A new report shared exclusively with the New Statesman reveals British children and young people’s experiences of Covid-19 in England.

The VOICES Project, a partnership between Newcastle University and the children’s charity Children North East, gathered insights from nearly 2,000 children aged 5-18 from primary schools, secondary schools and colleges in north-east England. Formed from thousands of in-depth interviews, questionnaires and drawings, it is the most significant chronicle to date of what it was like for children to live through the pandemic.

Participants came from a range of backgrounds, including more affluent households, the care system, pupil referral units, a religious school and youth groups; the majority live in some of the UK’s most deprived neighbourhoods. They were interviewed between October 2020 and July 2022.

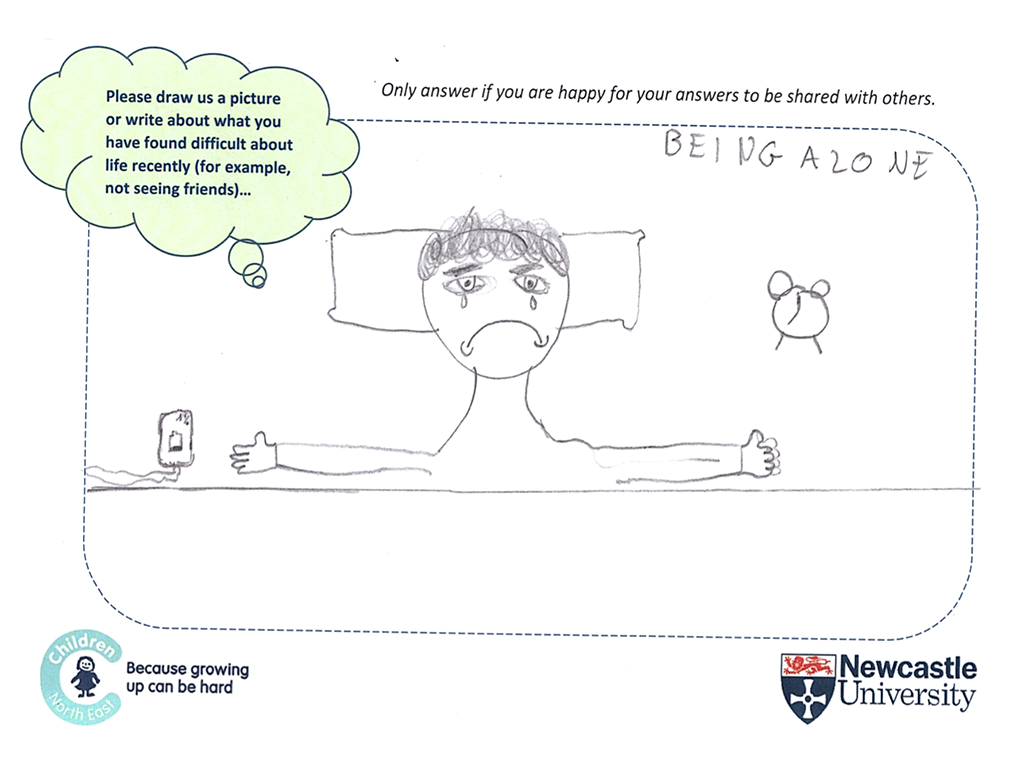

Human contact was the most important thing to children and young people, who found missing friends and family hardest during lockdowns. “I miss memories,” said one young person at a youth club. A significant number missed their grandparents, and were concerned about close family members catching Covid (“I cried worrying about if people I love were going to die”). While some appreciated more time at home (“We were forced to communicate – the family flows better now”), others felt the strain (“My parents split up over it”).

The VOICES Project focused on schools in which 35-65 per cent of students were eligible for free school meals (compared with the national average of 22.5 per cent).

“Young people have a more sophisticated understanding of inequality than we think,” said Liz Todd, professor of educational inclusion at Newcastle University and an author of the report. “Young people notice when their schools give them laptops but the government doesn’t, [and] when their mum [or] a teacher gives a personal laptop to another child at school who needs it more.”

Indeed, many saw the way the pandemic made things harder for their family, with some mentioning having less food at home, no money for the bus, or having to support their parents with family finances.

“Things are definitely loads harder for us ‘cos of Covid, my dad was off for ages with Covid,” said a Durham college student. “Him being on the sick affects how much money we’ve got, [with] just my mam going to work.”

[See also: The UK is the only G7 economy not to have recovered from the Covid crash]

Most media attention regarding Covid’s impact on children has focused on missed schooling. This subject was central to the research, with participants noting the challenges of home-learning (“Online lessons were horrible, the sound quality was terrible”), though a few enjoyed its more relaxed nature.

Returning to school also brought ambivalent feelings: relief at reuniting with friends and more teacher support mingled with unease at falling behind (“I came back and I didn’t have a clue about anything”).

The pandemic clearly had a profound impact on young people’s health. BMJ analysis of NHS data found that between April and September 2021, the number of referrals for children and young people’s mental health services was 81 per cent higher than the same period in 2019.

“I had anxiety before lockdown, but then it got really deep and was messing with my head. I couldn’t go anywhere or stay active,” said one Sunderland secondary school student. A Durham Year 6 pupil shared that he “got weird with germs” and has become compulsive about hand-washing.

Many young people said the government was not taking their mental health seriously. They felt they were often the subject of public debate – whether over schools reopening, mask-wearing or vaccinations – but their well-being was ignored. “All the government cares about is cases going down, not the damage they are doing to teens,” said a Northumberland secondary school student. “Yes, we need the cases down but we are the next generation and [they] are ruining and breaking us down. At this rate, we are not going to have a next generation.”

Among older students, the uncertainty of the pandemic period made them confused or apathetic about their futures. “[I am] feeling as though my future is very undetermined,” said a Northumberland secondary school student. “I want to be a doctor, but is it worth going to uni?”

Some children felt the government was not properly handling the crisis, or communicating the rules. “They try to make us feel bad by that ‘look them in the eyes’ advert – but they caused it. They opened up shops and had ‘Eat Out to Help Out’,” said one.

Even among the youngest in primary schools, pupils were aware of the so-called partygate scandal, saying that the then prime minister Boris Johnson “made the rules then broke them”, that “they should be demoted”, and it would “make people think that the rules aren’t important”.

“For many young people, this was the first time they had been politicised,” said Gwen Dalziel, participation team manager at Children North East. “They became more engaged with news broadcastings, and developed greater understanding of the organs and functions of government. They felt they had the right to hold politicians accountable for their actions.”

The pandemic shaped key milestones in children’s education and development, concluded Luke Bramhall, head of youth services and poverty proofing at Children North East. “It is now important that we listen to their voices and provide support that meets their unique needs.”

[See also: “We are uniquely unprotected” from our own government: Adam Wagner on the Emergency State]