The historic outcome of the EU referendum coincided with a 10 point surge (between May and June) in people saying immigration is the biggest issue facing the country in Ipsos MORI’s Issues Index. And in the final two weeks before the polls opened, our Political Monitor showed that immigration ranked as the single biggest issue which would affect how the public voted in the referendum, overtaking the economy.

The Issues Index has seen concern about immigration steadily increase over recent years, and so it was already a central theme in the debate long before Nigel Farage revealed the now infamous Breaking Point poster. Here are four reasons immigration was the key to the result which unfolded on 23rd June:

1. Voters didn’t have to be affected by immigration personally

We know people said immigration was the single biggest motivating factor for how they would vote, ahead of the economy, sovereignty and impact on public services. However, despite one in three saying that immigration was the top issue for them, in a different study over half of people said that it had had no impact on them personally.

For those saying that they would vote Leave, half said that they had experienced no impact personally from EU immigration. When breaking this down by age, older people were less likely to be affected by immigration than young people, with 59 per cent of over 55s saying that had EU immigration had no impact on them personally. So for so-called Project Fear, it was difficult to find messages which would resonate with people in the same way as they could for the economy – because for Leave voters it was about something more intangible and fundamental than how it affected them personally.

2. Total immigration control mattered most

The ‘red line’ for many voters was total control over immigration, which many saw as more important than access to the EU single market. Over half of the general public said that the Government should have total control over immigration, even if it meant leaving the EU, compared to the 33 per cent who felt the benefits of remaining the EU outweighed the Government’s control over immigration.

Furthermore, opinion was divided on free movement. Forty-two percent thought that Britain should continue to allow EU citizens to come and work in the Britain in return for access to single market and an almost equal number said that Britain should stop EU citizens coming to live and work here with new immigration rules – even if that restricted Britain’s access to the single market. A further poll for BBC Newsnight after the vote showed that this measure had not shifted with a opinion split slightly in favour of limiting movement. This will be something to look out for as negotiations the UK’s future relationship with the EU get underway.

3. Leave voters were more set in their minds

Ipsos MORI’s longitudinal study on attitudes to immigration revealed that there is huge amount of churn in the people who are more positive about immigration and want to see it increase. Contrary to expectations of this group of people being a stable core of liberals, their views are more likely to change than those who want immigration to decrease. Only four in ten of those who said they would like to see the number of immigrants coming to Britain increased in February of this year held the same position in June. Over a third changed their minds to say that they wanted the numbers reduced.

This was also true for the referendum debate. When prompted with potential changes to immigration levels, remain supporters were more likely to waver in their support than leave voters. Those remain voters who said they would still want to stay in the EU if immigration was at the current level of 260,000 per year was high, at 82 per cent, but that dropped to 46 per cent if immigration increased by an additional 100,000 per year.

4. It was the older generation what won it

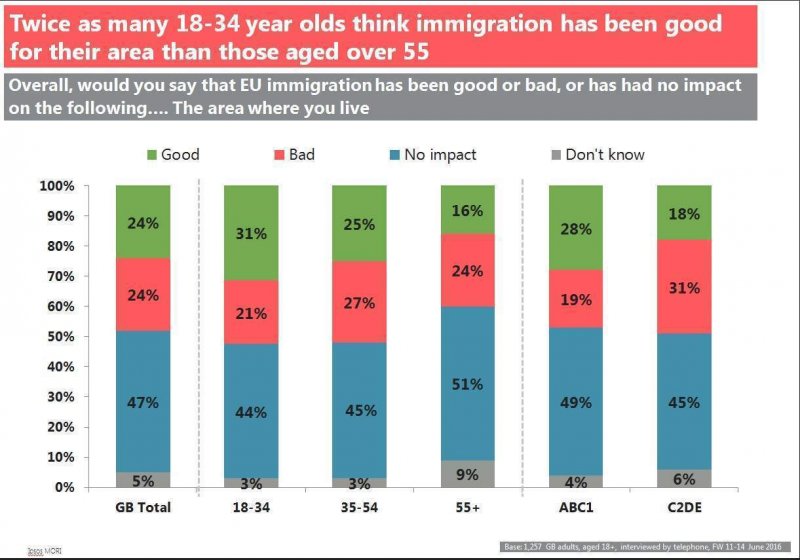

In the week before the referendum, Ipsos MORI’s Bobby Duffy predicted that if young people didn’t turn out to vote in sufficient numbers, the result would be Brexit. Remain had a huge advantage with the young. Our final EU referendum poll showed that two in three 18 to 34 year olds said they would vote Remain compared with 40 per cent of those aged over 55. The generational gap grows further when looking at attitudes towards immigration. Britons aged between 18 and 34 are twice as likely to think that immigration has been good for their area than those aged over 55. As we know from the general election turnout, they are less likely to turn up and vote. Unfortunately for the Remain camp, it seems that they didn’t show up in sufficient numbers on the day.

Aalia Khan works for the Social Research Institute at Ipsos MORI.