In 1981, a woman was found murdered in a roadside ditch in Ohio. The police believed she had been killed just hours earlier, but it took them 37 years to discover her name. On 12 April 2018, she was formally identified as 21-year-old Marcia King. The breakthrough was made thanks to the DNA Doe Project, a non-profit organisation founded by two volunteer forensic genealogists, Colleen Fitzpatrick and Margaret Press.

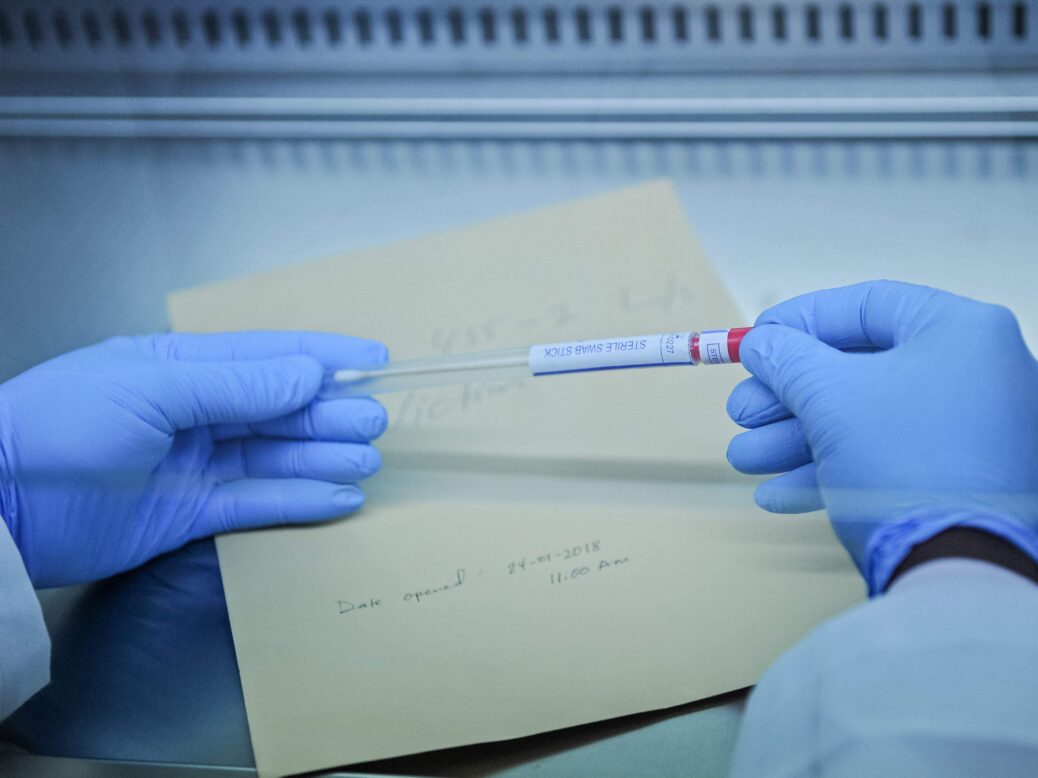

The DNA retained from King’s autopsy had degraded, but they were able to extract enough information to create a profile similar to those generated by commercial testing sites such as 23andme or Ancestry.com. They uploaded this information to GEDMatch.com, a database that allows users to share their DNA profiles and search for genealogical matches, where they identified one of King’s living relatives.