No established politician in any European democracy has achieved over the past few years what Boris Johnson did in the 2019 election. Of course, there are circumstances about the Conservatives’ victory particular to Britain. Nowhere else in Europe has a first-past-the post electoral system. Nowhere else has the principal opposition party been led by a man who on security matters appears devoid of patriotism. Nowhere else has a parliament spent a year trying to thwart a referendum result after two-and-a-half years acting to honour it.

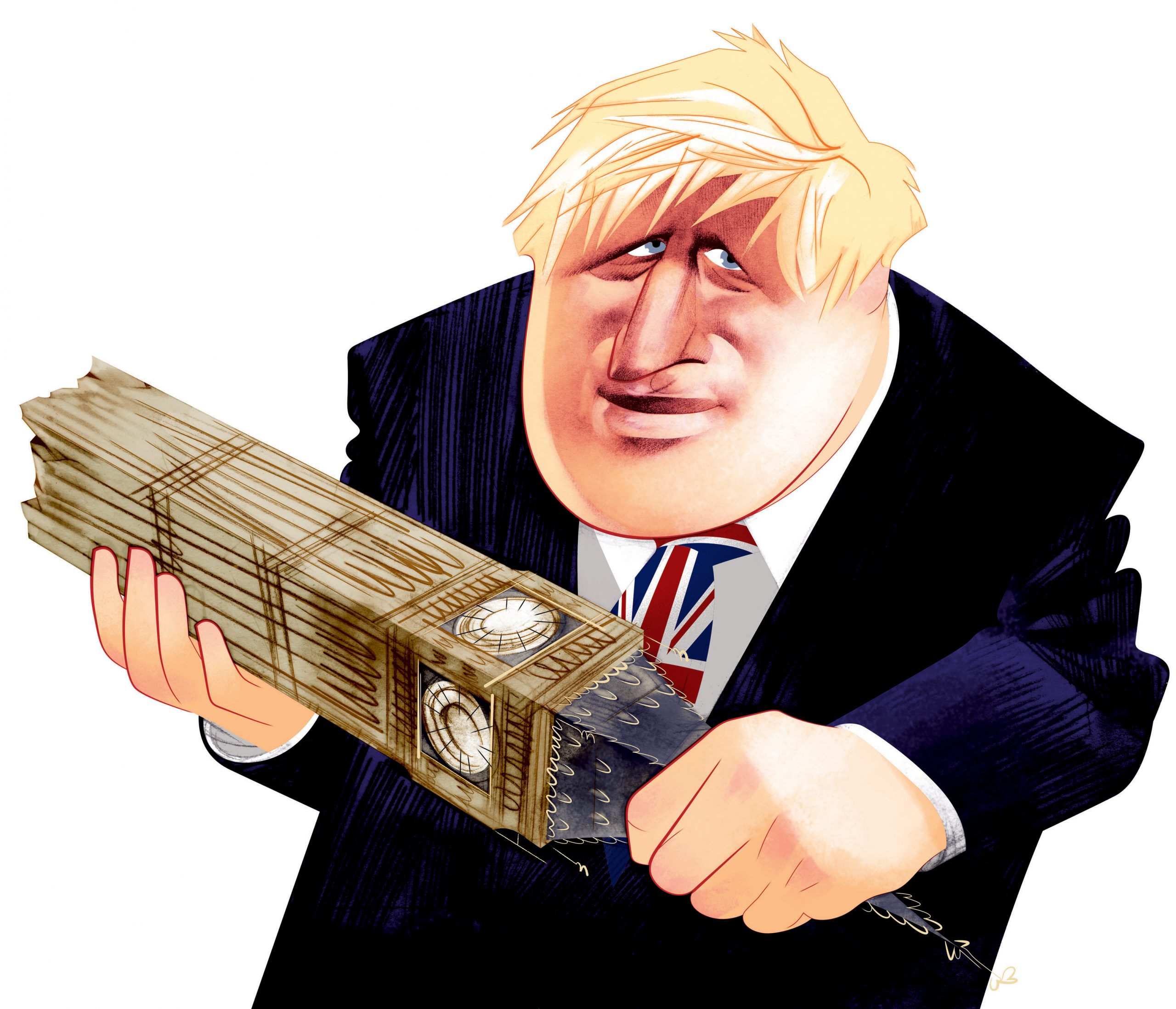

But Johnson was not just fortunate. His singular character rescued Brexit from a chain of events that same character set in motion, when Johnson spent a careless weekend after the referendum in 2016 tossing away the Conservative leadership. His willingness to enter the realm of risk, his eagerness to trade his dignity, his indifference to conventional pieties and mundane detail all arise from that character, at the centre of which is his pagan energy.

His is not a paganism drawn to classical stories of hubris and nemesis. He repudiates Ananke, the goddess of necessity whose net imposes unavoidable limits on gods as well as mortals. He is more a would-be Theseus, who, consumed with emulating Heracles’s feats, took Ariadne’s help to slay her half-brother the Minotaur only to abandon Ariadne far from home, on Naxos, perhaps simply because he could.

In a culture that is still largely ethically Christian, this overt paganism should be a political liability. Yet his pagan vitality has proved his political asset. In an age of distrust between the governed and the parliamentary and technocratic class, he stands apart from his caste. British politics has been trapped inside deceptions and hypocrisies. The voters Johnson mobilised have listened to politicians who declaimed they accepted the referendum result while doing everything they could to stop Brexit happening. They heard a Speaker bellowing about the rights of parliament in the obvious hope of obstructing the decision of the electorate. They watched Jeremy Corbyn and his acolytes pretend the Labour leader was a peacemaker when they discern a man who has supported pretty much every anti-British, anti-Western, anti-Israeli cause on offer for decades. Those who asked them to ignore these untruths are the same people who demanded they see Johnson as an unforgivable liar.

The straightforwardly Leave part of Johnson’s Conservative coalition also knows that part of the political class judges them as severely as him. These voters have been damned for purportedly believing Johnson’s lies on the side of a bus, and are thus implicated in his original sin. Johnson’s gift to them through the autumn parliamentary crisis and winter election is that he talked and acted as if, in casting a vote when asked their opinion, they did nothing for which they should be ashamed. Theresa May made it her duty to act on their victory. But sincere as she was, she appeared as time went on to begrudge the necessity of doing so. She treated Brexit as a moral burden. Johnson rewrapped it for Leave voters as an action-man gift for Christmas. May thought that if she told parliament often enough what it must do to preserve the electorate’s trust over the referendum, MPs would eventually understand what was required of them. By contrast, Johnson used his insolence to bulldoze through the hypocrisy into which parliament had sunk.

Paradoxically, though, Johnson was helped by the Christian ethics his paganism repudiates. Aversion to the hypocrisy evident in the gulf between the promise to let voters decide and the refusal, from an inward conviction of superiority, to accept their answer has deep Christian roots. Christ, in his great denunciation of Pharisee hypocrisy in Matthew 23, cast judgement on those who “say, and do not” and “strain at a gnat, and swallow a camel”, blind to the gulf between an outward demonstration of righteousness and an inner absence of mercy. Since caring about the possible moral distinctions between available actions requires a care and rectitude Johnson seems to see as pointless and life-negating, he is not unhindered, but dependent on, that which is largely alien to him.

His grander fortune is the partial affinity between paganism and the part of English Christian heritage that stands against radical Protestantism – whether in its religious or secular form. This tradition insists there is a virtuous elect, and a sharp separation between the sacred or teleological and the earthly or enduring contingencies of place and human weakness. In 1647, the Puritan government passed a law outlawing celebrating Christmas, believing the festivities to be a pagan custom. When the mayor of Canterbury tried to enforce the diktat that shops stay open and no mince pies be eaten, the cathedral city’s citizens rioted. In the New Year, they took up arms for their once hated king against parliament. It did Charles I no good. But with the Restoration, the attachment to Christmas defeated parliament.

The precariousness of Johnson’s search for political intensity will one day crash into those pagan gods of limits to whom he offers no sacrifices. Theseus becomes King of Athens. Then he roams. Driven to sail with the Argonauts in quest of the Golden Fleece and embark upon a forbidden descent into the underworld to abduct Persephone, Theseus loses his kingdom. He meets his death off a cliff, murdered by the ruler of the island where he is exiled. But to the classical pagan imagination no god, not even Ananke, rules alone. When the sixth-century Athenians wanted a mythical champion for their new democracy, they opted for the stories of Theseus, complete with their heroic deeds and terrible violations.

This article appears in the 18 Dec 2019 issue of the New Statesman, Days of reckoning