The Conservatives have a new political strategy: it’s called “lying”. They edited a video of Keir Starmer, the shadow Brexit secretary, to make it appear as if he had been stumped by a tricky line of questioning from Good Morning Britain’s Susanna Reid. But in reality he’d made an immediate reply. They’ve claimed that Jeremy Corbyn plans to extend the free movement of people not just to the workers of Europe but to the world, when the Labour leader’s attachment even to the free movement of people within the European single market is in doubt. And on 19 November, the evening of the first head-to-head TV debate between Boris Johnson and Jeremy Corbyn, the Conservatives changed their press office’s official Twitter account to make it resemble that of a neutral fact-checking service as they tweeted out pro-Tory lines.

The party’s appetite for deception is particularly unnerving because, although influence on Twitter is largely trivial as far as the struggle for political power is concerned, it’s a public platform. Most at Westminster assume that the Conservatives are engaging in even bigger fibs on Facebook or in direct mail to people’s homes – enclosed spaces where rival parties cannot easily combat untruths.

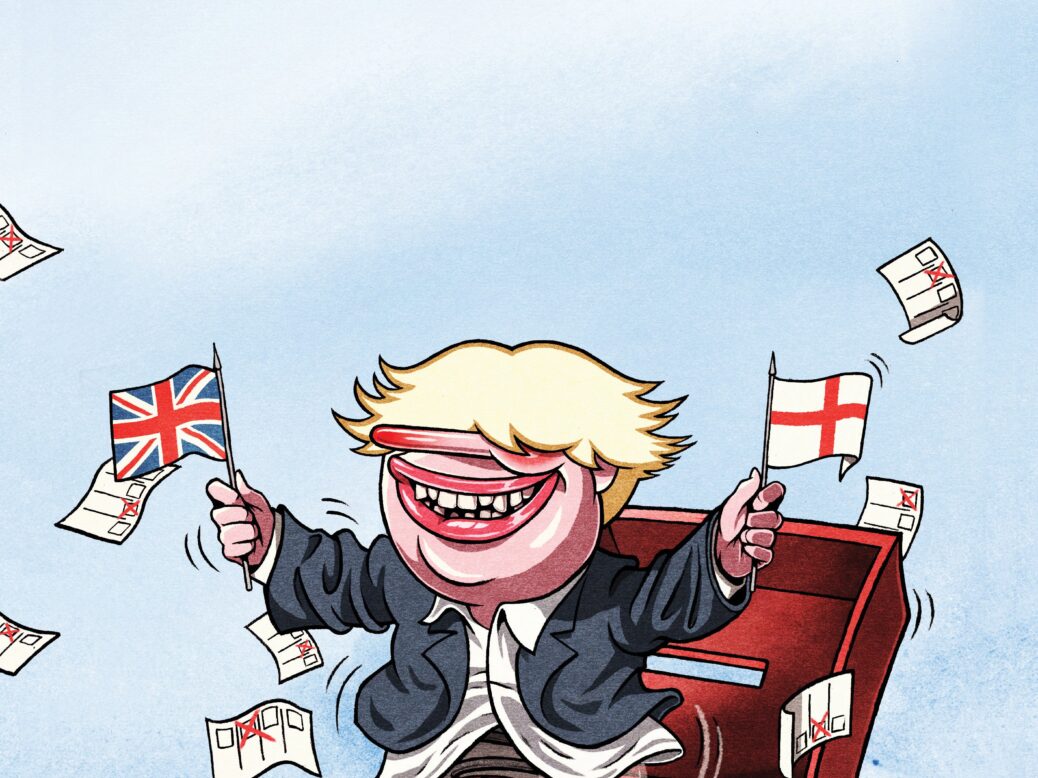

So far, these falsehoods are nothing compared to the biggest lie of all, one being repeated endlessly and in public: the party’s promise to “get Brexit done” by passing Boris Johnson’s Brexit deal into law. This is a ruse designed to con an electorate wearied by three years of talking about the European Union into voting for three decades of more of the same.

But the reason why those working at Conservative campaign headquarters are relaxed about their appetite for deception is that they think they are winning: Boris Johnson is established, according to the polls, as being more trusted than Jeremy Corbyn or Jo Swinson, while the idea that Johnson’s deal is the only way to resolve Brexit has also taken hold. As a result, there is very little the Conservatives can say or do that won’t be believed by enough voters to secure a majority on 12 December.

For the Liberal Democrats, the mood at the top of the party is far from as bleak as it was during the last general election, when their leader Tim Farron’s inability to answer questions about his views on homosexuality and abortion hamstrung the campaign. At one point, this caused the party’s internal polling to drop to a point where they feared the campaign would end with no Lib Dem MPs at all. The party still expects to end the election with more MPs than in 2017 and in all probability to have more than the 20 it held by the end of the parliament, following a number of defections.

But the success of Johnson and Corbyn in squeezing the Lib Dems out of the main television debates, and with it the headlines, means that their poll share is not rising, and that every interview they have is derailed by questions over which of Johnson or Corbyn they would put in Downing Street in a hung parliament. There is no answer that doesn’t complicate the Lib Dems’ hopes of gaining more seats: get too close to Johnson and it slows the poaching of Labour votes, get too close to Corbyn and they cannot win Conservative seats.

But at least the Liberal Democrats expect to gain seats. For Labour the picture is more troubling. At around this point in the last election, the party’s opinion poll rating had begun to climb upwards, and in parts of the country activists were beginning to detect signs not only of resilience, but of advance. Similar green shoots have yet to appear this time. The stakes are high because the party’s campaign strategy presupposes that Corbyn will trigger a change in the political weather, which means that organisers have done most of their best work in Conservative-held seats. If the national mood doesn’t shift, the lack of support from the centre may mean that Labour does worse than the polls suggest it should.

The Labour leadership has long hoped that this would be the week when the tide turned. One Corbynite referred to it as “bazooka week”, with the first TV debate (Corbyn is a more adept debater than Johnson) and the launch of the manifesto – a document well stocked with radical proposals. But Corbyn’s hopes of a decisive victory in the debate were frustrated by a format that allowed precious little direct interaction between him and Johnson. The result was a near-unwatchable draw. An immediate YouGov poll of viewers ended in a statistical tie, with 51 per cent saying Johnson had performed best and 49 per cent handing the contest to Corbyn. Most viewers were willing to say that both men had performed fairly well: an endorsement of Corbyn’s abilities, but not the emphatic victory his supporters craved.

That leaves Labour’s manifesto as its best hope of transforming its fortunes. To prevent the Tories from winning a majority, Corbyn needs to rally the majority of Remain voters to his banner. The Labour leader is not going to come out as an unequivocal advocate of Remain, in any circumstances, and would not be believed if he did. If he can rebuild his 2017 coalition, it will be through radical policies on the other issues of concern to Remain voters: the fight against climate change and for the free movement of people – both policies where he must match or exceed the offer from the Liberal Democrats and Greens.

As far as climate is concerned, that mission has been accomplished, thanks to an ambitious target of zero carbon emissions by 2030. But on migration, Labour has stopped short of the unconditional support for free movement preferred by its pro-Remain opponents. That failure might yet ratify the Conservative belief that this election is theirs for the taking – no matter how many lies they tell.

This article appears in the 20 Nov 2019 issue of the New Statesman, They think it’s all over