I heard Cheryl and Mary say

There are two kinds of people in the world today

One or the other a person must be

The men are them, the women are we

And they agree it’s a pleasure to be

A lesbian, lesbian

Let’s be in no man’s land

Lesbian, lesbian

Any woman can be a lesbian

So sang Alix Dobkin in her 1973 song, Every Woman Can Be A Lesbian. I came out, or rather was outed, aged 15 while still at school in 1977, and favoured Marc Bolan and The Jackson Five over feminist hippies strumming guitars. It was not just folk music I felt uncomfortable with. The word “lesbian” was so steeped in negative connotation I could not bring myself to use it. Watching The Killing of Sister George with its gross characterisation of lesbians only compounded my self-hatred. There was no one to talk to, and I knew no other lesbian or gay person.

I had been outed by horrible boys at school who I refused to shag. They had noticed the rather blatant signs of my massive crush on my best friend. As I was enduring heckles of “lez be having you” and “dirty lezzer” in the school yard, my crush, who had been my best friend, was off asserting her heterosexuality with several of the boys.

I have no idea what would have happened to me had I not met David. My Saturday job was in a hair salon in my home town of Darlington, where David was a trainee. In between sweeping floors and washing heads we would tentatively size each other up. One day I said to David, “I like girls” and he said, “I like boys”, and linking arms we strolled down to the gay bar in the next town, using each other for protection.

Today I am a very happy lesbian and would recommend it for any woman. I have gone from self-doubt and loathing to sheer militancy and pride, and I have the pioneers of Gay Liberation and feminism to thank for my happy state.

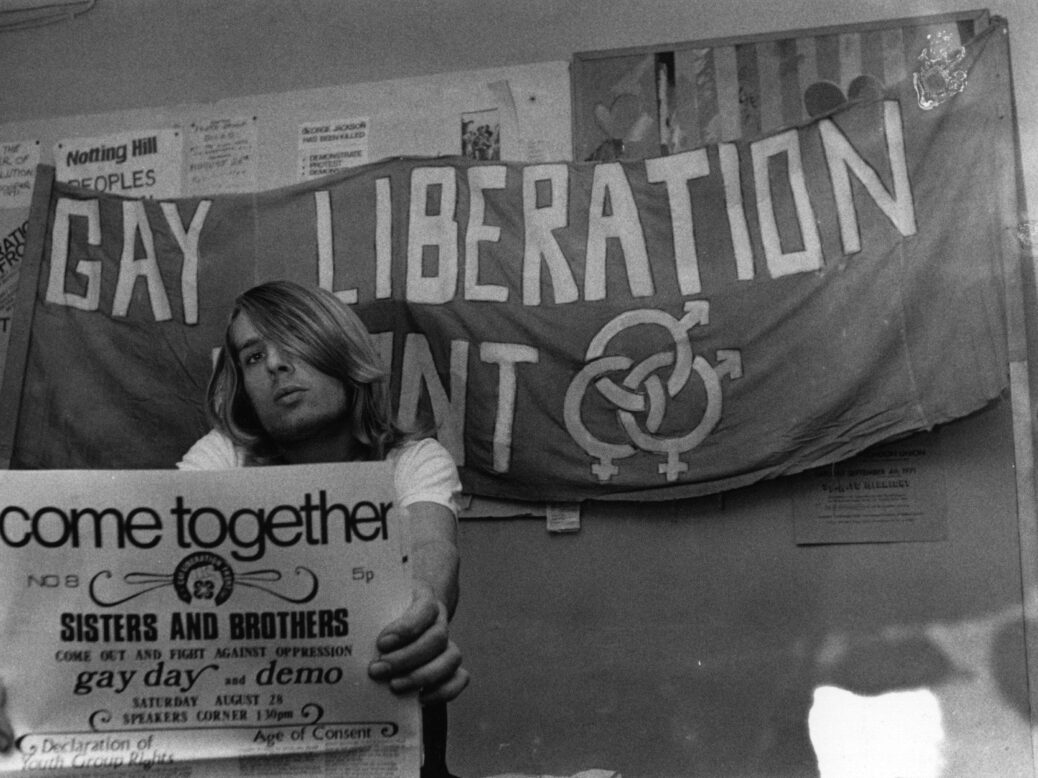

The Gay Liberation Front (GLF) was founded in 1970, and its first meeting comprised of 19 gay men and lesbians. It took its inspiration from the early days of second wave feminism, was radical and uncompromising. Its manifesto was revolutionary and uncompromising, and eschewed the accepted explanation for homosexuality, ie that same sex attraction resulted from a rogue gene:

The truth is that there are no proven systematic differences between male and female, apart from the obvious biological ones. Male and female genitals and reproductive systems are different, and so are certain other physical characteristics, but all differences of temperament, aptitudes and so on, are the result of upbringing and social pressures. They are not inborn.

The GLF fizzled out, with most of the lesbians leaving the men behind, complaining of sexism. Many of those women began to campaign for women’s liberation, which, they argued, would automatically result in women being free to escape the confines of heterosexuality.

By the time I was dancing to Ring My Bell in the gay disco with women so butch they looked like they could kick-start their own vibrators, the Gay Liberation Front’s hey day was over. But feminism was at its peak, and it was in 1979 that I met the Leeds women, all of them lesbians, all speaking about their sexuality as a benefit of women’s liberation and freedom from what Adrianne Rich named “compulsory heterosexuality”.

In 1981 the Leeds Revolutionary Feminist Group published the pamphlet: Love Your Enemy? The Debate Between Heterosexual Feminism and Political Lesbianism (LYE). “All feminists can and should be lesbians,” the group pronounced. Appealing to their heterosexual sisters, the group urged them to get rid of men “from your beds and your heads”.

The publication of LYE was the one of the first times that the notion of sexuality as a choice had been publicly raised in the UK women’s movement. Most feminists at the time believed that sexual attraction was innate and that there was no possibility of exercising choice over one’s sexual preferences.

If I had a piece of North Face clothing for every time a straight woman has said to me, “I wish I were a lesbian, but I just don’t fancy women” I would be able to open a Dyke Wear Emporium.

The Leeds feminists were not the first to pose the question about sexual preference being a liberatory choice. Indeed, they were inspired by a book by Jill Johnston, an American writer, who gained international notoriety in 1973 with the publication of her collection of essays Lesbian Nation: the Feminist Solution. Johnston argued that women should not sleep with “the enemy” (men), but should become lesbians as a revolutionary act.

I loved the sense that I had chosen my sexuality and rather than being ashamed or apologetic about it, as many women were, I could be proud, and see it as a privilege. In those days I would wear badges proclaiming “We recruit!” and “How dare you assume I am a heterosexual?”

But things have changed, and, these days we appear to have returned to the essentialist notion that we are either “born that way” or will be unthinkingly heterosexual. We have given up our choice for a medical diagnosis with no scientific basis.

When US actor Cynthia Nixon announced that she was a lesbian in 2012, having previously been in a heterosexual relationship, she proudly added, “I’ve been straight and I’ve been gay, and gay is better.” Nixon, despite being a positive role model for those in the closet, and a massive challenge to the bigots who like to assume we are full of self-loathing, was pilloried by some of the LGBT community who accused her of playing into the gay-hater’s hands. If you can “choose” to be gay, they will argue we can “choose not to be”.

I and many other lesbians do not wish to dance to the bigot’s tune. Despite the prejudice and bigotry lesbians face, even today after 45 years of gay liberation, being able to reject heterosexuality can be a positive choice under patriarchy. In the brave words of Cynthia Nixon,

“…for me, it is a choice. I understand that for many people it’s not, but for me it’s a choice, and you don’t get to define my gayness for me.”

“Straight Expectations” (Guardian Books, £12.99) by Julie Bindel is out now