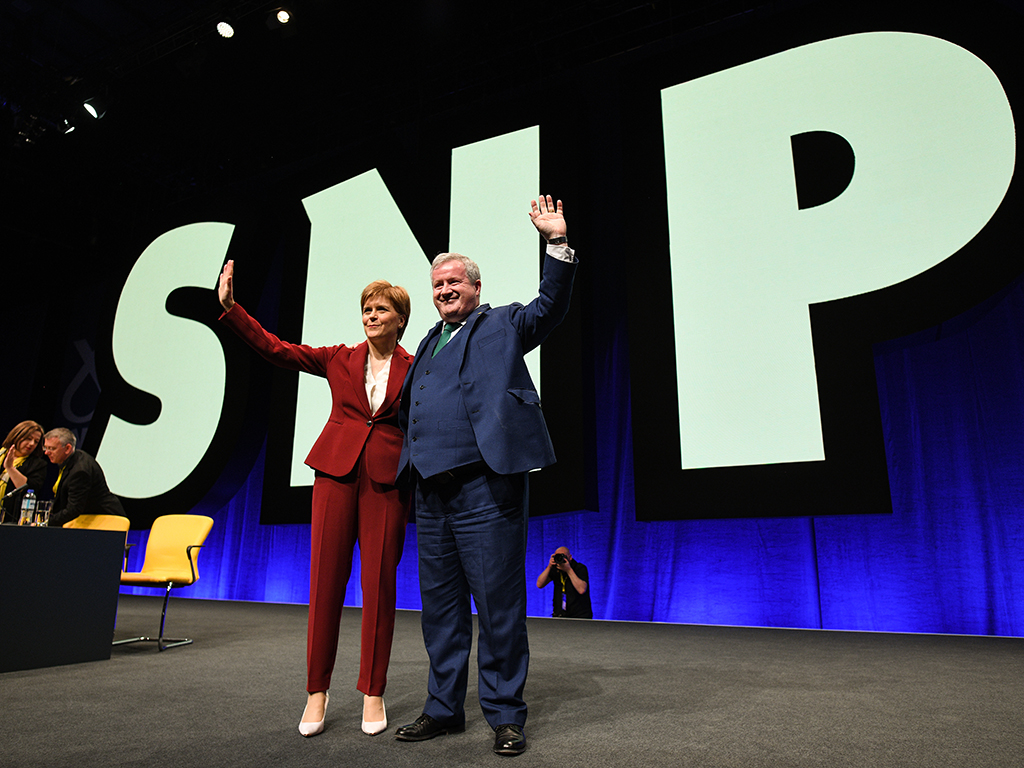

The resignation of Ian Blackford is confirmation that Nicola Sturgeon’s grip on her party is slipping. Maybe only a little, maybe a bit more than that, but it is slipping.

A dose of the Joanna Cherrys appears to be taking hold of the SNP both at Holyrood and Westminster. Cherry, the party’s most formidably independent-minded MP and a regular critic of the First Minister, suddenly finds herself just one of a crowd. For so long the phrase “SNP rebel” has been almost an oxymoron, given the slavishly devotional nature of nationalist politics under Sturgeon. Within her party, she has had the easiest of rides since becoming leader in 2014, but a series of convulsions is breaking out that indicates that something is changing at last.

Blackford had been the SNP’s leader at Westminster for five years, and last month narrowly avoided a challenge for his post from Stephen Flynn, regarded as among the most promising of the party’s younger MPs. Now it appears that pressure from the parliamentary party has forced his hand, and he has quit just before the group’s AGM on 6 December. Blackford, whose turgid performances at Prime Minister’s Questions have made him something of a figure of fun in the Commons, has been supported by Sturgeon as a safe pair of hands and someone who is unlikely to test her authority. Friends say he has recently been flagging, however, and for some time now members of the Westminster group – not just the temperamentally disloyal – have felt neglected and ignored by the First Minister. Flynn, if he is Blackford’s replacement, is likely to want a more influential role.

There is also an ongoing SNP uprising over the Scottish government’s gender identity reforms, which surfaced again on Wednesday (30 November). In any normal party, six MSPs going against the party whip would be a bit ho hum, a not uncommon occurrence among smart, principled people who are able to think for themselves. And while the numbers are certainly not enough to prevent this controversial and ill-considered legislation from going through, it is an insurrection on an unprecedented scale amid the ultra-faithful nationalist bloc at Holyrood.

Ash Regan, who resigned as a minister rather than support Sturgeon’s proposal for self-identification of gender, again refused to vote with her leadership, this time in relation to an intervention in the debate by Reem Alsalem, the UN’s special rapporteur on violence against women and girls. Alsalem has voiced doubts about the Scottish government’s reforms, fearing they could be abused by predatory men to access women’s spaces, and has called for them to be paused. The Scottish Conservatives wanted these concerns to be officially noted by parliament, while the nationalist leadership very much didn’t. Regan, along with her fellow SNP MSPs Ruth Maguire, Michelle Thomson, Stephanie Callaghan, Annabelle Ewing and John Mason, abstained rather than back Sturgeon’s position. It might not seem like much, but even mutiny on this moderate scale will enrage the First Minister, who has shown no interest in compromising with or even listening to her critics on the issue.

This also followed an event on Tuesday, where Sturgeon’s speech about violence against women and girls was interrupted by a woman who shouted “shame on you”. Before she was removed, the woman told Sturgeon: “You are allowing paedophiles, sex offenders and rapists to self-ID in Scotland and put women at risk. Women campaigning for women’s rights is not against trans people… You’re letting down vulnerable women in Scotland, not allowed to have their own spaces away from any male.” The First Minister is not used to being confronted in this way.

[See also: The SNP can do better than Ian Blackford]

That’s not all, though. Sturgeon’s plans for a National Care Service are also coming in for a pounding. This time, the critics are the members of Holyrood’s Finance and Public Administration Committee, three of whose seven members are SNP MSPs. A fourth is a Green MSP, whose party is in coalition with the Nats.

There is widespread concern among care professionals and councils as well as politicians and auditors at the way the care service legislation is being bundled through parliament before proper cost estimates have been made and decisions about its final shape have been taken. Sturgeon wants to push the bill through and then fine-tune the care service later through secondary legislation, which is less scrutinised and rarely debated. Kenneth Gibson, the SNP MSP who chairs the finance committee, said that “major bills should not be implemented via secondary legislation… The significant gaps highlighted throughout our report have frustrated the parliamentary scrutiny process.” There is particular worry that the government has grossly underestimated the cost of the new service, which Sturgeon sees as a key part of her legacy.

There was also the general unease that greeted Sturgeon’s pledge last week to forge ahead with her strange wheeze to treat the next general election as a de facto referendum on independence. After decades of patient politicking by the SNP, some of her more thoughtful colleagues see this strategy as a mad dash for the barricades that is more likely to fail than succeed, substantially setting back the independence cause. Rather than allow her successor to continue the long game, Sturgeon’s ego seems to demand a last charge at the big dream.

What should we make of all this? Certainly, it seems like Sturgeon’s imperial approach to running the SNP is starting to chafe. Her circle of advisers has always been tiny – it includes her husband, Peter Murrell, the party’s chief executive. It is probably inevitable that as time has passed her largely unconsulted colleagues have grown weary of simply doing what they’re told – there is a substantial amount of lobby fodder on the SNP backbenches, but there are some sparkier types too. And as Sturgeon’s era draws closer to its end, it’s also inevitable that her authority will start to wane as her colleagues look to the future. There are those who want her gone, and those who want her to feel some pain before she goes – that’s what comes of ruling by fiat. She’ll also be aware that in politics rebellion can be infectious.

Perhaps the biggest danger facing the First Minister now is the risk that all this upheaval could poison her legacy. It is a loss of control that no one saw coming, as Sturgeon approaches the conclusion of her long reign.

[See also: Scotland can never be an equal partner with England, in the Union or outside it]