In the end, of course, it’s about whether you do or don’t have that burning desire to make a difference. Effective, radical education reform is horrible: bruising, attritional and at times zero-sum. Those politicians who deliver – think Andrew Adonis and Tony Blair, Michael Gove and David Cameron – do so in a climate of hostility, character assassination, and constant subversion by the education establishment, among the most conservative special interest groups in the country. That’s why the difference between success and failure often comes down to an individual’s possession of fierce moral mission, of an indefatigable commitment to drive through innovations that will in time benefit children and parents, if not union leaders.

It’s been a tough journey in England, where academies, free schools, the London Challenge, Teach First and other once-controversial programmes have helped reduce the attainment gap in some of the country’s toughest areas. But Scotland has barely taken baby steps. A succession of first ministers and education secretaries has proved too timid to challenge the McBlob, the Jabba-like agglomeration of teaching unions, native “experts” and training institutions that has for decades blocked meaningful change. Down south, even moderate reformers who are reluctant to use the “Blob” phrase about the English education establishment happily apply it to Scotland.

The latest success of McBlob has been to see off the arrival in Scotland of Teach First. A charity that fast-tracks the brightest graduates into challenging schools, there is nothing particularly unusual about Teach First: versions of it operate in around 40 countries. It has its critics and its flaws, but the most recent independent studies show its teachers have had a measurably positive impact on pupils’ GCSE results. Its Futures programme, which matches sixth formers with no family history of higher education with mentors who provide advice and practical opportunities, has seen 80 per cent of those who take part attend university, compared to 17 per cent of students from low-income backgrounds nationally. Sixty per cent of those interviewed by Oxbridge received an offer, something managed by only 25 per cent of total applicants.

A quarter of its most recent teacher cohort had themselves been eligible for free school meals and/or the Education Maintenance Allowance, while 38 per cent were the first in their family to go to university, and 14 per cent were from black and minority ethnic groups, double the percentage of the current teaching workforce. Almost 400 graduates from Scottish universities have signed up to work in English schools through the scheme since 2012.

The organisation had wanted to expand its activities northwards, an ambition endorsed by both the Scottish National Party First Minister Nicola Sturgeon and the Conservative leader of the opposition Ruth Davidson. Scotland has hundreds of teaching vacancies in its schools and gaps in key subjects. In most countries, an idea that was supported across the ideological barricades by the two most powerful people in politics would stand a reasonable chance of success. That’s not how things work here. As Sturgeon launched a government tender to find a provider of a fast-track route into teaching, a campaign began against Teach First. It was tarred as some kind of failed right-wing conspiracy, rather than a programme to bring the brightest graduates into teaching. Its successes were dismissed, its weaknesses blown out of all proportion.

An even more effective McBlob tactic was to make it impossible for Teach First to meet a central requirement of the tender, which stipulated that the successful bidder must have a university partner. In a classic stitch-up, Scotland’s universities announced en masse that they would not work with Teach First. One vice-chancellor who broke with the herd and offered to collaborate found that his own education department simply refused to co-operate. Teach First withdrew from the bidding process, citing difficulty with the timescale.

This is Scottish education – a highly politicised cartel that is closed to innovation, to outside entrants, to pressure from politicians or parents. The Educational Institute of Scotland, the nation’s main teaching union, is run by Larry Flanagan, a former Trotskyist and Militant Labour councillor, who claimed the introduction of Teach First would be a “betrayal of the high professional standards we operate in Scotland”. His solution to the teacher shortage is the same lazy cliche beloved of union barons everywhere: “Fast tracking a substantial pay increase would be the best recruitment tool available to Scotland’s politicians.”

Scotland’s children badly need a hero. In Holyrood’s first couple of decades the needle has barely nudged on educational performance, particularly among the most underprivileged kids. In some cases it has gone in the wrong direction. When the nation was shown to be slipping down international charts, the SNP government simply withdrew from them. It has focused its attention on the confusing and confused Curriculum for Excellence programme, which is presented as equipping pupils for the modern world, but which lacks any kind of real cutting edge.

As Davidson wrote in the Scotsman this week, “no-one has the faintest idea whether the curriculum has actually boosted standards. All we do know, 13 years on, is that Scotland has slipped down the international Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s league table for attainment and that those nationwide Scottish surveys which the SNP has not yet abolished show a fall in literacy and numeracy standards among children in both primary and early secondary school.”

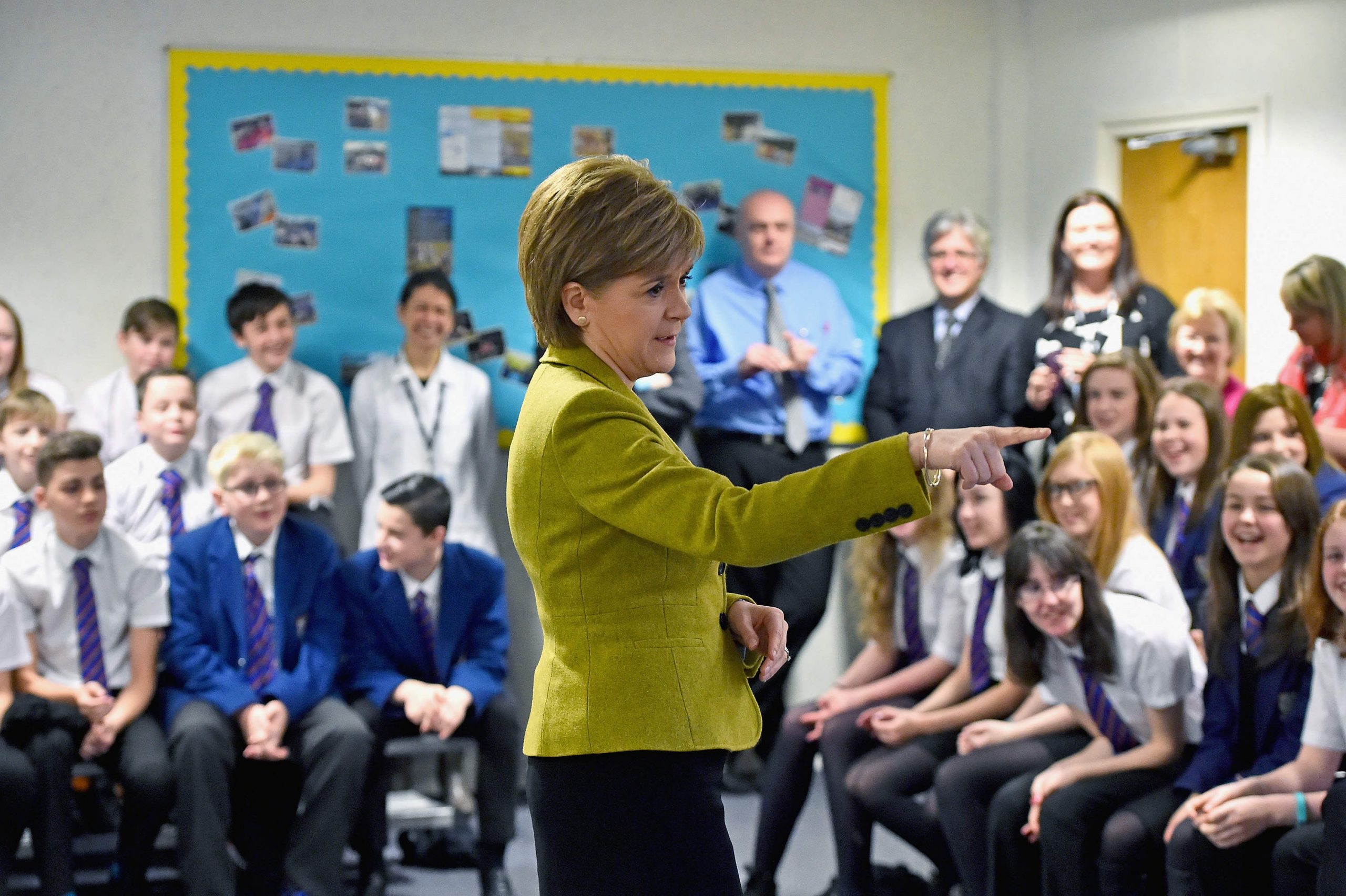

Sturgeon has promised that education – rather than independence – is her top priority. When I interviewed her a few months after she moved into Bute House she insisted “education and the attainment gap… that’s [what] I’m going to measure myself against.” She insisted boldly that “if anybody decides to be a block to making sure we’ve got the best education system then they should be moved out of the way. I’ll be confrontational with anybody if it’s about improving the educational experience of kids that come from the kinds of communities that I grew up in.”

As time passes and the evidence accrues, it becomes harder to see these as anything more than empty words. Sturgeon, it seems, is just the latest politician lacking the guts to take on the McBlob.