Let’s get real. The resignation of a single politician, however long-serving and charismatic, does not turn an unhappy Union into a happy one. Nicola Sturgeon has served for so long as her country’s leader because so many Scots do not feel comfortable inside the UK. She is going because it had become clear there is no short-term route to independence. But the question to which she had seemed some kind of answer has not gone away.

We are living through a slow crisis of Britishness. (Can there be a “slow” crisis? Hmm. Well in this case, friends, there is.) We have been used to seeing “nationalism” as a Scottish exception but, really, it is a symptom of a British – or rather London – disease.

Keir Starmer seems to get it. When he talks about Westminster “hoarding power” and warns Scottish Labour about complacency, he is in the right area. Unionism is not a default position any more – if it ever was. Through the second half of the last century, and well into this one, “government” often felt like something being done to Scotland, rather than something Scotland owned.

[See also: Will Nicola Sturgeon’s resignation impact the SNP’s electoral fortunes?]

It’s not a new complaint, nor one limited to Scotland. Around the 1707 Union, the Scottish political thinker Andrew Fletcher of Saltoun, bitterly compared London to the swollen head of a rickety child: “That London should draw the riches and government of the three kingdoms to the south-east corner of this island, is in some degree as unnatural as for one city to possess the riches and government of the world.”

After the Second World War and the reconstruction of the Clement Attlee years, not much knitted Scotland and England together as London became steadily more powerful. It has become fashionable to deride the devolution plans enacted by New Labour in the 1990s, but creating a Scottish parliament was a necessary response to growing uneasiness in one of the world’s more centralised states.

If the Sturgeon resignation offers unionism a brief fresh start, then the response must be serious. At least one of the major departments of state should be moved to Glasgow or Edinburgh (which is currently losing its financial industry, on which much of its prosperity depended).

[See also: Could Kate Forbes make a comeback?]

The Ukraine war requires a major rethink about defence: rebuilding the army and navy should begin in Scotland. Given its geographical advantages, Scotland should also be a centre for the green energy revolution. Clearing up the mess across the North Sea after the oil industry is a huge industrial project which, again, should be dealt with by Scots.

Short of big moves, Scottish nationalism will revive under a new leader and in different circumstances. Until we get away from the greedy stockpiling of power in London, tensions across Britain will never be resolved. This isn’t simply a Scottish thing. It is felt as much in Manchester, across Yorkshire, in the south-west, Wales and Northern Ireland.

The Boris Johnson-Michael Gove levelling-up agenda was, in theory, a virtuous response, but the Conservatives cannot offer the more general revolution in British governance that is needed. “Red Wall” or not, conservatism is deeply rooted in the south-east and Home Counties. Its centre of gravity is there.

Does Labour really have the radical energy to change much of this, even with a boost in Scottish seats? Gordon Brown provided a blueprint and Starmer is talking the talk. But… we shall see.

[See also: Three cheers for Nicola Sturgeon for knowing when to walk away]

In the short term, Sturgeon’s resignation arrived like a wet fish whacked across the rosy cheeks of Scottish nationalism. It formalised what had been informally clear: nothing is going to happen on independence any time soon.

Since the Supreme Court judgment on 23 November last year, the SNP has had no coherent strategy for achieving another referendum. The Sturgeon idea, simply to assert that the next election would be a de facto referendum, was constitutionally nuts – parties don’t get to tell the voters why they are voting – and politically perilous for the SNP. It would also have led Scotland towards a wilderness of civil disobedience.

It was starting to look as if, in taking this wild wheeze to a special conference in March, she might have lost, and been forced to resign in humiliation. If you want the simplest explanation for why she went now, that’s it.

Already the contest to replace Sturgeon reveals that the SNP understands its cause has become, yet again, the long march. Older contenders such as John Swinney, 58, and Angus Robertson, 53, have ruled themselves out. This is a younger politicians’ game.

This week I talked to Humza Yousaf, at 37 an experienced minister and currently the Scottish health secretary. He had already expressed doubts about Sturgeon’s general election scheme but when I asked him for his alternative, he emphasised the need to develop policy and support, rather than focus on “process”. And he’s absolutely right – to the extent that the SNP’s fundamental problem is that Middle Scotland cannot yet see an economic or industrial strategy after independence that doesn’t make it poorer.

Every sentient Scottish voter understands that the SNP’s long role in governance has not been exactly triumphant. Whether it is the scandal over the unbuilt island ferries, or the failure to improve Scotland’s atrocious record on drug deaths, or to give working-class Scottish children a better education, or to upgrade dangerous roads, there’s a miserable side to its record. Bizarrely, given the importance of Scottish culture to Scottish nationalism, the Scottish government is – like the London one – slashing arts funding across the country.

[See also: A Scottish transgender rapist has exposed Nicola Sturgeon’s dangerous complacency]

For long enough, Sturgeon and the SNP were able to rise above this through a combination of rhetoric and symbolism. The rhetoric was directed at a succession of failing Tory administrations in London – fish, barrel, shotgun – and championing the left-liberalism of Scandinavia. The best example of the symbolism was the “baby box” scheme, based on a Finnish model, which gave every new parent in Scotland a package containing everything from mittens, socks and fleeces to thermometers and baby books and, slightly oddly you might think, a condom.

Although rhetorically to the left of any London administration, Holyrood under the SNP was reluctant to use its powers to raise taxes much (though they are slightly higher now than in England).

According to the Institute for Fiscal Studies, recent reforms mean that the poorest tenth of Scottish households will be £580 per year better off than they would in England or Wales, because of higher benefits. Meanwhile, the richest tenth will lose around £2,590 because of higher income tax. Inside this limited fiscal envelope, the SNP has been more generous on welfare – including the £25 weekly Scottish Child Payment to help lower-income families. It introduced free university education, scrapped prescription charges, built more than 100,000 affordable homes and banned fracking.

The problem was always that this leftwards tilt was based upon no discernible industrial or economic strategy, and an economy too small to give the Scots the welfare they believed they deserved. Proposing a customs border with the rest of the UK, Scotland’s biggest market – which is what EU membership would have meant – was hardly an answer. Much of the more lavish social spending came from a funding formula from London which was itself relatively generous.

[See also: Three cheers for Nicola Sturgeon for knowing when to walk away]

These basic facts are well understood in Scotland, which is why the SNP has been unable to muster a secure majority for independence. You might have thought that the Brexit campaign, Nigel Farage, Boris Johnson, the Liz Truss interlude, and the behaviour of London politicians during the pandemic was a kind of giant (un)controlled experiment to provoke Scottish voters into leaving. Was there ever a perfect time to make the case for Scottish independence? Yes, and we have been living in it for the past few years.

Yet Scottish voters were deeply reluctant to jump, even with the dedicated and loquacious leadership of Sturgeon. Dedicated or not, she hasn’t left the party in a happy place. There is a danger for the SNP that the leadership contest now degenerates into a vicious fight about trans rights. The two other contenders so far – Ash Regan, who resigned as community safety minister over the gender self-identification bill, and Kate Forbes, the finance secretary, who is a devout Free Church Presbyterian and is against gay marriage, abortion and the trans legislation – are ranged against Yousaf, who passionately supports gender-recognition reform.

Culture wars may therefore engulf the contest, in a way that has not yet happened at Westminster. Battles over trans issues have already ripped apart liberal media institutions, from the Guardian in London to the New York Times. The British Labour Party is struggling hard to avoid being sucked into one of the most poisonous of modern arguments.

Nicola Sturgeon departs to general applause for her extraordinary political skills. But history may conclude that her failure to produce a strong economic case for independence was a devastating one. By concentrating so much on the liberal tone, and sounding right, she omitted the basic political work on which a solid independence majority could depend.

I remain convinced that it would be a huge mistake for unionists to shrug and declare victory. We still live in a grossly overcentralised and economically inefficient state. From Cardiff to Belfast to Manchester, never mind Scotland, they know it. And, in fact, in Scotland, very quietly, the situation is becoming more comfortable than in other parts of the UK.

Why? Ask yourself: in the modern world, what is the point of nationalism? It’s not about claiming to be better than anyone else. It’s about holding on to local cultural distinctions, having your own conversation in your own language about your own priorities. In those ways Scotland already has most of what Scotland wants. The problem isn’t Scottishness. It’s Britishness. Who do the rest of us really want to be?

[See also: Rishi Sunak, the man who isn’t there]

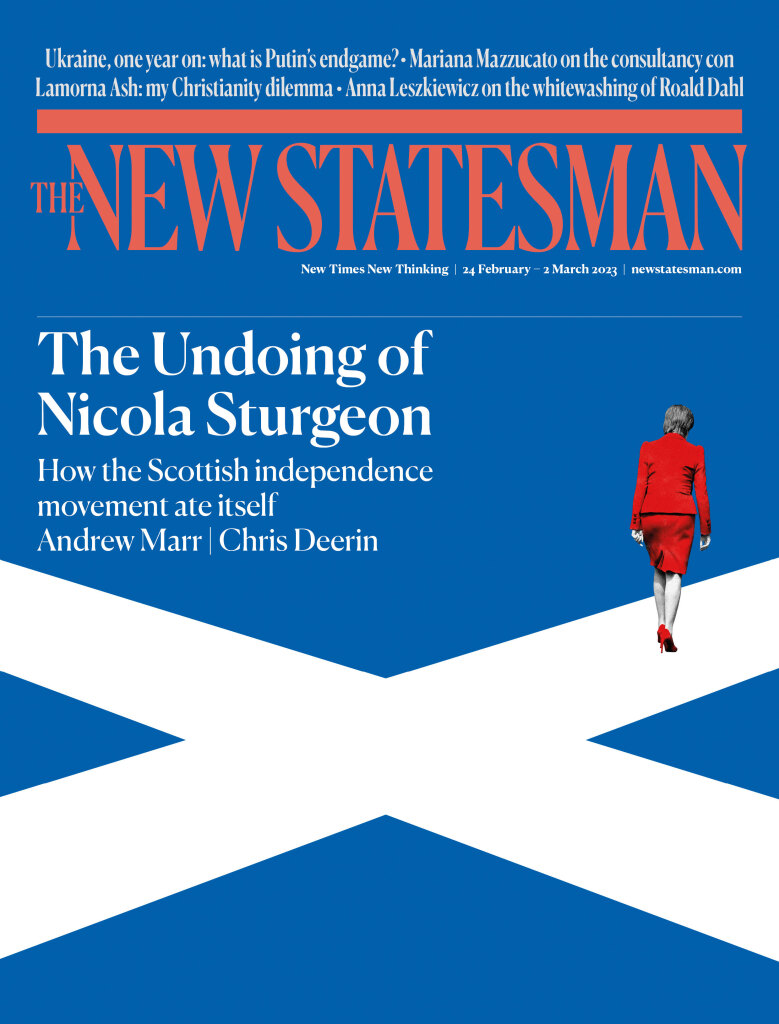

This article appears in the 22 Feb 2023 issue of the New Statesman, The Undoing of Nicola Sturgeon