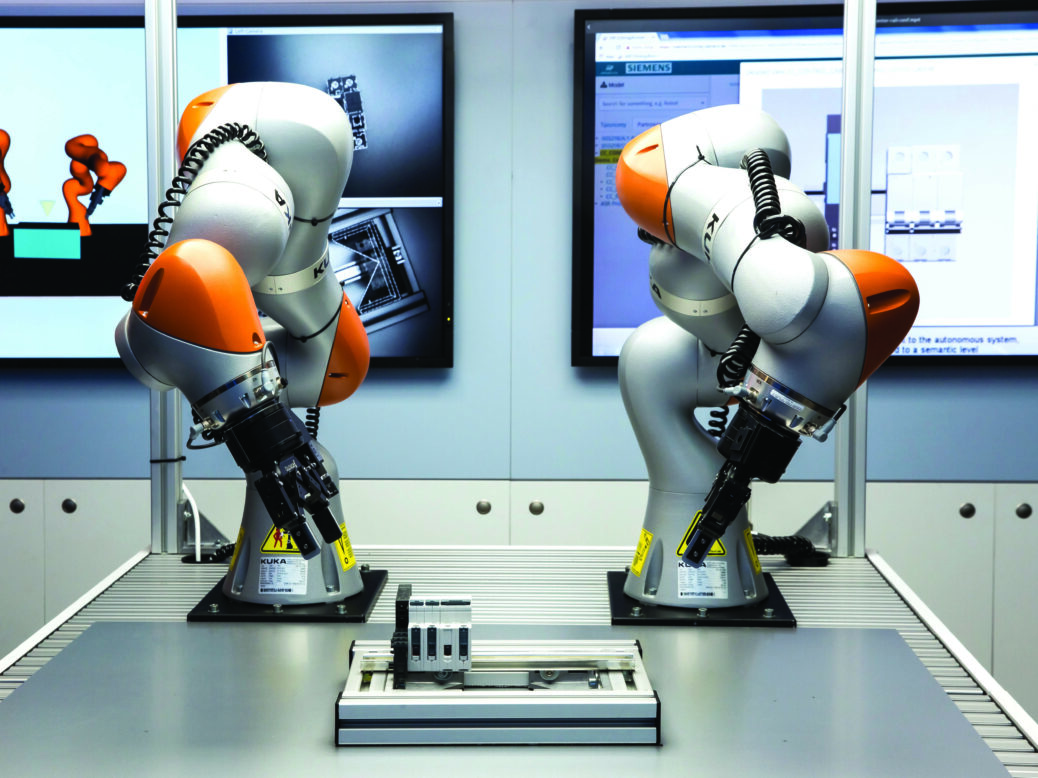

A collaborative robot, or “cobot”, is the umbrella term used to describe a machine designed to work alongside humans. Most commonly, cobots are used in the manufacturing sector as programmable arm tools to help complete the more mundane and repetitive tasks on an assembly line. More mobile than traditional robotic units, which are often static, bolted to the floor or protected by cage guards, cobots are usually smaller and can be moved around a factory. They can be mounted onto different surfaces, including the ceiling, and can be programmed to lift, push, pull, cut, open, seal and draw on different materials or objects.

“While cobots ultimately still require a human to tell them what to do,” explains Adam Kushner, chief executive of robotics distributor Robots of London, “once they have been programmed to complete a task, they are able to repeat that task over and over again, at the same pace and with very little supervision or margin for error.”

Presently, cobots are used most widely in car manufacturing. At Ford’s Fiesta factory in Cologne in Germany, cobots work side by side with 4,000 human factory workers, assisting them with fitting heavy shock absorbers to wheel arches, attaching doors and applying paint. Cobots are also being used to boost productivity in the food and drink industry, offering manufacturers a means of automating much of the preparation and packaging processes. Atria, a manufacturer of vegetarian and meat substitute food products in Finland, started using cobots made by Danish company Universal Robots (UR) last year, to speed up their production line. As the cobots could be reprogrammed, they could pack different types or different shapes of food, far more quickly than a human. Minimising production downtime is a key factor for food manufacturers and the use of cobots, according to a report from UR, meant that “packaging for different products, which usually took Atria six hours, was reduced to 20 minutes.”

Kushner’s company, Robots of London, distributes various cobot models on behalf of international robot manufacturers, and also programmes these to specification for different clients. One model, Panda by Franka Emika, is a robotic arm with nimble fingers that can be “trained by demonstration” to assemble or package small and intricate items. Kushner says: “The arm and hand can be guided to carry out a task and it ‘records’ what it’s been shown on its own hard drive, so it can do it again. The arm can work in close proximity to or in direct contact with humans, without requiring any safety measures. All of the motors and wiring are internal and unexposed. That means you don’t need caging around cobots and you save money and floor space from the start. Cobots are easy to programme and can be factory trained by existing staff, as they do not require written code, allowing full focus to remain solely on production.”

For Kushner, cobots are a “sort of phased automation”. While he acknowledges that some tasks, “at least for now”, remain beyond the capabilities of robots, he views cobots as a way of “automating what can be automated”. He adds: “Obviously a robot or cobot doesn’t have a sense of touch. So when you have an instance where something doesn’t quite slot into place perfectly, and you have to fiddle around a bit or mould something into place, then you’re going to need a human for that. But what the cobot can do is automate certain aspects of the production line, which means that you’ll need fewer humans along it, and the ones you do have will not need to do as much, because the cobot will have taken some of the preparation or heavy lifting out of the equation. It could be that the cobot does most of the work and then the human just finishes it off at the end.”

Enthusiastic about the uptake of cobots, Kushner speculates that one cobot arm on the production line could equate to “having three human staff”. He says that cobots, which typically retail at a price between £17,000 and £24,000 per unit, have a “clear advantage in that they won’t slow down over time and can work continuously”. If one human works a shift lasting eight hours, Kushner continues, “then by the fifth or sixth hour, he or she is going to get tired. The cobot, in contrast, could work solidly for three shifts in a row and wouldn’t need to take a lunch break.” The “one-off” cost of a cobot, Kushner points out, is around the same as paying one human factory floor worker’s annual salary, with the “added advantage you don’t have to worry about the cobot taking a holiday or arguing with co-workers.”

But while cobots may offset some workplace politics, the wider politics around automation persists. Are people a price that companies are prepared to pay for productivity? If a cobot can effectively substitute three people on the production line, the extent to which these machines actually collaborate with humans, appears limited. Kushner admits that the “reality of cobots will mean that a number of jobs on the factory floor are likely to be replaced”, but counters with the idea that “those people can be redistributed towards other aspects of the company”. If cost cutting is the main motivation behind cobot uptake, though, a reasonable response to that argument might be to ask why they would.

Compared to other European countries, the United Kingdom has not embraced robotics en masse. According to a report by the International Federation of Robotics, in 2017 Germany could count 309 robots per 10,000 workers. In the UK, this figure stood at 71, below the global average. Kushner, however, believes that “the tide is turning” and that UK manufacturers will soon “realise what cobots have to offer”.

And there is some evidence to suggest that his idea of redistributing workers is not a total fantasy. The Danish company Trelleborg Sealing Solutions, another client of UR, which makes adhesives for vehicles, installed 42 cobots over a period of 18 months. In that time, the company logged a reduction in costs while productivity increased. Trelleborg also reported an improvement in quality, with a far greater uniformity of product. And with increased productivity and quality, order numbers surged – to the point that 50 new jobs were created, in the company’s logistics, marketing and finance departments.

The UK’s decision to leave the European Union, meanwhile, could catalyse the use of cobots in the country’s manufacturing sector. As the terms of any potential Brexit deal are expected to reduce the access to migrant workers from the EU, Kushner says: “I can imagine that cobots will be brought in to pick up the slack.”

Automation, ultimately, is theming the future of manufacturing in the UK and elsewhere. Kushner, a champion for this change, believes that cobots can “open up the market” and “help smaller businesses upscale without having to pay lots of people”. While they will replace jobs on the factory floor, he argues, “it’s possible that cobots’ own production, engineering and maintenance will create jobs as well.” After all, he asks, “isn’t that what happened with the computer revolution anyway?”