David Attenborough’s claim that the world is overpopulated is his most popular comment online, a new study shows. More than the TV presenter’s documentaries, messages on single-use plastic or his calls for animal preservation, this is the topic that has consistently and dramatically provoked the most conversation on social media in 2020.

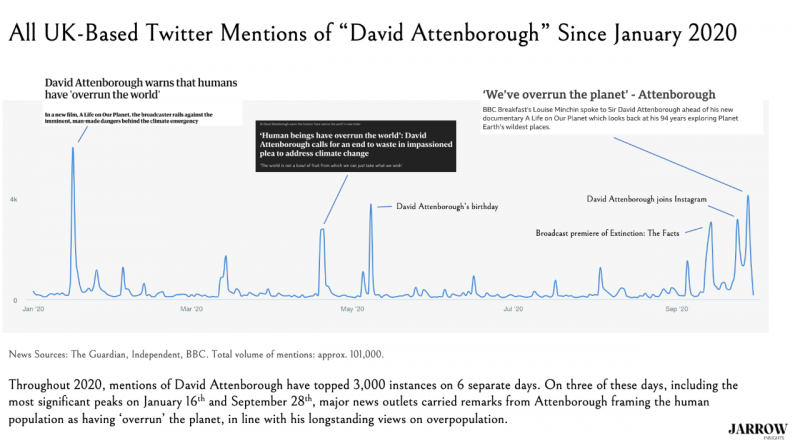

The study, carried out by Jarrow Insights, analysed posts on Twitter from 1 January 2020 through to 1 October – the latter of which was just days after the release of Attenborough’s new Netflix documentary, David Attenborough: A Life On Our Planet. The analysis found that the two largest spikes of online conversation related to Attenborough during that time period were both on his overpopulation comments, and the subject also sparked a third, only slightly smaller spike. These statements amplified overpopulation discourse online by a factor of millions. All other spikes – related to matters such as Attenborough joining Instagram, his documentaries, or his birthday – were far outweighed by these two overpopulation instances.

In reality, it is well-documented that the impact of overpopulation on climate change is much exaggerated – in fact, global population growth is slowing, despite repeated arguments that it is increasing exponentially. Concerns regarding overpopulation typically reference poorer countries where the population is growing fastest. However, the poorest half of the world contributes just 10 per cent to the planet’s consumption-based carbon emissions. Conversely, the richest 10 per cent contribute 50 per cent of global emissions, putting overpopulation far down the list of climate change contributors (Attenborough has recently acknowledged this himself, arguing that capitalist excesses in the West must be “curbed” to save the planet).

“We were surprised and disturbed to see the extent to which Attenborough’s anti-scientific claims about human overpopulation were the dominant frame within which almost all significant online conversation about him took place over the past year,” says Nolan MacGregor, the co-founder of Jarrow Insights. Crucially, he notes, most of the posts discussing Attenborough’s overpopulation claims gave tacit support to the idea, with few dissenters (of those, most promoted basic climate change denial).

“It would not have been possible to prove that [this is

his most popular idea] without a quantitative data analysis over time,” MacGregor added. “If you’d asked any of us at Jarrow, we’d have said we knew he held these views but that surely what he’s most known for, and what most people care about, is his general environmentalist stance.”

[See also: How can film narrate the climate crisis?]

The past few years have seen a large spike in climate change activism – the rise of Extinction Rebellion and the increased visibility of activists such as Greta Thunberg have pushed green issues into the mainstream. The pandemic has also accelerated climate change advocacy, with increased awareness about the impact of travel on the planet during a year when few people are flying. However, this awareness has also accelerated the popularity of hard-right splinter ideologies that aim to popularise dangerous ideals.

Ecofascism is the most popular of these theories, and is fundamentally underpinned by the idea that the planet is overrun by humans who will kill the earth unless a major intervention occurs. It pushes the ethnonationalist idea that the only remedy is to cull human life and send people back to their “racial homeland”. While this level of ideological extremity has not grown significantly since the pandemic, watered-down versions of these ideas have crept their way into the mainstream. Popular memes such as “the planet is healing” and “humans are the virus” circulated online in light of these stories when the pandemic began. Many climate change activists, on all sides of the political spectrum, argued that extreme measures must be taken to limit the population and that Covid-19 has helped achieve this aim.

[See also: Is coronavirus causing a rise in ecofascism?]

MacGregor argues that the potency of Attenborough’s overpopulation theory is cause for some concern. “Even the broadcast premiere of his latest film did not generate more conversation volumes than his overpopulation claims,” he says, emphasising how widely unchecked these claims have gone. MacGregor believes that tracking the strength of Attenborough’s argument will be crucial to understanding “the evolving nature of ecofascist mainstreaming in the information ecosystem.” And while Attenborough himself has never shown sympathy for the ecofascist movement (or cited any other typically ecofascist ideas), his advocacy of overpopulation concerns will still be seen by ecofascists as a victory. By continuing to push this particular pillar of his climate change activism, he could prove useful to ecofascists – lending a friendly face to misattribute to their much more extreme and violent cause.