Forty years ago today the constituents of Bermondsey voted in one of fiercest elections in modern history. Campaigning and press coverage of the by-election was vicious, featuring tabloid smears and homophobia. In the end Simon Hughes, the Liberal candidate, won what had been a safe Labour seat with a majority of almost 10,000 and Peter Tatchell, the Labour candidate and now a renowned LGBT and human rights campaigner, suffered a crushing defeat.

It was “the dirtiest, most violent and homophobic election in Britain in the 20th century”, Tatchell says several times when we speak via video call. Tatchell is subdued and a little tired, explaining that he had an accident on his bike a week or so ago, but he remains arrestingly articulate and clear – speaking with a considered, fluent thoughtfulness. He has told his remarkable story many times before.

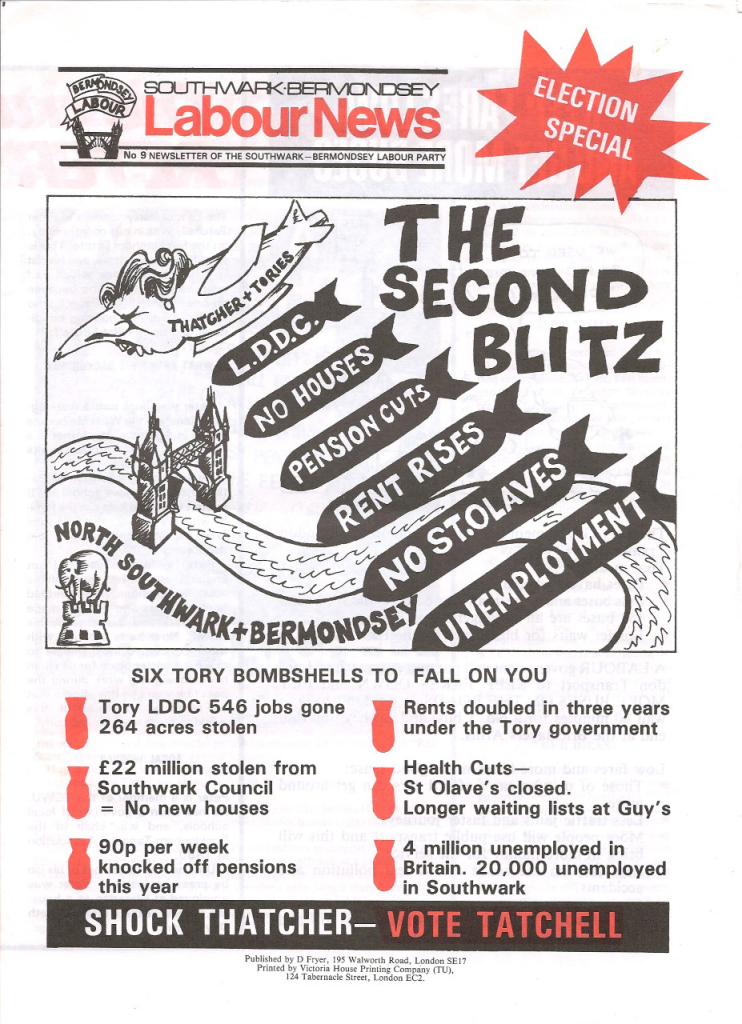

During the 1983 campaign, in southeast London, Tatchell, who was 31 on polling day, was subjected to more than a hundred violent attacks, and rampant homophobia was a key feature of smear campaigns against him. Some of these smears were orchestrated by people within the Labour Party. “The by-election took place in the context of a battle for Labour’s soul between the left and the right of the party,” Tatchell explains. At the time the left, led by Tony Benn, was in the ascendancy and Tatchell says that “right-wing Labour was out to destroy [him] by any fair or foul method”. Tatchell was denied the level of support usually offered to candidates by the Labour executive, which was controlled by the right of the party. He was allocated only 12 support workers to help on the campaign, instead of the usual 80 or more.

The Liberal campaign was accused of taking part in the homophobia as well; some canvassers were seen wearing badges saying “I’ve been kissed by Peter Tatchell”. Hughes, who went on to become deputy leader of the Liberal Democrats and held the seat in its various forms until 2015, has denied deliberately stoking hatred towards Tatchell. He has said, however, that “anything that my colleagues or I added to growing homophobia was unarguably wrong and cannot be justified”. Anti-Tatchell leaflets were distributed, some in the dead of night. One particular leaflet, attacking Tatchell’s sexuality and republicanism by asking “which queen will you vote for?”, listed his phone number and home address. Hughes has denied responsibility for these, saying he assumed the leaflet came from right-wing Labour or an extremist group.

“Despite all this violence, the police refused me 24-hour protection,” Tatchell says, his voice wavering slightly. He recalls the intense fear and the PTSD and night terrors that followed. “It felt like living through a civil war. Every time I stepped outside my flat I was fearful of assault, and even within my flat I didn’t feel safe.”

Now, Tatchell’s defeat looks like a mere blip in a lifetime of activism and politics. “In many respects, not being elected has given me greater freedom and capacity to campaign and change things from the outside,” he says. Since then he has worked on various campaigns fighting for LGBT rights and social justice. Much of his campaigning has involved protests, and he has been arrested multiple times. He attempted citizen’s arrests on Robert Mugabe, the president of Zimbabwe, in 1999 and 2001 over the use of torture against his critics. Tatchell eventually left the Labour Party in 2000, outraged by what he alleged was the “rigging” of the London mayoral elections. Since then he has joined the Green Party and ran as a prospective party candidate in 2007.

[See also: Is Keir Starmer setting himself up for failure?]

Labour selections have long been marked by factional power struggles, but for Bermondsey this was a defining feature. “I was seen as a flag bearer for the left of the party,” says Tatchell. “So right wing Labour MPs targeted me in a bid to discredit the whole left.” The Labour leader, Michael Foot, tried to block Tatchell’s candidacy, despite his grass-roots popularity, because he had written an article that called for non-violent public protests.

The pertinence of Tatchell’s comments today is striking. Keir Starmer has been accused by some of purging the party of its left wing. Just last week the Labour leader said that his predecessor, Jeremy Corbyn, would not be standing as a Labour candidate in the next election. “If you don’t like the changes we’ve made,” he said, “the door is open, and you can leave.” Those supportive of Starmer argue that his interference in candidate selections is necessary to restore stability and electability to a party beset by allegations of toxic factionalism and anti-Semitism. But conflict seems to be coming; some MPs say Starmer’s involvement in the selection process is beyond what has happened before.

I ask Tatchell his view. “I feel incredibly disheartened that the Labour leadership is using authoritarian methods to block left-wing candidates that it disagrees with, even when they have strong local roots and lots of support both within the party and in the wider community,” he says. “That is not democratic. It signals that Labour doesn’t take democracy seriously.”

I wonder if Tatchell sees parallels between the attacks on his sexuality – “the worst public vilification of a gay public figure since Oscar Wilde,” he says – and the politicisation of transgender rights. “The way in which my sexuality was demonised in the Bermondsey election has echoes today in the way in which trans people’s gender identity is being vilified,” he says. But the debate was of a different calibre. The Conservatives face accusations of using transgender rights as a political football to stoke divisions in Labour, which is split over female-only safe spaces and gender self-identification. But the level of violent homophobia that Tatchell experienced in the Eighties is a different proposition. “Politics is bad today, but nothing on the scale of Bermondsey,” Tatchell says.

Despite the violence and the left’s defeat, Tatchell believes the by-election holds valuable lessons for Labour. In the 1920s and 30s, the Bermondsey Constituency Labour Party had over 3,000 members and ran its own community groups. They “supported working mothers, had a municipal health service that pre-dated the NHS, organised sporting and cultural events, and went door to door to fix people’s houses. Back then, Labour was seen as the voice of the community and social life in the community revolved around the Labour Party.”

Now, Tatchell believes Labour is too far removed from its roots: barely engaging with the heart of local communities, too Westminster-focused, leaving people behind. “Labour seems to look at winning power through focus groups, spin doctors and public relations. It often ignores it own members and the importance of year-round engagement with local communities.”

Is there a future for the left in the Labour Party? Tatchell believes so. “Some people on the left have the strategy of capturing positions of power within the Labour Party. That’s not the way to go. We’ve got to start from grassroots organising and rebuild the Labour Party from the bottom up.”

Read more:

Keir Starmer essay: This is what I believe

Margaret Hodge: Confronting anti-Semitism in Labour was harder than fighting the BNP

Is Keir Starmer setting himself up for failure?