Ireland has an awful lot riding on Brexit. If it wasn’t already obvious that the stakes at play for Dublin are so high as to be existential, then the welcome its parliamentarians today gave to Michel Barnier – the European Commission’s chief negotiator – makes things unnervingly clear.

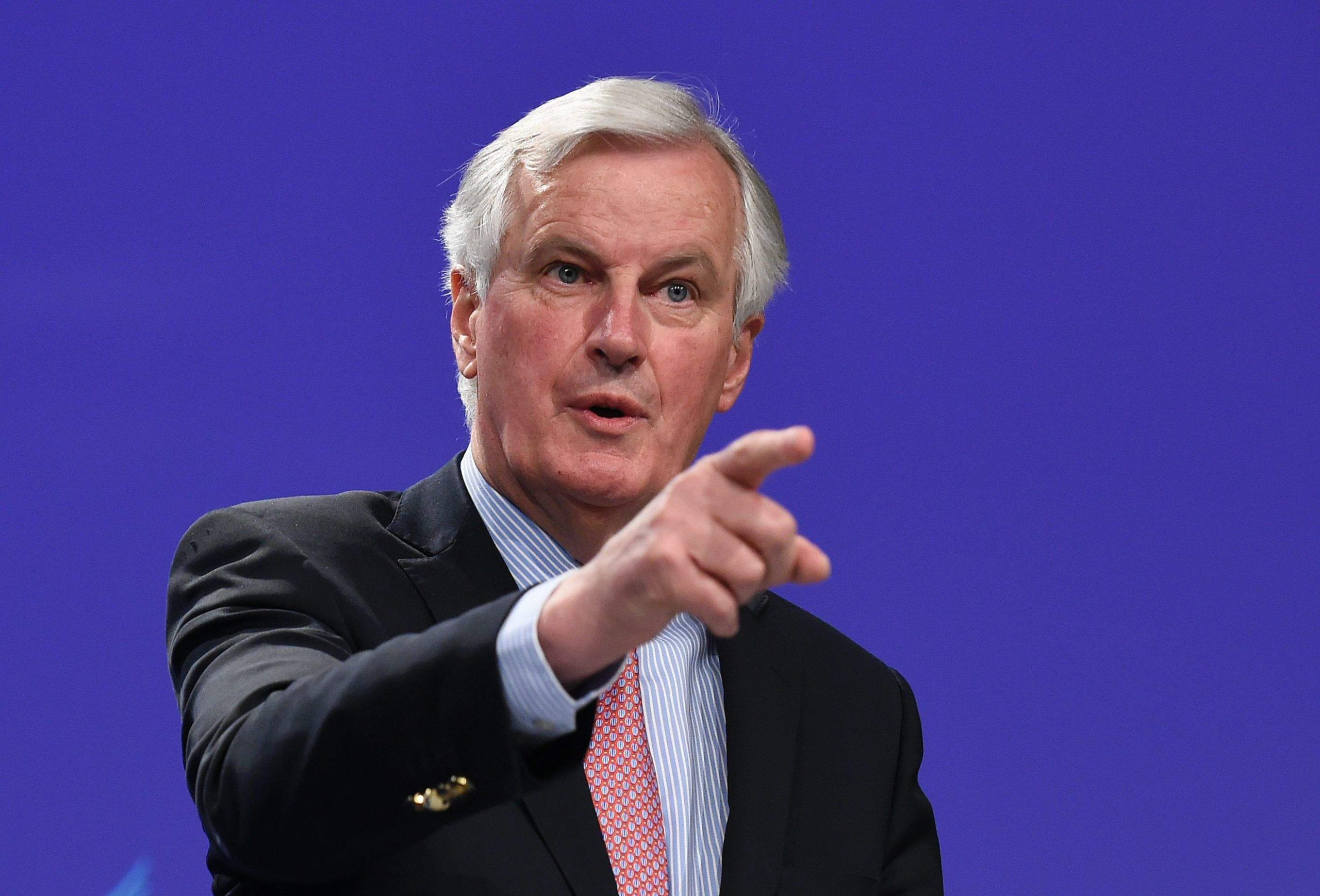

Barnier, who is held in high regard both in Dublin and by the nationalist cohort at Stormont and Westminster, kicked off his visit with a joint address to both houses of the Oireachtas. That honour puts the Eurocrat, as one government senator told the FT, “on the same pedestal as John F Kennedy, Nelson Mandela and Francois Mitterand”.

Judging by the speech Barnier delivered, it’s fair to say that Enda Kenny didn’t book him for oratorical flair. The speech was, for the most part, unspectacular. But Dublin’s courtship of Barnier is transactional, as has been its approach to the Brexit negotiations thus far. By aligning itself keenly and tightly with the EU27 rather than the UK, its hope is to enable a settlement whereby its new economic relationship with Brexit Britain is as close to the status quo as possible – averting the need for the imposition of a hard border with the North.

Does Barnier’s address tell us anything new about how realistic that objective is? Yes and no. For all its symbolic significance, the speech in of itself was unspectacular. Little new of substance was said. Some commentators have seized upon Barnier’s unremarkable admission that “customs controls are part of EU management” as evidence that an unwieldy hard border is inevitable. In truth, he was restating something that’s been obvious to Irish politicians of all hues since 24 June 2016 – that the current light-touch customs regime that regulates the passage of some goods between the Republic and North will have to be ramped up in some way once the UK leaves.

That alone isn’t really news, convenient though it might be for some. Much more significant was Barnier’s reassurance that resolving the Irish question remains one of the EU’s foremost priorities as negotiations begin. At this stage, earning and maintaining goodwill in Brussels is incredibly important – a truism that Theresa May seems incapable of understanding – and Barnier’s warm words will lend weight to an assumption being made in most quarters: that however hard a line the EU takes with Britain, it’ll happily fudge a settlement that minimises pain on the island of Ireland.

Not that everyone welcomed his intervention. “It’s the EU deliberately trying to interfere tangentially in the NI general election!” the Democratic Unionist Party MP Ian Paisley told me. “It’s quite pathetic.” Whether or not you agree with that analysis of Barnier’s motives, Paisley is right on one thing: any statement on the border, however anodyne, will have electoral ramifications in Ulster next month.

No amount of banal reassurance can disguise the fact that uncertainties remain. There will be some hardening of what is currently an almost entirely imperceptible border. It’s safe to file Barnier and the commission’s “flexible and imaginative” solution in the same drawer as the “seamless and frictionless” border proposed in HM Government’s Brexit white paper. As things stand, these insistences amount to little more than wishful thinking. While the will is there, few are confident that anyone – not least the UK government – have any idea how to pull it off. That Barnier also nodded to the testy relationship between Jean-Claude Juncker and Theresa May is also ominous. Ireland’s assiduous charm offensive will amount to nothing if the UK walks out of negotiations and crashes out of the EU without a deal. The current consensus is much more precarious than anyone would care to admit.

All of this adds succour to the nationalist case that Brexit will inevitably be a retrograde step – and that some harmful hardening of the border is inevitable. Sinn Fein has put Brexit and the border front and centre of its Westminster campaign – “No Tory Cuts, No Brexit, No Border” – and is mounting an audacious challenge to the DUP’s Westminster leader Nigel Dodds in North Belfast. The moderate nationalist Social Democratic and Labour Party will also fight hard on an anti-borderist platform. By some distance the most thoughtful contributors to the debate on the North’s post-Brexit future, it has forced David Davis to admit that Northern Ireland would automatically join the EU should it back reunification in a border poll. Though Sinn Fein President Gerry Adams’s call for a referendum on reunification was no surprise, should the border reality bite as hard as some fear, that prospect could provide a shortcut back to normality.

The Brexit backlash played a big part in denting the DUP in March’s Assembly elections, where it lost 10 seats and came uncomfortably close to parity with Sinn Fein. Could Barnier’s confirmation that new border measures are inevitable have put them on collision course with another electoral reckoning?