The UK is facing a decisive decade of economic change that the country is neither used to, nor prepared for. It’s time to rebuild our approach to economic success in the light of those shifts to the jobs we do, the firms we work for and the places in which we live. Simply muddling through – by far the most likely outcome – risks leaving us diminished and divided as a nation.

The vaccine roll-out means minds are now turning to how to make a success of the recovery to come, even as we grapple with the transmissibility of the Indian variant. The lasting impacts of the pandemic are highly uncertain, but it’s safe to say we won’t just return to the pre-Covid world. Online shopping, for example, is here to stay. Greater home working means more lifestyle choices for professionals, but forces lower earners who rely on their spending to find new jobs in new places.

These trends been widely discussed, but focusing just on the pandemic’s impact misses the scale of the change we’re facing. As well as recovering from Covid-19, this decade will see us emerging from the EU, urgently transitioning towards a net-zero future, while adapting to technological and demographic shifts. The former in particular means higher trade costs for firms, but newfound freedoms for policymakers. It will see some of our most productive firms shrink, while others grow.

Action on decarbonisation is urgent: we need to go from installing almost no heat pumps each year, to installing 3,000 every single day by 2030. The opportunities are big, but the short-term costs are significant. Almost all of the painful political decisions about net zero are still to come.

Meanwhile, this decade is the fastest for our demographic transition in the first half of this century.

All these changes will be happening in concert rather than isolation, interacting with each other and policy makers’ attempts to manage them.

Some will be relaxed about this, arguing the UK is used to accelerating change, with our flexible economy adept at managing what would otherwise be difficult adjustments. The first premise is simply wrong, and the second questionable.

In reality, the first two decades of 21st-century Britain have actually seen falling or flat economic dynamism. The shift of workers between sectors in the 2010s was at its lowest level since the 1930s.

And when economic change has taken place, we struggled to make it inclusive. 1980s deindustrialisation saw the government of the day embrace change, with fast rising incomes for the top and middle. But this was combined with very high costs for people and places losing out. Long-term unemployment more than trebled in the early 1980s and some areas – including Wansbeck and Liverpool – lost over a fifth of their jobs. Four decades on the country is still living with the fallout.

Complacency about change is therefore unwise. It’s true that the UK does start with considerable strengths: record employment pre-pandemic, excellent high-value services (demonstrated in life sciences recently), and a political consensus over decarbonisation. But we have major weaknesses too, from the slowest productivity growth for over 120 years in the past decade to higher inequality than any EU country save Bulgaria.

The poorest households have seen next to no income growth for the past 15 years and regional productivity gaps remain too large: GDP per capita in London is 2.4 times higher than it is in Doncaster.

Wrestling with this change and addressing these weaknesses is the task we face in the 2020s. It is easy to imagine a future in which the economy “levels down”, as the young and low-paid suffer from the pandemic, uncertainty suppresses investment and opportunities to lead in new-low carbon industries are missed. Past problems might be overlooked, and future challenges addressed haphazardly. Rather than redesign the country’s economic strategy, we may choose to muddle through.

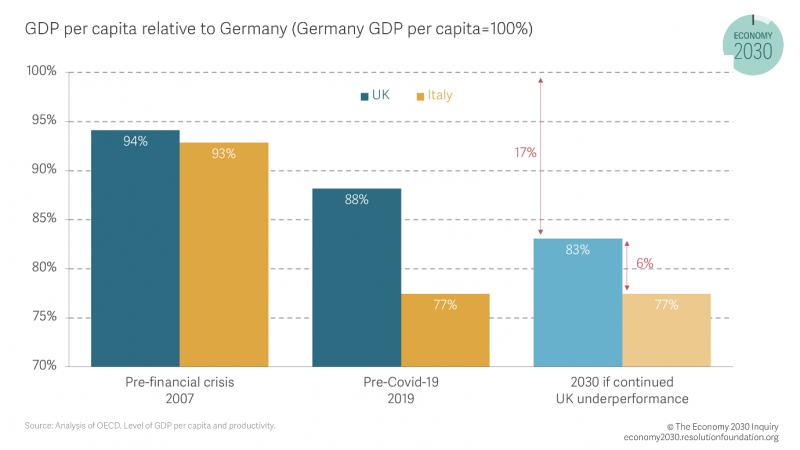

This risks a prolonged era of relative decline. Countries’ relative economic performance can – and do – change. Italy was as prosperous as Germany in the 1990s but has seen no GDP per capita growth since. The UK itself has fallen further behind Germany recently. If that continues in the 2020s, we will end this decade with GDP per capita much closer to that of Italy than Germany.

Being Italy without the food and weather should not be our aim. This danger goes far beyond economics – we have seen the social and political risks of stagnant incomes, especially when twinned with high inequality.

Alternatively, the scale of change facing the country could act as an impetus for major reform, with a renewed vision for how we successfully compete in the world, ensure widespread good employment and seize the opportunities that decarbonisation may bring. The end point would be a more prosperous, fairer, greener and healthier nation.

While the UK government currently has many slogans about what it is trying to achieve, from “Build Back Better” to “Levelling Up”, neither it nor any major political party has an economic plan for achieving these objectives. Slogans actually obscure the trade-offs involved, exaggerate policymakers’ agency, and pretend choices about the UK’s competitive strengths can ignore the reality of a world economy being shaped by China, the EU and the US.

The Resolution Foundation’s Economy 2030 Inquiry, launched today, aims to wrestle with that reality – driving a two-year national conversation on the future of the UK economy, and bridging rigorous research, public involvement and concrete proposals for change.

One way or another, whether by omission or commission, the 2020s will be the decisive decade that will determine the UK’s trajectory into mid-21st century. We need to make a success of it.