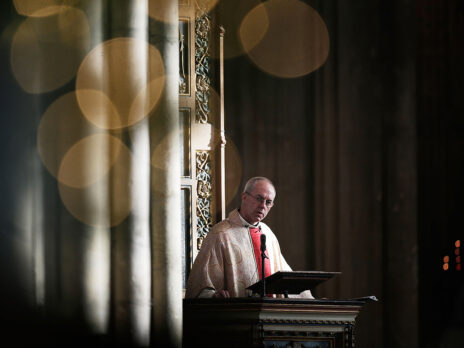

Editor’s note: This piece was originally published on 4 September 2024. It was republished on 12 November 2024, following the resignation of Justin Welby, the Archbishop of Canterbury, over his handling of a clerical abuse scandal.

There is an ancient tradition in the Anglican Church of nolo episcopari, which roughly translates from the Latin as: “I do not want to be a bishop.” It is an unwritten, and largely unspoken, rule of appointment to high office in the Church of England: if you want to be archbishop of Canterbury, you cannot be seen to want it. Those who least wish to serve, the logic goes, are best suited to the task.

And so, when Justin Welby was appointed Archbishop of Canterbury in 2012, he called his appointment “astonishing”: “I don’t think anyone could be more surprised than me at the outcome of this process.” Welby’s humility may have been genuine, but the decision could not truly have been a surprise: bookmakers had suspended betting after the odds tipped too strongly in Welby’s favour. “Since he was appointed,” the BBC’s Emily Buchanan observed, “Justin Welby has made a point of being self-deprecating, showing great surprise that he was chosen at all.”

“You get the impression that people are jockeying for power, that they’re positioning themselves without actually positioning themselves,” said Helen King, a professor of classical studies at the Open University and a member of the Church’s governing body, the General Synod. “I think people do put their hands up, in a non-explicit way.”

The principle of nolo episcopari will once more be quietly and politely on display as Welby approaches the Church’s retirement age of 70 in January 2026 (he could request an extension from the Crown until his 71st birthday if “special circumstances” demanded it, but no previous archbishop of Canterbury has done so). Despite much speculation that Welby would announce his resignation after King Charles III’s coronation last September, the Archbishop appears to be standing by his previously declared intention to complete the longest possible term. If he stays in post until January 2026, he will be the longest serving archbishop of Canterbury since Michael Ramsey, who retired in 1974 having occupied Lambeth Palace for a little over 13 years.

Whoever is chosen to replace him will be the 106th person to have held the position since St Augustine of Canterbury was sent from Rome to Kent to convert the Anglo-Saxons in the sixth century. Though the archbishop of Canterbury is the Church of England’s most senior bishop, they are not its supreme head – since the English Reformation, when Henry VIII broke from Rome in 1529-36, that role has been held by the monarch. As well as being bishop of the diocese of Canterbury, with oversight of 327 churches in east Kent, and metropolitan archbishop of the province of Canterbury, which covers the southern two thirds of England, Canterbury must also hold together the fragile coalitions of the Church of England (CofE) and the global Anglican Communion. The archbishop’s powers to do all this are not formal or legislative, but based on soft skills: persuasion, reconciliation, the ability to garner good will; they are no executive leader, like the pope, but “first among equals”.

No smoke will rise from the Sistine Chapel when Welby’s successor is chosen, but the successful candidate must navigate an opaque selection process. Asked in 2002 what the procedure was for replacing the then archbishop, George Carey, a CofE spokesperson comically replied: “I just don’t know.”

Selection is secretive and by committee. Since it was established in the 1970s, the ad-hoc Crown Nominations Commission (CNC) has been responsible for choosing the archbishop of Canterbury. When it is next established, the CNC will be composed of 17 voting members: three representatives from the Canterbury diocese; six members of the General Synod; the Archbishop of York; another bishop elected by the House of Bishops; and, in a change since 2012, five representatives of the global Anglican Communion, which counts 85 million members. The final voting member is the CNC chair, often a public figure, who must be a communicant CofE member, appointed by the prime minister. When the committee was convened in 2012, David Cameron chose the cross-bench life peer Richard Luce, a former Conservative MP and lifelong Anglican, for the role “after taking soundings of senior figures in the Church”.

The CNC will be completed by two non-voting members: the archbishops’ secretary for appointments, one of the most influential positions in the CofE, currently held by Stephen Knott; and the prime minister’s secretary for appointments, presently Jonathan Hellewell. (Hellewell, a former prime minister’s faith adviser and private secretary to the Prince of Wales, was appointed by Boris Johnson in July 2022.) The secretary-general of the Anglican Communion may also sit as a non-voting member.

The influence of No 10 over the process is often overstated. The Mail reported last year that Tory aides were canvassing MPs for a “suitable” replacement for Welby, seeking to create a “head of steam” behind a “less woke” candidate, and the Guardian claimed in 2012 that Conservative MPs were lobbying Cameron “to choose a traditionalist candidate”. But while the prime minister is represented on the CNC, in 2007 Gordon Brown gave up the premier’s prerogative power to choose the archbishop of Canterbury. Previously, the CNC presented Downing Street with two names in order of preference, from which they could choose whom to commend to the monarch, who officially nominates the archbishop – or reject both. It is often said that of the two names the CNC put forward, one would be a wildcard to push the prime minister to opt for the committee’s other, preferred candidate. In 1990 Margaret Thatcher surprised everyone, the story goes, by choosing the outsider, Carey, over the preferred John Habgood, then the archbishop of York, whose supposedly left-wing social views she distrusted.

In the post-Brown era, the CNC submits only one name to the Palace via Downing Street; it may also agree a second choice, to be kept in reserve should the first not be able to take up the post. This has not been viewed as a universally positive development: “Some people feel that it removes a kind of safety valve, that the bishops become more likely to perpetuate existing norms, whereas a lay outsider might go for the more talented exception,” John Milbank, a theologian and professor at the University of Nottingham, told me.

The successful candidate must win the support of two thirds of the CNC, but how exactly certain names come before the committee, and the discernment process by which one rises to the top, is unclear. Some sources suggest the commission quietly canvasses different groups in the CofE for their preferences; others that the appointments secretaries maintain dossiers on prospective leaders – “potential baby bishops”, as Helen King calls them.

In 2012, in a nod to modern ideals of transparency, the vacancy was – perhaps rather pointlessly – advertised in the Church Times. “Any person wishing to comment on the needs of the wider Church or the Diocese of Canterbury, or who wishes to propose candidates” was invited to write to the appointment secretaries. In an interview in 2013, Welby said that as one of the five most senior bishops (he was bishop of Durham before he was translated to Canterbury), he was “told” to apply.

The minimum requirement for Lambeth is to be an Anglican bishop. The archbishop of Canterbury does not have to be a bishop in the Church of England: they could be translated from the Anglican church in Scotland, Ireland or Wales, as with Rowan Williams – or even, theoretically, from the Anglican Communion.

Age is, inevitably, a consideration: received wisdom is that any bishop currently over the age of 62 would be too old to enjoy a reasonable term after Welby’s retirement and before their own. Of the appointments since the Second World War, only one – Donald Coggan in 1975 – was enthroned in his sixties. Of those seven, six served at least ten years; Coggan, at five years two months, was the exception. This considerably reduces the size of the pool: of the 37 serving diocesan bishops excluding Welby, 22 are over 60. The Archbishop of York, Stephen Cottrell, for instance, is widely liked and respected as an evangelist and a good communicator, but at 65 is too old to be anything except a placeholder at Canterbury. Sarah Mullally, a former chief nursing officer and the first female bishop of London, 62, is also likely to be ruled out on this basis.

The overwhelming majority of the occupants of Lambeth Palace over the past 100 years have been privately and Oxbridge educated, and all have been white – but it is possible that some on the CNC will wish to break this pattern. The next archbishop could also, for the first time in history, be a woman, after the General Synod voted to allow female bishops in 2014. “Appointing a woman would not be without controversy,” said Marcus Walker, the rector of Great St Bartholomew’s in central London and a member of the synod. “There might well be a view that it’s too early in having women bishops to do that, which I think would be a pity.” On the other side, there are those for whom being a female would be an “active positive” for a candidate.

Will the CNC feel a certain pressure to consider the external optics of their appointment? For Milbank, this is the wrong approach: “There will be a lot of pressure with some people to appoint a woman or a person of colour, or both. My view is that we should be colour and gender blind; we should appoint the best person. To me, that’s egalitarian.”

[See also: My reckoning with charismatic Christianity]

How might an ambitious bishop – though the nolo episcopari convention forbids them from admitting so publicly, human nature suggests they must exist – ensure their name comes before the commission? The 26 Lords Spiritual have the opportunity to raise their profile in the House of Lords, but political interventions could backfire with those who consider Welby, and before him Rowan Williams, to have been too outspoken. By taking certain leadership roles, such as heading a theological college or chairing the Ministry Council, which advises the House of Bishops on training ministers, a bishop can present themselves as a safe pair of hands.

Those with a greater appetite for risk might take on a role such as lead bishop for the Living in Love and Faith consultation (LFF), a Church-wide effort to “discern a way forward” on the CofE’s stance on identity, sexuality and marriage – as the Bishop of Leicester, Martyn Snow, has done. Snow, who was born in Indonesia where his parents were missionaries, is also chair of the College of Archbishops’ Evangelists. Leading the LFF is an unenviable task, but if Snow can successfully bring all factions of the Church with him through it, he might mark himself out as the kind of leader who can hold together a broad and fractious union.

“You wonder whether taking on some particularly ghastly roles in the Church is a way of saying: ‘Look, I’ve done my service… I’m a good person, I can handle conflict. How about me?’” said King of the Open University.

Alongside Snow, the two names speculated about most often are the Bishop of Norwich, Graham Usher, and the Bishop of Chelmsford, Guli Francis-Dehqani. Usher is, at 53, among the younger bishops. He attended Edinburgh and Cambridge universities, obtaining degrees in ecology and theology, before training for the priesthood. He is particularly strong on the climate, having been the CofE’s lead bishop for the environment since 2021. He has also written two books about spirituality and the natural world, and dedicated his maiden speech in the Lords to the subject. Environmentalism is one of the few issues on which many Anglicans agree, and might also commend him to those who wish to press the Church’s relevance to young people. His diocese, Norwich, includes the royal palace of Sandringham, and Usher, who took part in the coronation as one of the two bishop assistants to Queen Camilla, is said to be friendly with the King.

Francis-Dehqani’s personal story speaks to a different pressure point in our political moment: immigration. The Bishop of Chelmsford, 57, is Iranian-born British and was the first minority-ethnic woman to be ordained a bishop in the UK. Her father was the Anglican bishop of Iran, and her mother was injured in an assassination attempt on him in 1979; her brother was murdered there by Iranian agents the following year. Francis-Dehqani said when she became a bishop in 2017 that this experience, and her family’s subsequent flight from Iran, gave her “a sense of what it is to be on the margins, and the work it takes to find a sense of belonging”. It also, said Walker, gives her a unique, personal understanding of “an Anglican Communion that is in large parts hit by persecution. There would be a real sense that she’s able to speak to the wider Anglican and Christian world.”

“The idea of having a bishop who understands racism and immigration is very important,” said King. “But she’s also a superb bishop, and she tends not to follow the party line. She’s quite outspoken, which I think is a good thing.”

The Anglican priest and assistant editor of UnHerd Giles Fraser told me he is “at Ladbrokes hovering with my £5, equivocating between the Bishop of Norwich and the Bishop of Chelmsford”. He speaks highly of Usher as a “recognisably mainstream Anglican” and a “safe pair of hands”. But his “exciting bet” is Francis-Dehqani: “I think people still remember that extraordinary speech in the House of Lords about Iran and her brother dying… She has something to say, she has a story that’s quite compelling.”

Which of the three front-runners – Snow, Usher or Francis-Dehqani – you consider the most likely winner depends on whether you believe that the “thin pope, fat pope” convention holds. “Since the Second World War there has been an unwritten rule that you have an evangelical followed by a High Church, Anglo-Catholic type,” said Milbank. This “compromise” is said to help hold together a broad church: each side has its turn. Following this pattern, Usher, considered more High Church, would be a natural successor to Welby, who is from an evangelical background. “If the CNC still thinks that rhythm should be maintained, then Usher is the front-runner, and politically you’d be making less of a statement [than with Francis-Dehqani],” said Walker.

Not everyone I spoke to agreed that the CNC is cynical enough to be led by this rhythm, rather than simply choosing the objectively strongest candidate. But there is broad agreement that each new archbishop is different from the last. Fraser correctly predicted Welby’s appointment based on this principle: “He was just so completely unlike Rowan, and just had this sense of being a new start. Francis-Dehqani would absolutely fit that profile of being someone completely different, and actually might excite people.”

Pressure on the Church of England to “excite” has never been greater. According to the 2019 British Social Attitudes survey, the proportion of the British population that identifies as Christian has fallen from two thirds when the survey began in 1983 to just over a third. But the drop in those identifying as Anglican has been far greater – from 40 per cent in 1983 to just 12 per cent in 2018 – and they are now outnumbered by non-denominational Christians (including black Pentecostals), up to 13 per cent from 3 per cent in 1998. Weekly CofE attendance, while rising, remains below pre-pandemic levels, at 1.2 per cent of the population of England, and on average, 20 CofE church buildings are closed each year.

An emphasis on reversing this decline has inevitably given the CofE’s evangelical wing greater prominence. This shift predates Welby, but he is, through his links with the charismatic London mega-church Holy Trinity Brompton (HTB), indelibly associated with it, and evangelicals are considered to have become more dominant during his tenure.

The rise of HTB – which, with its rock-band music and emphasis on evangelism, attracts thousands of young, metropolitan worshippers, many of them influential (the GB News owner Paul Marshall is among its congregants) – contradicts the narrative of an ageing CofE in decline. The Alpha course, which has been taken by more than 24 million people and counts among its celebrity attendees Geri Halliwell, Bear Grylls and, more dubiously, Russell Brand, was set up by its clergy. The HTB model is designed to be replicable: it has through its charity, the Church Revitalisation Trust, planted more than 100 new churches, and many other, similar networks have been made in its image. (The church I attend in north London is part of such a group, whose origins can be traced back to HTB.)

Both Milbank and Walker believe that the dominance of evangelicals has led the episcopate to become less diverse in faith background, meaning there are fewer candidates who would be a marked divergence from Welby. “Recently, a new brand of liberal evangelicals, who are often quite charismatic, like the Archbishop of Canterbury, have assumed much more dominance in the Church at the episcopal level, so I think people are concerned that sort of Buggins’ turn might not apply any more,” said Milbank.

“Under this episcopate, we seem to have lost the idea of balance within the episcopacy,” Walker agreed. “Before, archbishops regardless of their stripe tried to make sure that there was a good balance of evangelical, Catholic, middle of the road; a good balance of those who’d been academics as opposed to those who’d been parish priests. All of that has gone out of the window. There is a heavy skewing in favour of evangelicals, heavy skewing away from parochial ministry… and heavy skewing away from academia. You’ve got quite a monochrome episcopate.”

[See also: The Conservative Party has forgotten its own history]

The Church of England is the established church of the nation, and the archbishop of Canterbury by extension its chief religious voice, its spiritual conscience. Canterbury is an outward-looking role: ecumenical, interfaith and inherently political; the archbishop sits in the House of Lords, and they are expected to speak for the Church on matters they discern to be morally significant.

But the UK is no longer a majority-Christian country – according to the 2021 census, 27.5 million people described themselves as “Christian”, 5.8 million fewer than in the previous census a decade earlier – and the existence of an established religion within it seems to some increasingly incongruous. “The biggest thing that should be on the next archbishop of Canterbury’s agenda – the first, overwhelming thing – is how to reconnect the CofE with the people of England,” said Walker.

The Church is divided over how to arrest its decline. The CofE has, for centuries, operated through a structure of parishes: the nation carved into parcels, each under the care of a parish church – and a vicar – visiting the sick and grieving, keeping the church open for prayer, running foodbanks and other charitable endeavours. Crucially, a parish church serves not just the group of people who frequent its pews, but everyone who lives in its locality. The parish symbolises stability, history and an emphasis on the local in a time of precarity and dislocation.

But there is a strand of thinking that argues the parish structure is no longer the best means of creating thriving places of worship and drawing new people to the Church. A 2021 report to the General Synod titled “Simpler, Humbler, Bolder” stated that while the parish system “is good for serving more settled geographic communities… It is less effective in the networks of contemporary life.” Decline cannot be reversed by repeating the old ways; modernisation, including creative, innovative versions of church, is required to attract younger congregants.

Many new expressions of church – from online-only communities to those that meet in cafés – either operate outside parish structures through Bishops’ Mission Orders, or involve church “revitalisation”, where a team from a church with an engaged, growing congregation takes over leadership of another that is struggling. There have also been instances of parishes being merged, leaving one vicar responsible for multiple churches. In 2021 Walker and several other Church leaders began the Save the Parish movement in protest against what they perceive to be the sidelining and degradation of the parish.

For the theologian John Milbank, “the question of parishes” is the “biggest issue” that will face the incoming archbishop. “The current people in charge very much tend to think people aren’t going to church because the parish structure is out of date… They’ve put an awful lot of money into parallel, non-parish things that are lay-led.” Milbank described the level of bureaucracy in the Church as “staggering”: “If you think of the Anglican Church as being a bit like the Post Office or the police service, and suffering all the same problems, you’re probably not wrong…”

“There has been a restructuring of parochial ministry around a sort of minister model: one focal church, fewer priests on a phone rota kind of distribution,” agreed Walker. “I’m sure a management consultant loves these ideas, as do many people in the Church.” But neither Francis-Dehqani nor Usher is associated with the approach; Snow would be the continuity candidate in this regard.

The word “management” comes up often in conversations about the present Archbishop of Canterbury. When Welby was appointed, there was enthusiasm for his secular professional experience, gained during 11 years in the oil industry. But there is today among some Church leaders and congregants a weariness with reinvention and initiatives – even the belief that the Church has capitulated to market pressures. In reaction, the CNC may seek to appoint an archbishop considered more parochial and pastoral.

“There will be an instinct to move away from the excesses of the previous regime,” said Walker. “In this case it will be managerialism.” Francis-Dehqani is widely seen as parochial, pastoral and not at all bureaucratic. “When not looking at it through the lens of party politics and identity politics, she would in many ways be the most old-school of the bishops. Her priority is making sure the parishes work, resourcing ministry there, supporting clergy and laity, being a pastor bishop.”

“There is a strong feeling within the Church that we don’t want another manager type,” said King. Instead, there is a desire for “someone who’s come from a more traditional route through the Church – they’ve been ordained earlier, they’ve served in parish ministry, they’ve maybe published on pastoral matters, on spirituality, they have a more pastoral feel than a managerial feel… We’ve gone from Rowan Williams, clearly highly academic, a thoughtful, pastoral, priestly sort of leader, to Justin, who has more of a background in the world, a more evangelical background. Does that mean we flip back again? Or can you find someone who is somewhere in between?”

[See also: Justin Welby: “It’s better to be woke than asleep”]

When Justin Welby entered Lambeth Palace in 2013, he was welcomed as a unifier: if he could hold together the disparate parts of himself – oil executive turned priest, the son of alcoholics, educated at Eton – perhaps he could hold together the fractious Church of England, too. A decade later, such hopes seem increasingly naive.

The Church’s preoccupation with questions of sex and gender is alienating to the more conservative worshippers of, say, Nigeria, whose archbishop last year declared that Welby had “begun a second Reformation” by allowing the blessing of gay relationships. Since Welby entered Lambeth, archbishops representing 12 of the 42 Anglican Communion provinces have broken with him. It seems impossible that the next archbishop of Canterbury could continue to move the Church of England in line with the changing social mores of the UK and preserve its global communion.

The Church remains divided over women bishops and same-sex blessings, both of which passed through the General Synod during Welby’s tenure. It is also dealing with the fallout from multiple abuse scandals involving children and vulnerable adults.

Apparently lower in stakes to the secular world but no less existential are divisions over the preservation of the parish and fresh expressions of church. At the heart of this conflict is a question that has long been present in Christian life, on a personal and an institutional level: to what extent can and should the Church reshape itself to remain relevant and appealing in an increasingly multi-faith and secular Britain before it becomes indistinguishable from it?

Against this backdrop, perhaps a more pressing question than who will be the next archbishop of Canterbury is: who would want to be? The principle of nolo episcopari suggests whoever answers “me” should not win the race for Lambeth Palace.

[See also: The rise of cultural Christianity]

This article appears in the 04 Sep 2024 issue of the New Statesman, Starmer under fire