In the past five years, a swarm of documentaries about migrants has flooded our television screens, invading our living rooms and taking over our evenings.

It’s time someone said something. We’re all thinking it.

Whether it’s a reality set-up mixing cultures, a spotlight on a town with a big first, second or later-generation immigrant community, or charting the arrival of recent refugees in an unfamiliar location, the entertainment value of British multiculturalism has not been lost on TV producers.

In recent times, they have often favoured the “social experiment” format to highlight – and sometimes attempt to bridge – cultural divides. The more gimmicky the format, the more complaints and debates these shows invite. But they divide opinion among media commentators, immigration experts and people from the backgrounds or areas explored. Where some see reductive and even incendiary pieces of entertainment, others see a rare human side to a story so often dehumanised in the mainstream media.

Stunty documentaries about British Muslims are the latest iteration of the genre. Remember Channel 4’s My Week as a Muslim last October – in which a white woman was dressed up and brownfaced to experience life as “a Muslim”? It received complaints from viewers before it was even aired, according to Ofcom.

My Week as a Muslim. Photo: Channel 4

“I for one am exhausted from other people telling the stories of Muslim women – whether it’s Muslim men or non-Muslim women,” wrote the journalist and producer Farah Jassat for the New Statesman at the time. “Muslim women don’t need intermediaries validating their experiences for them.”

What about Muslims Like Us earlier that year? Dubbed “Muslim Big Brother”, the BBC Two show last January saw ten very different British Muslims move into a house together, and was criticised for reducing Islam to a reality show, with some commentators, like the playwright Alia Bano, seeing it as a reductive tick-list of stereotypes. “Muslims Like Us didn’t quite feel like dynamite viewing – more like a roll call of the 10 usual stereotypes… You could almost see the producer ticking off each controversy from a list,” she wrote in the Guardian.

Muslims Like Us. Photo: BBC Two

These came along years after Make Bradford British, the pioneering televised social experiment in British multiculturalism, by Love Productions – the company behind the incendiary poverty safari of Benefits Street – which invited eight Bradford residents who failed the UK citizenship test to live together in 2012.

The Telegraph’s then showbiz editor, Anita Singh, condemned the programme for pigeonholing her hometown: “Bradford is the lazy TV executive’s go-to destination for racial disharmony,” she wrote.

The west Yorkshire city has received more than its fair share of visiting camera crews, mostly pursuing stories of racial tension and poverty: Bradford: City of Dreams (BBC), Breaking out of Bradford (BBC), and the dramas White Girl (BBC), Britz (Channel 4), The Last White Kids (Channel 4), Edge of the City (Channel 4), Last Orders (BBC), and Bradford Riots (Channel 4).

“It seems that every time a TV crew want to depict racial violence in Britain they flock en masse to Bradford,” said then-leader of the Labour group on Bradford Council Ian Greenwood in 2007.

The abortive Immigration Street (a programme sharing Benefits Street’s format), came along a year later, and was cut short from six episodes to one, due to Southampton locals protesting against filming.

At a public meeting of residents of Derby Road, where the programme was set, the creative director of the company behind the show, Love Productions, was booed and heckled, and warned by one local: “Do you realise the stigma that you are bringing on a community? For you it’s a six to eight weeks project; for us it will go on for a generation. Do you appreciate that?”

Derby Road sends a message to love productions and channel 4 #immigrationstreet pic.twitter.com/63s3RACrma

— Christopher Hammond (@Christophammond) July 22, 2014

The MP for Southampton Test, Alan Whitehead, surveyed the street’s residents ahead of filming, and found 95 per cent of them opposed it. He tried to stop the show going ahead, due to, “just how angry and disturbed residents were that a programme maker would descend from London and declare their street to be ‘immigration street’ when the overwhelming majority of people on the road are British citizens”.

Whitehead found the final product “didn’t bear any resemblance to the real concerns” of the community, and cautioned against this kind of TV commissioning: “I hope at very least this whole experience serves to inform makers of similar future programmes that proper communication with the community is necessary to secure a fair and balanced portrayal of that community.”

***

It’s hardly surprising this genre has taken hold, given the sexiness of the subject.

British politicians have always been obsessed with talking about immigration (they even say “we need to talk about immigration” all the time, as if it’s not something they discuss constantly). Brexit will bring a whole new border system when free movement comes to an end. And Islamophobic hate crimes had increased fivefold last June in the aftermath of the London Bridge attacks, when there was also a terrorist attack on Finsbury Park mosque in north London.

So take these tensions, add human stories and corners of the country under-explored by mainstream media, and you get the perfect televisual topic – particularly if you use a Big Brother set-up or a Wife Swap-style fish-out-of-water switcheroo.

“These programmes are a very interesting concept, because they occupy this space between news and comment and entertainment,” says Rob McNeil, the deputy director of the Migration Observatory at the University of Oxford. “To create entertainment, especially if it’s this kind of info-tainment, you need a little bit of conflict and tension.”

McNeil, who co-authored “Media reporting of migrants and migration” of the International Organisation for Migration’s 2018 World Migration Report, defends some of these programmes for giving immigration a human face.

“One thing they can do, which is positive, is to counter the dehumanising version of things,” he says. “The concept of migrants as a number can be positively countered by this idea that you bring the reality of human lives into people’s sitting rooms, so they don’t necessarily see these things purely as a statistical question.”

But audience – as well as locals’ – responses to these programmes suggest they’re doing more to perpetuate prejudice than enlighten.

Their premise is often based on popular perceptions – Bradford is no longer “British”, Muslims aren’t “like us” – which they then attempt to explore. This often falls into the trap of simply amplifying the mistaken preconception. A good example of this was the BBC’s Apprentice-does-border control documentary of 2014 Nick and Margaret: Too Many Immigrants?.

Nick and Margaret: Too Many Immigrants? Photo: BBC One

By pairing up five Brits who were anti-immigration with five immigrants, and asking the former to decide whether their new associate was a “drain” or “gain” for the UK at the end of the “experiment”, this manipulative show simply allowed people with prejudiced views to pass judgement on fellow British citizens who happened to be from an immigrant background.

This wasn’t revelatory. It was simply how things are – and shouldn’t be.

“These things do tend to simply reinforce existing narratives where they are set up in a way that suggests that they are giving one an amazing insight into something new and different,” says McNeil.

“What really matters here is that what we’re not necessarily seeing in a lot of these stories is a counter to existing narratives. It’s something that’s built on, and continuing to sell, an existing story of what migration means in a country, and how media is mediating that reality.”

***

It’s not even just the gimmicky formats that have a misleading effect. More straightforward documentaries have sparked outrage, like BBC Panorama’s White Fright: Divided Britain in January, which revisited Blackburn ten years on from its original programme of the same title to track the Lancashire town’s integration.

Focusing as it did originally on two cab drivers – one Asian and one white – and their journeys through predominantly Asian and white areas, the documentary claimed to find a town “even more divided” a decade on, which dismayed some residents.

After the programme aired, the Bishop of Blackburn Julian Henderson invited Panorama back to “tell the full story of what is happening here”, highlighting the interfaith work that goes on in the town.

“I’m very disappointed with the programme; once again we’ve had people coming to our town telling us that we have a problem,” the leader of Blackburn and Darwen Council Mohammed Khan told local news outlet The Shuttle. “They were clearly not interested in showing any of the many opportunities people have to mix or to get a deep understanding of our town and the massive improvements.”

When BBC Panorama revisited Slough last March, again after a decade, in Life in Immigration Town, it was similarly condemned by local politicians from all sides in the Slough Express.

“The BBC behaves as if it has a licence to sneer at Slough, with The Office, Making Slough Happy and now this programme,” said Labour MP Fiona Mactaggart. “We have had enough.”

“It was lazy, clickbait journalism that took a superficial look at the complex issues of immigration in order to provoke outrage,” said the deputy leader of the Conservative group on the council, Rayman Bains. “Did we learn anything new about immigration and did the programme add to the debate in a constructive way? No.”

However, when the Cambridgeshire town of Wisbech hosted the BBC in 2010, in The Day the Immigrants Left, its then-MP Malcolm Moss condemned the show for opposite reasons – for giving an overly positive picture of migration’s effect on the area. “The implications on the local community were far greater than that displayed,” he said at the time. “It was a jaundiced and false view.”

The problem for television producers is that they tend to display one area as representative. But even if the place in itself is interesting, it may not give a broader view.

“[They] are not always entirely upfront, in that they tell us a story about how things are by choosing very particular examples quite often,” says the Migration Observatory’s McNeil. “And those very particular examples are not necessarily entirely based on the whole picture.”

This can happen with people as well as places. For example, Channel 4’s 2017 three-part series Extremely British Muslims dedicates an entire episode to following a white Muslim convert whose brother was involved in the English Defence League, and one of a tiny minority of British Muslim women who choose to wear a niqab. Absorbing human stories, but not representative at all for a show promising an “eye-opening view of British Muslim life”.

Extremely British Muslims. Photo: Channel 4

“One of the things that determines whether or not these kinds of programmes work are whether or not people actually end up having the human engagement they would have without the cameras,” says Sunder Katwala, the director of the thinktank British Future.

“That’s what I thought was interesting about Make Bradford British,” he says, having written positively about the programme at the time. “What feels like a very artificial setting turns out to be one in which people find the contact very meaningful, very quickly, because they haven’t had access to normal contact [before].”

“It doesn’t work if you do very stunted-up documentaries, you know, let’s follow [radical preacher] Anjem Choudary and [former EDL leader] Tommy Robinson around and they’ll play up to the cameras,” he adds. “Then you get a sort of amplification – and everyone plays up to it.”

***

Too often, info-tainment like this sacrifices reality for the most incendiary storyline or biggest characters.

Even superstar immigrant “success stories” can feel alienating for those watching. For example, a recent row was sparked by Channel 4’s documentary My Millionaire Migrant Boss, in which four unemployed people work for British Palestinian multi-millionaire Marwan Koukash. He came to Britain with £200 in his pocket, and made millions as an entrepreneur, starting up a corporate training company.

The “lazy Brits” angle is played up in the show, and audiences have both been complaining about the participants’ laziness and accusing producers of an unfair portrayal.

“There seems to be this pressure on refugees to come and hit the ground running and integrate and do stuff,” says Dima, a 29-year-old Syrian refugee who has been studying and working in London for three years, and prefers me to use her first name only. She mentions the award-winning cheese business in Yorkshire set up by Syrian refugees.

“I appreciate the positive coverage, people being portrayed as the successful individuals who made it – I understand that this is very much needed to change the perception,” she says. “However, at the same time, it could be, in smaller communities, perceived as the norm, whereas it’s not the norm.”

Certain documentaries have followed Syrians arriving and settling in remote towns, like the BBC’s Hotel for Refugees, which tells the story of a 20-year-old Syrian arriving in a small Catholic town in the west of Ireland.

Dima believes journalists telling these stories should “tread carefully” in their depictions of refugees. “I get really angry when the refugees are constantly portrayed as pure victims, because it takes away some of their dignity as well,” she says. “The media generally need to take it on a case-by-case basis. This is one of the things I constantly think about.”

From those I speak to, immigration TV works better when it aims to bring “ordinary” people together.

“I come from TV, and I understand the production values and the things that make TV watchable… The purpose of [such] TV formats is to challenge and engage people,” says Farah Jassat, a journalist and producer who is on sabbatical from the BBC and speaking in a personal capacity.

“I wouldn’t be one of those people that just says all of these social experiments don’t merit any value… it’s just about whether it conveys authenticity. So I felt that My Week as a Muslim didn’t really convey as much authenticity as it could have if it was, for example, following someone who actually was Muslim,” she says.

Like Katwala, she prefers the Big Brother format of bringing a variety of individuals together and filming their interactions. “Lots of people criticised [Muslims Like Us] but… it did a good job in at least showing a BBC One audience that Muslims have different opinions,” she argues.

“You have to remember that different TV programmes have different audiences. You wouldn’t do that on BBC Four, on BBC Four it would be facile, but for a BBC One audience, it may have educated them slightly at least not to view them as one monolithic block.”

***

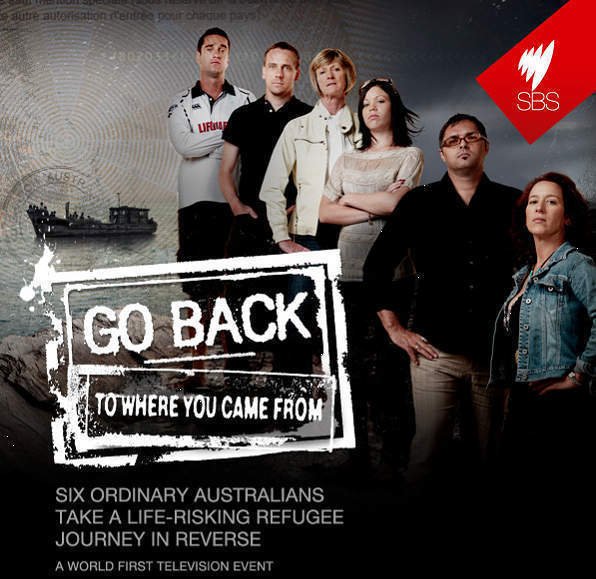

Neither TV producers nor audiences should dismiss the “social experiment” format as automatically misleading. There have been great success stories, Australia’s Go Back To Where You Came From – which shook the country’s conversation on asylum seekers when it first aired in 2011 – is an example cited by many immigration experts.

The documentary series sent six Australians to do a refugee’s journey to Australia in reverse, deprived of their wallets, phones and passports, encountering immigration raids, living in refugee camps, and travelling in leaky boats across the sea. It had the highest viewing figures on the SBS network that year, was the top subject trending on Twitter worldwide, and inspired campaigns and public debates.

“Reality TV is a powerful and emotive form drawn from the documentary tradition of observational film, direct cinema and cinéma vérité,” the Australian documentary film-maker and academic Jeni Thornley wrote at the time, analysing the format’s impact. “In such a social experiment, using the Survivor and Big Brother mode of reality television, powerful emotions erupt.”

Go Back to Where You Came From. Photo: SBS poster

Questioning whether the reality TV mode simply creates “a performance” of “enforced authenticity”, Thornley praised the show for offering “a more humane perspective” of the movement of people, but suggested it may not go beyond the “unhappy performative” – of individuals sympathising with migrants – to the state changing its policies.

And this is often where the limits of reality TV lie. It gives us characters, story arcs, and a view we might never have encountered. But it doesn’t change our opinions enough to shift attitudes. According to experts, that will only happen when new arrivals or longstanding ethnic minority communities are depicted simply as people going about their lives, rather than a case study.

“Popular culture and media portrayals make quite a lot of sense to people as a story about how things change,” says Katwala. “So, the black footballers of the Cyrille Regis era, or Nadiya on Bake Off, people actually use these things now to navigate themselves around. That kind of matters.”

However, he finds it takes “a long time, another generation, to get the presence as normal, as opposed to the presence as niche”, giving the example of Asian families arriving on Eastenders. “It takes quite a bit of that when the gay person, the Asian girl, when they’re not there to portray the issue,” he observes, noting that EU migrants like Poles are not yet being portrayed as simply part of British life.

“These sorts of reality-type things are doing something – they’re bringing a presence in,” he says. “Probably still in the kind of ‘it’s an issue we need to talk about’ mode than in normality, but I think it can still be a step in the right direction.”

McNeil urges the media to portray people with ethnic minority backgrounds as incidental rather than integral to their story. That’s when he feels attitudes begin to change.

“This concept of migrants as ‘other’ does not get necessarily overcome by telling a story,” he says. “It can do, potentially, if you tell a story about a person whose experience as a migrant is very ordinary and mundane, but that story can get told more effectively by just witnessing migrants doing ordinary stuff.”

That’s one TV experiment that feels a long way off.