Can you ever really escape your digital identity?

Mark Farid thinks so. On Monday night, at a panel discussion of digital privacy hosted by the University of Cambridge’s Festival of Ideas, Farid handed out a stack of A4 pieces of paper to a befuddled audience. Typed out on each were his login details. All of them. All five email addresses. Facebook, LinkedIn, Skype, Amazon, Apple ID.

Even if he’d missed a password out, we’d be pretty safe in the assumption it was something to do with Leicester or The Strokes:

After a moment of shock, the audience, me included, busied ourselves on our phones. One man raised his hand to announce that he’d already logged into Farid’s Facebook page and changed the password. Within minutes, his Hotmail password was changed, too. I managed to log into LinkedIn, and wondered what to do next. Endorse someone’s skills? Send off a scattershot round of connection requests?

From this moment until next April, Farid will try to live without a digital footprint: he will use only pay as you go phones with little or no internet connectivity (“I want a flip phone”) and Oyster cards, and will create dedicated email accounts for anything he needs to do online. As far as possible, he hopes to be untrackable.

* * *

Farid and I spoke last week about a different, far less personal project, out of which the password stunt grew: Data Shadow. Data Shadow is basically a shipping container, sitting in a Cambridge garden outside the room where we’re watching Farid commit privacy kamikaze.

Visitors step inside the container, and meet one of several scenarios, depending on which parts of the technology are working. Farid’s favourite runs thus: once inside, your phone automatically connects to a wifi network, which poses as your phone provider. It pulls out your name and recently visited locations and projects them on the wall. At the same time, two more projectors beam outlines of your body on to the walls. One is filled with recent text messages; the other with your photos. “The algorithm is trained to pick up flesh tones,” Farid tells me. “We’re trying to find the most embarrassing pictures we can.”

You’re then asked to make a phone call to someone. As you do, another phone outside the container starts to ring. If a passerby picks up, they can join in on – or simly listen to – your conversation. When the door of the container shuts behind you, your data is wiped from the system, and you receive a text explaining what just happened.

The project, funded jointly by technology agency Collusion, Cambridge University, The Technology Partnership and Arts Council England, cost £30,000. Only a small portion of this was spent on the technology it takes to hack into a phone.

Before the talk, Farid and I visit the container, and he hacks into his phone and shows me his own data shadow. As the body-shaped messages and photos flicker around me, I ask Farid if he’s nervous that he’s about to hand over his online identity to the public. Almost no one knows what he’s planning – not even his housemates. “To be honest, I’ve been too stressed to be nervous,” he says. He has deleted emails containing sensitive information sent to him by others, but everything on his Facebook, for example, is still there. We’ll be able to look through his messages, friends, history, photos, and texts.

Farid tells me he’s taken out three types of insurance against whatever we, the audience, might try to do with his social media. But there’s no insurance against friends and family getting angry about the indirect access the public will have to their life too; the pictures and messages we’ll all be able to see. “No, I suppose not.”

* * *

The seed for these artworks was planted when Farid stopped getting stopped in airports. On a school trip to New York aged 15, Farid was held back at border control for over an hour. “They basically asked whether I was a terrorist – ‘do you have any firearms’, ‘do you play with explosives’.”

Over the next few years, something changed: Farid got social media. Now, he is never stopped. Part of the investigation he’s carrying out by giving up his online identity is how this will affect the state’s treatment of him – now they can no longer assume they know what he’s doing, perhaps that level of suspicion will return.

Online surveillance gives those watching the sense that they know what we’re up to. Employers may find questionable pictures or posts on your social media, but they’d be even more concerned if they couldn’t find you at all. In 2012 German newspaper Der Taggspiegel, pointed out that neither James Holmes (the murderer of 12 in a Colorado cinema) nor Anders Behring Breivik had Facebook profiles. A lack of online presence is, in a word, suspicious.

* * *

At the talk, Farid explains to the audience that big companies want us to relinquish our privacy, and that this is incredibly dangerous. “Privacy is the most important thing we have. Without it, you can’t do anything. You start to self- censor.” In the US, he tells us, the courts have ruled that the fourth Amendment – the right to privacy – does not apply to non-US citizens. The US can (and does) monitor an endless list of groups and individuals without warrants, including Angela Merkel and Amnesty International.

During the panel discussion, two examples come up which seem to outline our contradictory approach to privacy. One audience member raises something called the “chat room paradox”, which was first raised in 2007 in the early days of forums and social media: if your child enters a chat room, you want them to be totally anonymous, yet at the same time, you want to know everything about the identities of the other people in that chat room.

Then there’s the fact that discussions of privacy and state surveillance often come down to the phrase “I’ve got nothing to hide”. We assume that only criminals would want privacy from the state. Yet as Daniel Thomas, a researcher at the University of Cambridge, points out, it’s no coincidence that Germans are far more cautious about giving up their privacy than we are. “They know – they remember – that the state is willing to collect your underwear to keep in jars in case they needed to train dogs to chase you”. (Ironically, German authorities used this tactic again to track down violent protesters at 2007’s G8 summit). In a basic sense, these “odour jars” were collections of “data” used by the state to track individuals. In Soviet-run East Germany, individuals were encouraged to spy on their neighbours. If that state existed now, it wouldn’t need them to.

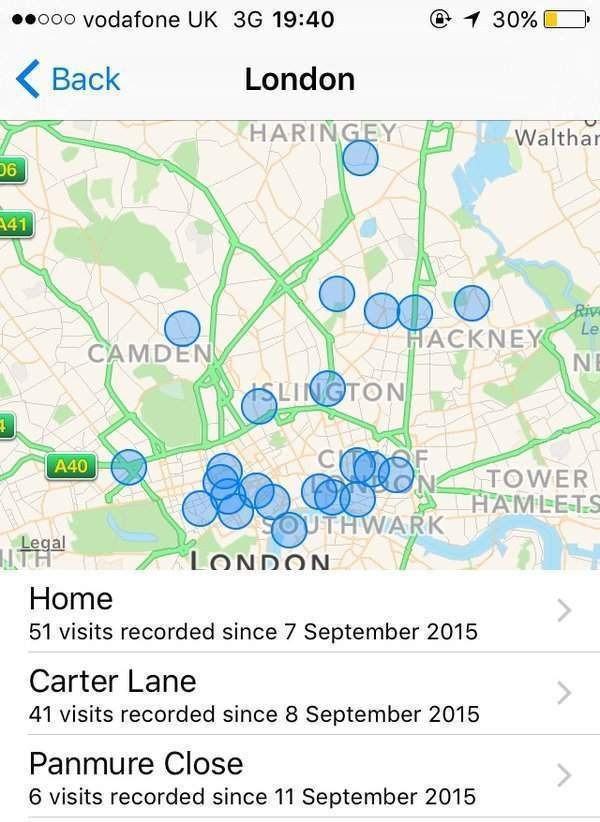

As a demonstration of this, Farid asks the audience to go onto our location settings on our iPhones or Androids, and see whether our phone has been tracking our locations. I was under the impression I’d switched my location services off, but no such luck:

(To check yours on an iPhone, go to settings – > privacy – > location services – > system services, right at the bottom of the page.)

As it stands, we give up our data in exchange for the convenience free online services and our smartphones give us. “But what happens if you subvert this situation?” Farid asks us, gathering up the stack of papers containing his passwords and preparing to hand them out. “What happens if you give it all up?”

Earlier, I asked Farid why he decided to take the project to such a personal extreme. “What we’re trying to do with Data Shadow is show that this could have been you. Your data could be mined by anyone. People need to start taking responsibility for that.”

* * *

As I walk back to Cambridge train station, I open Google Maps. “Google Maps neeeds permission to show your location on the map. Turn on location services to navigate.” I hesitate, still holding Farid’s list of passwords. Eventually, I turn it back on.

This article appears in the 28 Oct 2015 issue of the New Statesman, Israel: the Third Intifada?