A parliamentary researcher, who is well-known among China watchers, has been arrested on suspicion of spying for Beijing.

The researcher had worked closely with the security minister, Tom Tugendhat, and the chair of the Foreign Select Committee, Alicia Kearns. Both politicians are Sino-sceptics who have called for the government to recognise the threat China poses – which is likely one reason Beijing might target them.

The incident raises questions about parliamentary vetting – a long process, different to security clearance, that can take months – as well as confirming, if it was necessary, the extent of Beijing’s infiltration of British politics. That there may be Chinese spies in Westminster should come as no surprise. In July, the Intelligence and Security Committee found that Chinese state intelligence was targeting the UK “prolifically and aggressively”. Sources tell me Labour’s shadow foreign secretary David Lammy will call for a faster response from the government to the committee’s report.

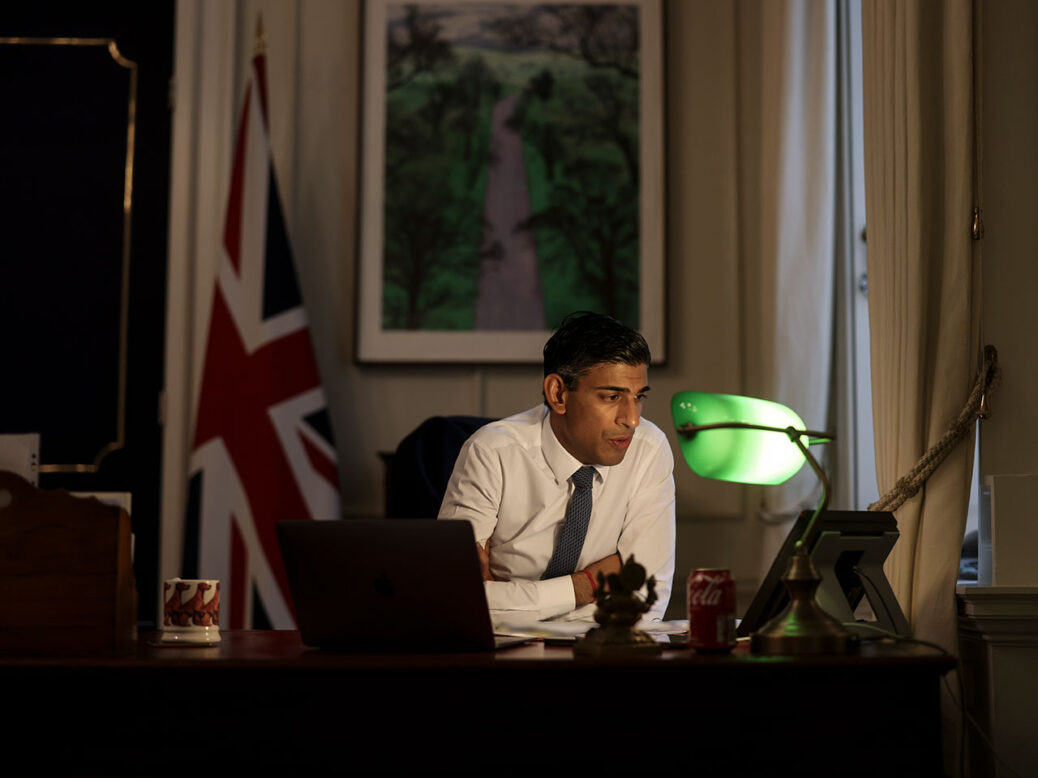

The arrest will spur on calls from Conservative backbenchers for the government to adopt a more sceptical relationship with China. Rishi Sunak raised concerns about Chinese interference in parliament with the Chinese premier, Li Qiang, at the G20 summit over the weekend. But expect an urgent question in the Commons later today.

Sunak’s foreign policy strategy since becoming Prime Minister has been the opposite of combative or isolationist. Instead he has sought to engage with the Chinese government, all part of what he calls “robust pragmatism”. Only last week, it was revealed that China will be invited to Sunak’s summit on AI in November. This came after the Foreign Secretary, James Cleverly, visited China over the summer – the first visit from a senior UK figure in five years.

Sino-scepticism in parliament reached an apogee in 2020 when the suppression of pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong was most visible, and reports about the oppression against the Uyghurs were in the news. One question is whether this episode, the arrest of alleged spies, will restart disharmony between the government and its backbenchers. At a minimum, it will make Sunak’s policy of engagement with China even harder to sell.

This piece first appeared in the Morning Call newsletter; subscribe to it on Substack here.

[See also: The week that ruined Rishi Sunak’s autumn]