intelligence service headquarters. The building is now home to the American fried chicken restaurant Wingstop. Compared with how this place looks in the 1979 BBC TV adaptation of Tinker Tailor, everything seemed so much more affluent. There are shops offering sushi, tech repair and flavoured vapes: teak, amber, sienna. The pavements are strewn with bin bags and bundled cardboard, but unlike in 1979, they’ll be collected before long.

Finally, I wound through Covent Garden to El Vino, the Fleet Street wine bar where Smiley meets a Circus-adjacent tabloid hack called Jerry Westerby. Contrary to what my booking app promised, it was shut – one problem Smiley never had – so I decided to come back on a weekday lunchtime, which at least would be closer to the time Smiley arrives. At the bar Smiley hears a red-faced man in a black suit predicting Britain is finished: “three months… then curtains.” Le Carré clearly had his ear to the ground.

Over lunch on Friday 29 November 1973, as government and miners squared up once more, the deputy chairman of the mining company Rio Tinto Zinc told the Labour MP Tony Benn: “We are heading for a major slump. We shall have to have direction of labour and wartime rationing.” Across town, a director of the Pearson Group was predicting a right-wing regime, complete with “tanks in the streets”. Eventually, the showdown with the miners drove William Armstrong, the great manager of decline, to his own personal collapse.

Today there were no florid, doom-mongering hacks among the wine barrels; not even any smoke. Round the table in the window, a bunch of rugby-shaped blokes – lawyers, I guess – sat having a perfectly nice time. Here at least, the ghosts of the 1970s survive only in the cartoons framed on the wall.

I walked away down Fleet Street, past the old office of the People’s Journal, and a phone box scrawled with mad graffiti about Bitcoin, elated by my magnificent city. Today’s decline and distress are far away: not on Fleet Street, or in Cambridge Circus, or Mayfair, but in other streets entirely. In the kind of place which barely ever features in John le Carré’s well-heeled, once-agonised England.

Phil Tinline is a producer with BBC Radio. His Radio 4 documentary series “Conspiracies: The Secret Knowledge” is available on BBC Sounds.

[See also: John le Carré’s acts of deception]