Hannah Barnes: Amanda Pritchard has portrayed her resignation as voluntary. Do you think that’s necessarily the case?

Phil Whitaker: I wouldn’t like to comment, but I think if she hadn’t gone, she would had to have been ousted, I’m afraid.

We had these quite strong criticisms from the House of Commons committees, saying those at the top of NHS England “do not seem to have ideas or the drive to match the level of change required”. Is that something you’d agree with?

I think it even goes more deeply than that, actually. The crisis that we see around us at the moment has been quite a few years in the making. I know we’re talking about Amanda Pritchard, but this dates back even further and it speaks really to what we might call a groupthink or a culture within NHS England, and also I would say within the Department of Health and Social Care, who really don’t actually understand how a functioning health service should be structured and put together.

In what way?

Essentially the NHS, for most of its history, has had a good balance between generalism and specialism. I’m a general practitioner. I can deal with most of my patients’ concerns and difficulties, and then maybe about 10 per cent of caseload that I deal with, I pass on to specialists. And the people that I pass on, they need that specialist care.

That’s how the health service has been run for 60 years of its existence. What we’ve seen since 2010, and it’s accelerated since 2015, is an erosion of the generalist layer in the health service. Since 2010, the proportion of the population over 65 – the highest users of the health service – they’ve gone up about 30 per cent or so. The numbers of hospital doctors, specialists, have gone up by more than that, about 48 per cent. The number of general practitioners, people like me, have actually gone down, 12 per cent now. So instead of the generalist numbers rising to meet the demand, they’ve actually been declining.

Within the NHS, this is one of the big problems that we’ve got now, that the generalist layer has disappeared, or it’s been hugely eroded. And the thing that everybody needs to appreciate is if you’ve got a health problem and you can’t get care from your GP, that health need doesn’t just disappear. You end up going into secondary care via the ambulance service or A&E.

So what we’ve seen with this erosion of the generalist capacity in the health service is that more and more activity is going into the hospital sector. It’s more expensive and it puts pressure on the hospital services. That’s why we’re seeing the waiting times and the A&E problems that we’re seeing. And who’s responsible for that? The people who’ve been running the health service. And that is kind of why Amanda Pritchard had to go, and why actually there needs to be a big clear out in NHS England and the Department of Health and Social Care.

You’re talking as a GP, obviously, and you’re saying that the balance between generalism and specialism is not right. But even today we have job adverts for a doctor to work solely in the corridor of the hospital attending to the elderly and the frail. Despite that huge increase that you mentioned in hospital staff and the diminishing number of GPs. The hospitals are in a dire state, aren’t they?

They are, but I think what you need to understand about A&E is it’s effectively like the canary in the coal mine. The crisis in A&E is telling us about the wider system. Most people are familiar with the idea of the “back door” – so social care. The crisis there is meaning that a lot of people are staying in hospital when they’re medically fit to go, but they’ve got nowhere to go on to with support. There’s also the “front door” problem, which is primary care, and that’s been eroded over the last 14, 15 years. So people are washing up in the A&E departments, and then the hospital itself can’t get people discharged into the community, and A&E is in the middle there, squeezed from both sides, and overflowing into the corridors.

Would more GPs help that?

I’m going to resist the idea that there’s a silver bullet, because there isn’t. But just a little personal anecdote: my own mother in her eighties was in hospital having collapsed on New Year’s Day, 2023. She spent 36 hours on a hard trolley in a corridor in a hospital in Kent, and I stayed with her all through that time because there weren’t sufficient staff to actually look after her, or indeed many of the other people around. And I helped look after some of the people around her, and I talked to and listened to many of the stories there now.

There were some people there who needed to be there – a diabetic with a very serious complication of diabetes, somebody with a major head injury. But there were lots and lots of patients who, I know from the stretch of my career, having been a GP over 30 years, once upon a time, people like me would have been looking after them at home. The erosion of the capacity of general practice has meant that they’re just not being looked after at home. There isn’t the capacity to do so, and so they’re winding up in A&E. It’s A&E that’s signalling the distress, but the problems are actually elsewhere.

We’re expecting in May the ten-year plan to overhaul the NHS and deliver the Prime Minister’s pledge to make it “fit for the future”. If you could pick one thing, would you like to see in that plan?

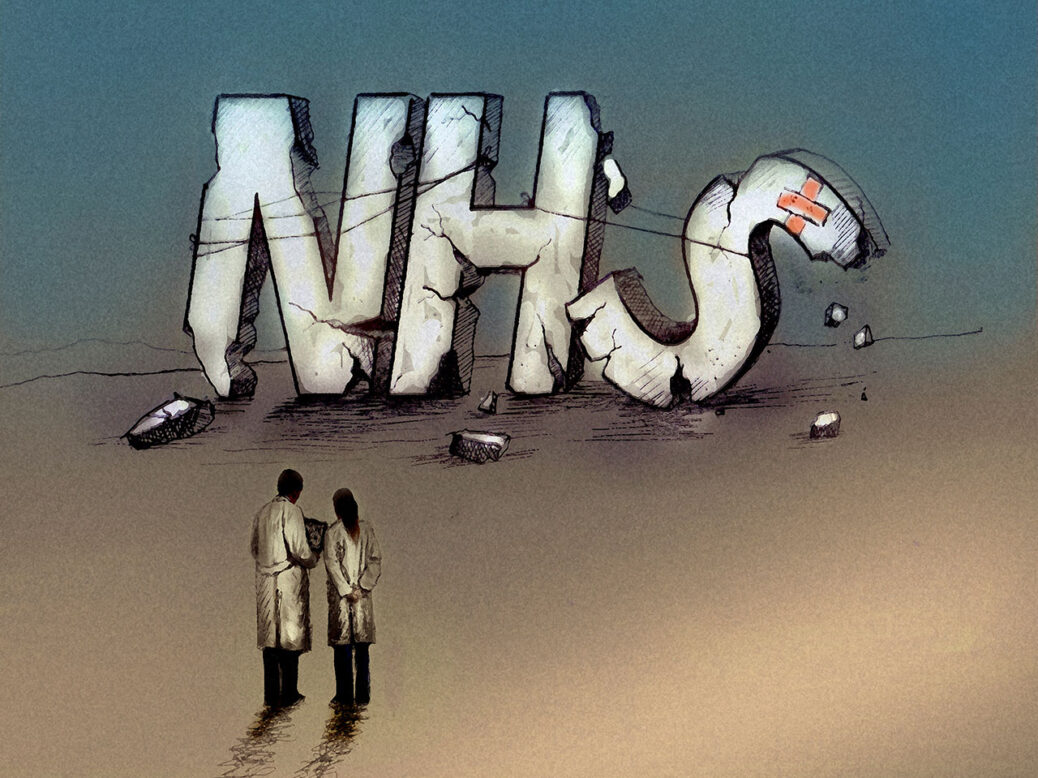

With the proviso that there’s no one silver bullet, essentially the key thing is a target over that ten years to bring GP list sizes down, I would argue, to something like 1,200 patients per GP. That’s about half of what it is at the moment. That’s going to require a sustained recruitment and retention effort in general practice, but it can be done. It’s been done before. If you get that sort of level of patients per GP, we will be able to look after people outside in the community and take a lot of the work that’s currently in the hospital sector out. So the single thing would be a huge focus on restoring general practice and strengthening that. It’s the foundations upon which everything else rests. And if the foundations are crumbled and fallen down, the whole building is teetering and it’s going to go.

[See also: Can Kim Leadbeater justify her assisted dying bill?]