The benefit cap is an austerity-era welfare policy that is still hurting families.

Announced at Conservative Party conference in October 2010 and introduced from April 2013 by the then-chancellor George Osborne, it put a limit on the total amount of benefits working-age people could claim.

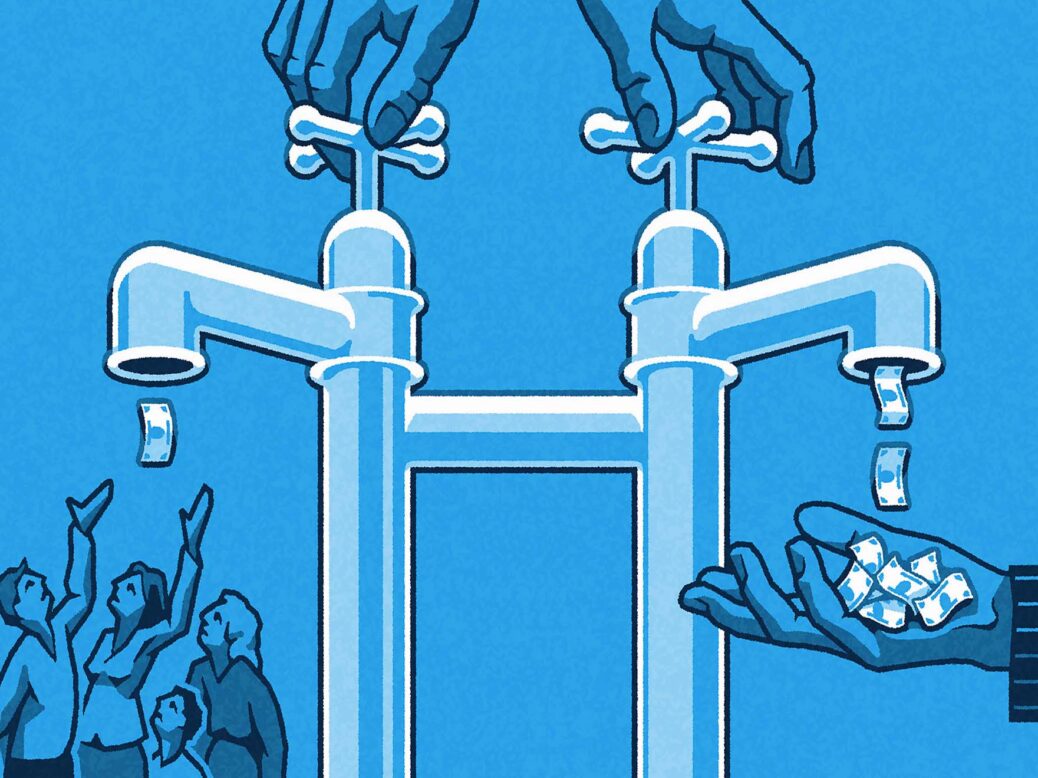

This limit was set with what Osborne described as a “very simple principle”: “Unless they have disabilities to cope with, no family should get more from living on benefits than the average family gets from going out to work. No more open-ended chequebook. A maximum limit on benefits for those out of work; set at the level that the average working family earns.”

The benefit cap started at a £26,000 limit per household in 2013 (and £18,200 for single adults with no children), and was then reduced in 2016 to £20,000 (and £13,400 for single adults with no children) and £23,000 in London (and £15,410 for single adults with no children).

[See also: Will the £20 Universal Credit cut become Boris Johnson’s government’s worst decision?]

Although it sounded tough but fair, it made little sense alongside the Conservative Party’s other major reform to the welfare system, Universal Credit, which was supposed to simplify benefits and ensure each household received what it required each month, like a salary.

“We’ve never had such a popular policy”

The benefit cap was passed off as part of the austerity agenda – whereby the coalition government began cutting budgets in its stated attempt to make up the deficit following the financial crash.

Yet David Freud, a Conservative peer who was a welfare minister at the Department for Work and Pensions at the time, recently revealed the benefit cap was really for the sake of popularity rather than saving money or sound policy.

In a new book called Clashing Agendas: Inside the Welfare Trap, published by Nine Elms Books, Freud writes of his “mounting dismay” when he heard Osborne announce the policy he said “made little sense” and “would be painful both for welfare recipients and for the Department to implement”.

[See also: Tory ministers keep repeating the same myth about Universal Credit – here’s why it’s untrue]

He claims the then-work and pensions secretary Iain Duncan Smith consoled him that “at least it sends out a signal about the limits to welfare”, and Osborne’s former chief of staff Rupert Harrison told him later: “I know it doesn’t make much in the way of savings but when we tested the policy it polled off the charts. We’ve never had such a popular policy.”

(Former colleagues of Harrison do not recognise the quote in Freud’s book and claim Harrison would never have said it. The New Statesman also understands that Freud has not discussed the quote with Harrison. Neither David Freud nor Iain Duncan Smith responded to a request for comment.)

Freud himself writes: “Some of the measures sent a very clear message about the limits to welfare, even though the savings were relatively small. The Chancellor’s Benefit Cap was the best example. It was estimated to save less than £300 million a year. However, it was designed in a way that incentivised people to enter the workforce (or, less desirably, to claim disability benefits).”

Money saved from the measure has been negligible – just £190m a year (which amounts to just 0.1 per cent of the total welfare bill, and 1 per cent of the savings expected from welfare reforms implemented since 2010). Even this is “likely to be an overestimate”, according to the Work and Pensions Select Committee.

“A benefit cap made little sense in a system designed to provide each family what it needed,” writes Freud, describing “the aggressive way that this [policy] bit on people”.

Yet it exploited the public appetite for so-called fairness, and a perceived divide between the deserving and undeserving poor.

[See also: Why cutting Universal Credit is even worse than you think]

“The benefit cap is a policy that did heavy lifting for Cameron and Osborne’s government in creating and sustaining support for harsh and often punitive welfare reforms,” said Ruth Patrick, senior lecturer in social policy at the University of York.

“The cap creates sharp, if unsustainable, distinctions between hard-working families and ‘welfare dependents’, all framed within a rubric of the need to be fair to taxpayers, depicted as subsidising the lives of those who Cameron famously caricatured ‘sitting on sofas waiting for their benefit cheques to arrive’.”

“The cap creates a sharp, if unsustainable, disctinction between hard-working families and ‘welfare dependents’”

Its popularity exposed how much had shifted in public opinion. In Margaret Thatcher’s first term, when a similar household cap was considered, it was rejected for fear of it landing badly with the electorate, according to research by Chris Grover, senior lecturer at Lancaster University’s sociology department.

The benefit cap “routinely leaves families unable to afford basic essentials for their children, with negative mental health impacts for parents”, Patrick finds in her research for the Nuffield Foundation-funded Larger Families programme.

The number of households that have had their income limited by the cap rose by more than 137 per cent during the pandemic. Almost all the capped households include children: 400,000 of them are in families in which both parents are in work.

In 2019, the Work and Pensions Select Committee found that the majority of evidence to its inquiry into the benefit cap “stressed that the ‘intolerable’ financial position the cap places families in is causing poverty and hardship”.

Ministers are currently stalling on their legal duty to review the benefit cap in each parliament. Work and Pensions minister Deborah Stedman‑Scott said in the House of Lords that the timing of the review was “yet to be determined” and refused to commit to a date.

The benefit cap’s 2016 levels remain in place today, making them even more arbitrary. They are now far below the average income (median household income was £29,900 in the financial year ending 2020).

If you earned the level of the cap (£20,000 or £23,000 in London) through work, you would be eligible for benefits to top up your funds anyway. In fact, lone parents and single-earner couples with children paying average levels of rent are still entitled to Universal Credit when their earnings reach £50,000 and beyond, according to Institute for Fiscal Studies analysis.

After 95 per cent of her Universal Credit income goes to her landlord on expensive London rent, Aurora*, a 40-year-old single mother of an eight and 12-year-old who lives in Ealing, has just £140 left over for everything else. The cap means she struggles to afford fuel and food, let alone pay other bills.

After she cared for her partner for a year before he died of cancer, and lost her temporary hospitality work, she began claiming Universal Credit in 2019. Her benefit statement currently reads “-£555”, which means, without the £23,000 cap on her household, the system has calculated that she should be due £555 more than she receives.

“The cap means I can’t afford food and fuel, making it even more difficult to find work”

“I have two young children so I’ve been searching for work particularly to fit around childcare. So it’s been really difficult to find any kind of work, and we’ve been further punished by the cap,” said Aurora, who participates in another Nuffield Foundation-funded research programme, Covid Realities.

She recently did a call centre training course but would not have been able to sign up for the overtime hours required because of her children.

“It’s been a real struggle. I’m not working and with the cap I’ve accumulated a lot of debt,” she said.

The cap is “cruel and arbitrary” in her experience, and acts as one of the “many barriers to returning to work”. Her family is living off charity donations for food, and is in rent arrears. She said they will be “made homeless soon, in all likelihood”.

And what of it simply being used as a populist device? “Well, it’s a whole kind of divide, rule and conquer, isn’t it? It’s them and us.”

Yet in the pandemic era, the public’s perceptions of welfare have been changing.

Attitudes towards the unemployed had already become more liberal before the pandemic started – and this shift continued throughout the crisis.

In 2007, just 7 per cent named benefits for the unemployed as one of their top two priorities for extra government spending. By 2018, this had risen to 15 per cent, while in the most recent British Social Attitudes survey it was chosen by nearly a quarter of respondents (24 per cent).

Charts by Polly Bindman

Prior to the pandemic, there had already been a sharp fall – from 77 per cent in 2011 to 50 per cent in 2019 – in the proportion who felt benefits for the unemployed were “too high”, and therefore discouraged people from working; rather than felt they were too low and caused hardship.

In the latest survey, for the first time since 2000, the latter view is the most popular of the two attitudes towards welfare – with just 45 per cent saying benefits are too high and disincentivise finding a job.

It may be that maintaining the benefit cap will not remain a popular policy in future.

*Name has been changed on request of anonymity. Aurora is part of the Covid Realities research programme, funded by the Nuffield Foundation, documenting life on a low income during the pandemic.