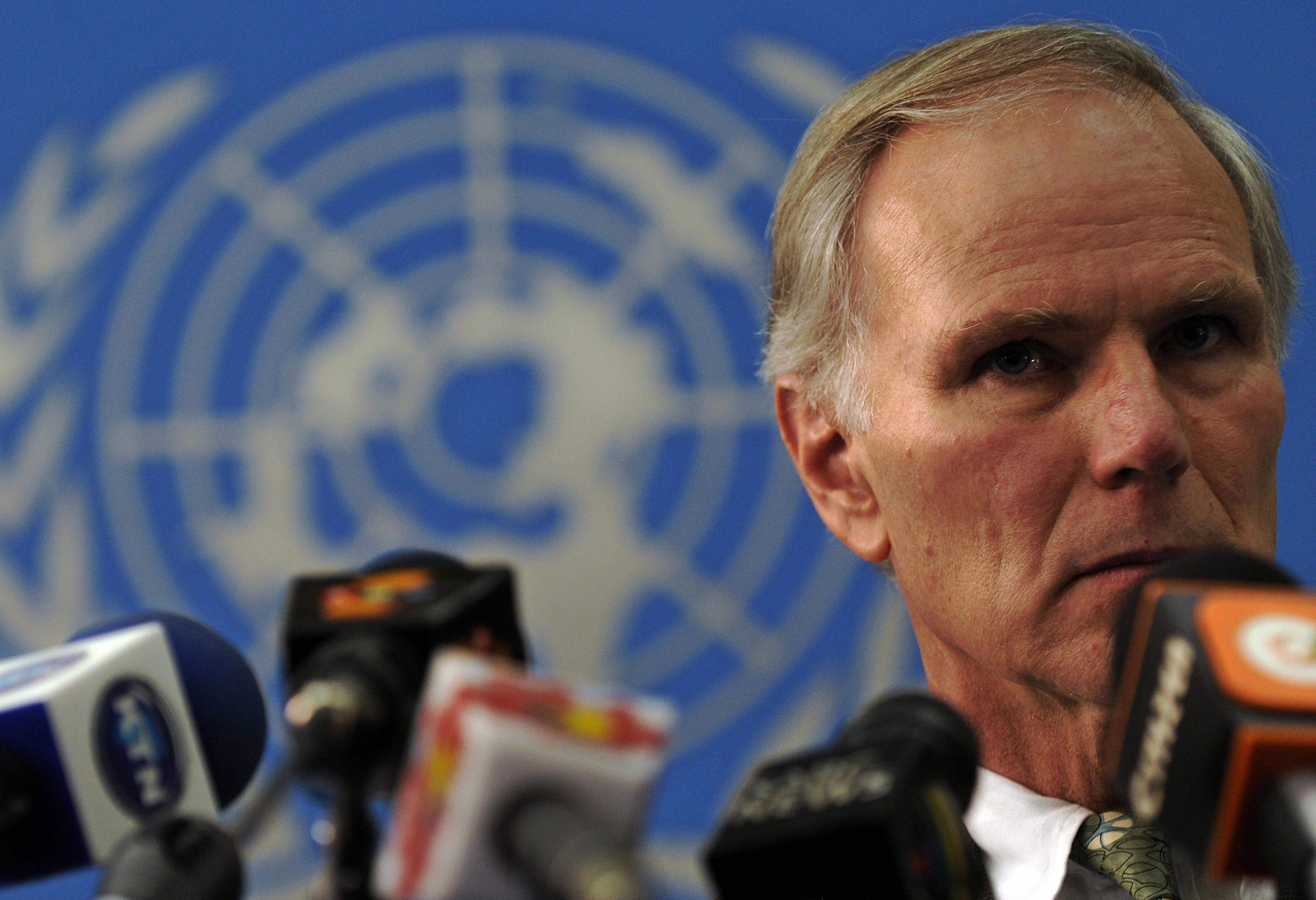

When Philip Alston, the UN special rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights, last visited the UK, he was rebuked by the Conservative Party for his excoriating report on the effects of austerity. It was, in the words of the government, a “completely inaccurate picture of our approach to tackling poverty”, and a “barely believable documentation of Britain”.

Alston, a 69-year-old Australian international law scholar, said he first thought the government’s public comment was a spoof. He may hope that his most recent report, which examines the effects of climate change on people living in poverty, is taken more seriously. The report, which Alston is due to present today at the UN Human Rights Council in Geneva, found that the world is increasingly at risk of “climate apartheid”. On the current trajectory, climate change will undermine basic human rights to life, food, water and housing. It also poses grave risks to democracy and the rule of law.

Environmental breakdown is the foundation on which the politics of this century will be built. What is perhaps most terrifying, as the journalist Kate Aronoff has observed, isn’t hurricanes or heat waves, but the ways that societies choose to deal with and prepare for these conditions. As Alston details in his report, environmental breakdown will likely deepen existing inequalities: the wealthy will pay to escape heat, hunger and conflict, and the poor will be left to suffer.

“Look at the gilets jaunes… or [Doug] Ford in Ontario, [Jair] Bolsonaro and others…. given that democracies have so far shown themselves to be pretty ill-equipped to come up with responses to climate change, there’s going to be pressures towards authoritarian solutions,” Alston tells me.

The right’s approach to the crisis has long been one of climate “scepticism”. Yet a wave of green movements, such as the youth strike for climate and Extinction Rebellion, as well as the surge in support for green parties in the recent European elections, have forced right-wing parties to eschew denial in favour of environmental policies with a nationalist slant.

Marine Le Pen, for example, recently announced a slate of climate policies with nativist overtones. Someone “who is rooted in their home is an ecologist” – whereas those who are “nomadic … do not care about the environment; they have no homeland,” she said when announcing her European election manifesto in April.

“The major public relations campaign that corporate interests launched in the United States has succeeded in turning climate change into an important part of the culture wars,” Alston tells me. Rather than addressing the reality of a warming planet, “conservatives are able to pursue their own naked, self economic interest”.

In the UK, there’s a striking difference in attitudes towards climate change among Conservative members who support Boris Johnson and those who support Jeremy Hunt, according to recent polling by YouGov. Just over one in ten Hunt supporters would like to see less emphasis on climate change — and this rises to one in four among supporters of Johnson.

“It’s become very fashionable for populists and conservatives generally to vent their anger at climate change as a phantom that is not real,” Alston says.

Johnson’s own record on green issues is mixed. He previously disavowed climate science, writing in 2015 that the theory that warm weather is “somehow caused by humanity” is “without foundation”. Professor David King, the former chief scientific adviser to the UK government, criticised the Tory leadership frontrunner for presiding over “devastating” cuts to 60 per cent of the UK’s global climate attaches during his time as foreign secretary.

Johnson since appears to have moved on the issue — in April he said Extinction Rebellion were “right to sound the alarm about all matter of man-made pollution”. But he also suggested that activists instead focus their energies on China’s emissions — ignoring the contribution the UK’s industrialisation made to global greenhouse gases. And both Johnson and Hunt have received campaign donations from the company of a prominent climate change sceptic, to the tune of £25,000 each.

When I put this record to Alston, he says it sounds “extremely familiar to those of us from Australia or the US — or elsewhere in Brazil and other countries”.

“This is a playbook that has simply been borrowed from conservatives and a range of other countries. They are all singing a very similar song and tragically it’s going down well with people who are keen not to spend money, not to change the status quo,” he adds.

The argument that it’s too expensive to properly address climate change has won the endorsement of Philip Hammond. In a recent letter to Theresa May, the Chancellor warned that achieving net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 would cost upwards of £1trn — “meaning less money available for other areas of public spending” — and would lead to industries becoming “economically uncompetitive” without government subsidies

“Let Philip Hammond roll out some serious economists to support his position,” Alston replies. “All of the leading ones that I have read would say the exact opposite — that climate change is too expensive for us not to take urgent action.

“When you look at melting poles, rising sea levels, the amount of land that’s going to be taken away, the number of people who are going to be forced to migrate — all of those are huge costs,” Alston says.

His report finds that, in the absence of radical change, the climate crisis will devastate the global economy. Two degrees of warming would cost the world $69trn (£54trn) and 13 per cent of global GDP would be lost — a scale of economic damage that is difficult to conceive.

“Climate change is the classic issue where you’ve got big corporate money lined up in the opposite direction, you’ve got a range of political parties that are dependent on money from these sources, and so popular mobilisation seems to be the principal way forward,” Alston says.

International climate treaties such as the 2015 Paris agreement have done little to help. “These are potentially important breakthroughs but all of them are subject to almost instant backtracking as soon as it gets back to the domestic level.

“Very quickly it all dissipates. That’s where public pressure comes in.”