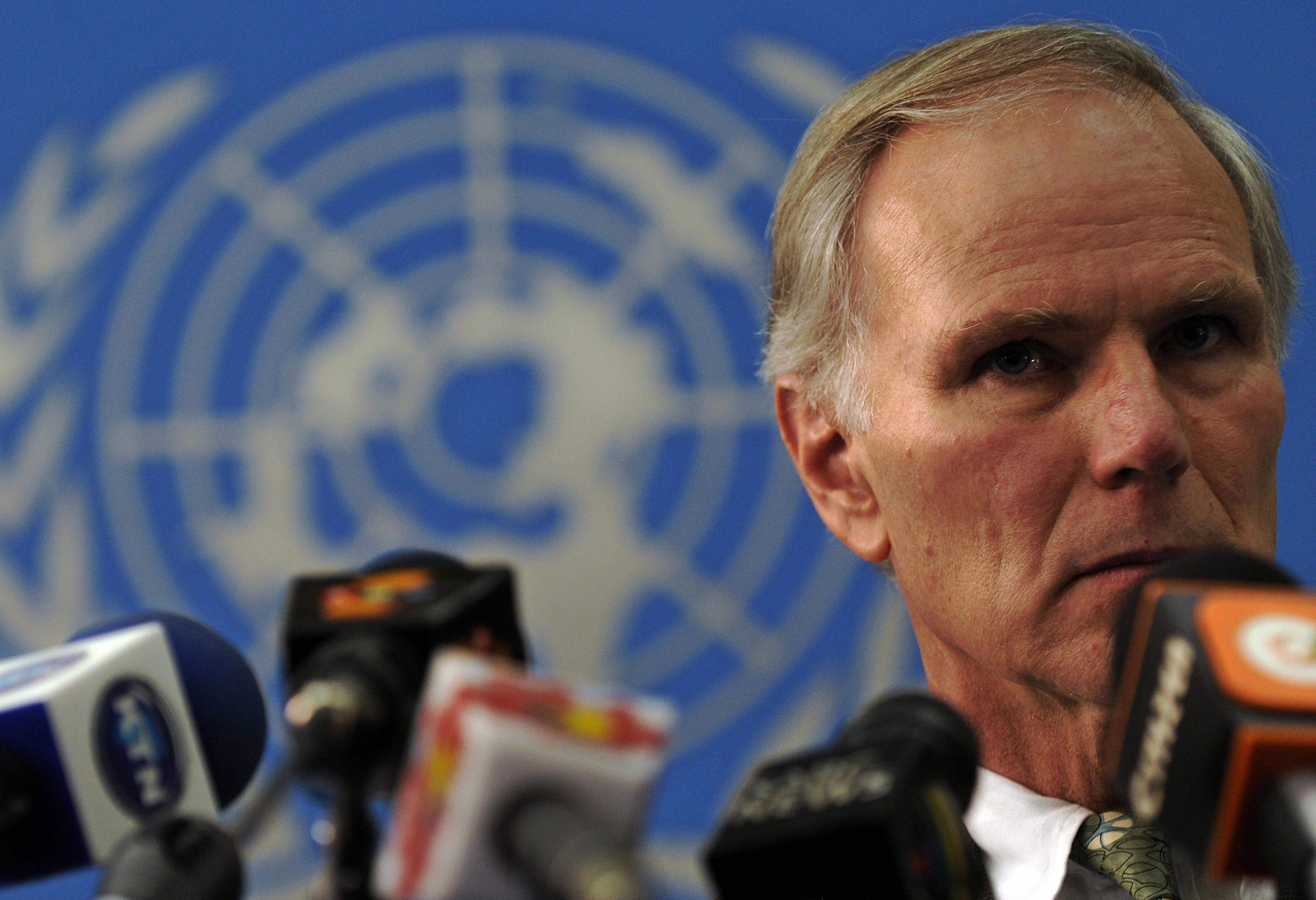

Philip Alston, a white-haired, 68-year-old in an unremarkable suit, does not resemble a traditional anti-austerity activist. But on the morning of 16 November, in a bland conference room at the United Nations’ International Maritime Organisation building in central London, he gave a withering indictment of the government’s public spending cuts. He is a law professor and has served as the UN’s special rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights since 2014. His fact-finding mission to Britain exposed the baleful effects of austerity. During his 12-day trip, Alston witnessed rural poverty in Bristol, food banks in Newcastle and hungry schoolchildren in the north-east of Glasgow.

As a sarcastic Australian – “it’s a real perfect way to punish families” was a characteristic put-down of the UK’s two-child benefit limit – Alston fixed the journalists awaiting his findings with a cynical, and often angry, blue-eyed stare as he concluded that austerity had inflicted “great misery” on people.

Alston found elements of the new Universal Credit welfare system “problematic”, “harsh” and “unnecessary” – reserving particular ire for benefit sanctions (imposed immediately for minor misdemeanours). “Sanctions have been put to me [as] cruel and inhuman,” he said. “It’s very hard to disagree.”

He described the disproportionate impact of austerity on women as “remarkable” – single mothers lose the most from the introduction of Universal Credit, some by as much as £2,000 a year. “If you got a group of misogynists in a room and said, ‘how can we make this system work for men and not for women?’ they would not have come up with too many ideas that are not already in place,” he said.

Having spoken to government officials and as many as 40 MPs from all parties, Alston reported that ministers were “in a state of denial” over the impact of spending cuts and welfare reforms he deemed “ideological”. Worse, he said the government “must be getting the message” – poverty afflicts a fifth of the population – but is “not heeding it”.

When we spoke after his presentation, Alston said that one of his “most shocking” discoveries in Britain was of “people who live in complete isolation and who are struggling to work out where their next day’s bread is going to come from – and I mean bread.”

He had heard stories of teachers smuggling clothes into school for poor children: “Here, Freddie, or Mohammad, take this shirt, take this sweater, you can use it, don’t tell anyone I gave it to you,” was how he put it. At one meeting in Newham, which has London’s second-highest poverty rate, a mother told Alston of a 20-hour wait outside social services when, having fled an abusive partner, she became so hungry she was forced to drink her baby’s milk.

“The special rapporteur listened attentively to testimony after testimony of those living in poverty,” Imogen Richmond-Bishop of the social justice charity Just Fair, one of the Newham event organisers, told me. “People shared their experiences of the shame, the fear, and the lack of security that comes from not having enough money to be able to afford to put food on your table or a roof over your head… Living proof that recent tax and welfare reforms are incompatible with the UK’s international human rights obligations.”

Having recently investigated Ghana, Mauritania and the US, Alston stopped short of comparing Britain’s situation to those countries. But he found that the government’s policies breach human rights obligations and deemed them unacceptable in the world’s fifth-largest economy.

“There are quite a number of [UN human rights] provisions that I think are not at all satisfied by existing British policies,” he said.

In April we introduced our “Crumbling Britain” series to report on the effects of austerity and the degradation of the public realm. Alston’s findings chimed with our own; he cited the disappearance of sports centres, recreation spaces, public land, libraries and youth clubs. “Damage is being done to the fabric of British society, to the sense of community… soon there will be nowhere for people in the lower-income groups to go.”

Alston sardonically added: “It’s perfect because those in higher-income groups will have more money, because their tax has been cut, but they will find themselves living in an increasingly hostile and unwelcoming society, because the community roots are being systematically broken.” Private affluence, as the economist JK Galbraith identified, coexists with public squalor.

When I pressed him on this point, Alston told me he envisages the UK “heading towards an alienated society, and one which won’t look like what Britain thinks it wants to look like”, where “pretty dramatic differences” between rich and poor will become unsustainable.

Although the government invited Alston to investigate, it complacently dismissed his conclusions, stating that it “completely disagreed” with his analysis. Amber Rudd, the new Work and Pensions Secretary, condemned the “extraordinarily political” language of his 24-page report. The Brexit minister Kwasi Kwarteng, an Old Etonian, shook his head: “I don’t know who this UN man is.”

Will it take a change of government to reverse the effects of prolonged austerity? “I think a lot of it now is gratuitous because the Tories have succeeded in changing a lot of the system,” Alston said. “I think a lot of their values are fairly mainstream now, even people on benefits would say ‘one thing I can’t stand are…’ – whatever the word you use in the UK – skivers, or scroungers, or scammers or whatever. So the harshness, as I see it, is reasonably gratuitous now. It’s just not needed.”

Theresa May and Philip Hammond have insisted the age of austerity is nearing its end. But when the government continues to deny the cost of its cuts, it feels to many like merely the beginning.

Read more of our “Crumbling Britain” series

This article appears in the 21 Nov 2018 issue of the New Statesman, The real Brexit crisis