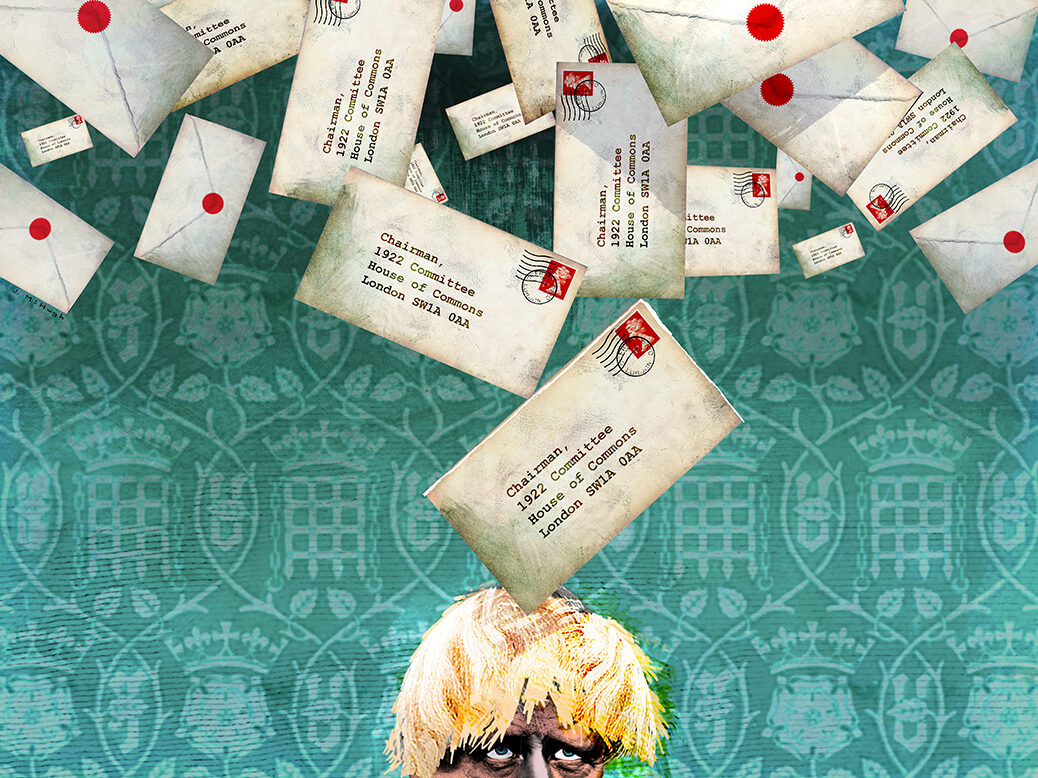

It might not be long before Boris Johnson sends in a letter to Graham Brady, chair of the 1922 committee of Tory MPs, to demand that Boris Johnson be subject to a vote of no confidence. Johnson is hardly likely to chastise himself for creating the impression that the Conservative Party no longer respects British institutions. He might, though, conclude that if a vote of no confidence is going to come, it might as well happen sooner rather than later.

For months now, Conservative MPs have pretended to themselves that they were on the threshold of changing leader. Trigger points have been variously set and abandoned. First they were all waiting for Sue Gray’s report, which was then delayed. The Prime Minister was fined by the Metropolitan Police instead but that was not thought sufficient pretext for action. Then they were all waiting for the local elections, which came and went with poor results for the Tory party but more indecision on the leadership question. Gray has now reported and, though in the aftermath there was a trickle of new rebels, the majority of MPs are still waiting, Micawber-like.

The Prime Minister and his team had assumed that, with parliament not in session, the appetite for plotting would abate. But a mixture of constituency pressure and WhatsApp scheming has made that a fond hope. Dispersed into the country, Conservative MPs are discovering for themselves what every opinion poll for weeks has also been telling them – that Johnson’s lockdown shenanigans are going to cost them their seats. They then take to the instant communication channels and embolden themselves by talking to other MPs who are finding the same where they are. A Prime Minister whose only claim on the loyalty of many of them is that he is a winner has lost his golden touch. If Johnson is not seen by his team as a winner he is in trouble because he has no reserve of affection to draw on.

People close to the action assert that a confidence vote is now a matter of when rather than if. Unless something significant changes in the meantime, though, Johnson is more likely to win than lose any such vote. All the Tory prime ministers of recent memory who have faced a confidence vote of their MPs went on to win. In November 1990, Margaret Thatcher beat Michael Heseltine by 204 votes to 152, only four votes short of the 15 per cent margin of victory that was then required in the first ballot. In July 1995, after years of acrimony over the Maastricht Treaty and the future of the European Union, John Major forced and won a leadership contest in which he beat John Redwood by 218 votes to 89. In December 2018, Theresa May won a confidence vote by 200 votes to 117. The payroll vote – all the ministers who owe their careers to the favour of the prime minister – came in for her, as it had come in for Thatcher and Major.

[See also: The Conservative Party is lost]

Yet none of them was a winner for long. Thatcher was perfectly entitled, as the winner on the first vote, to enter the second round, but she was persuaded not to do so. Major stumbled on to the 1997 general election at which his party was soundly thrashed. May’s victory was followed by the Tories’ humiliating defeat in the European elections (they finished fifth with 8.8 per cent of the vote) and she soon agreed to set a date for her departure.

There are two lessons for the current moment in these examples. The first is to watch the percentage. Thatcher won 55 per cent of the vote, Major 66 per cent and May 63 per cent. Major was deemed to have won and survived the process. Thatcher and May’s victories were considered defeats in disguise, and they were soon gone. Advocates of other possible candidates in the field are already putting it about that 63 per cent is the minimum threshold of acceptable success. If Johnson dips under the percentage of the vote gained by May, they argue, then surely he has to depart.

The second lesson, though, complements the first. None of the previous Conservative leaders simply packed up and left. The vote itself never did the trick. Thatcher declined to enter the second ballot because most of her cabinet told her in a series of private meetings that she no longer had their support. Major was, in due course, thrown out by the electorate. May was forced out because it became clear that she too had lost the trust of her most senior colleagues. In other words, back-bench MPs can take to the airwaves to voice their dissatisfaction all they like, but it’s not in their hands. All their noise can do is to provide a signal.

Let us imagine that, this time, we have more than the usual bluster. Suppose there is a vote of no confidence and that Johnson wins it and takes precisely 62 per cent of the vote. Then what? Johnson himself will not give way. A victory by a single vote will do for him. Echoing Thatcher, expect him, in those circumstances, to fight on, to fight to win. Either a cabal of senior colleagues – led by a Rishi Sunak or a Michael Gove – tells him to leave or Johnson will stagger on to meet the electorate. MPs are on the news today but this is not about them. Eventually this pathetic spectacle will have to be put to an end by those who actually wield the power.

[See also: Tony Blair’s new centrist project shows he and his acolytes have learnt nothing]

This article appears in the 01 Jun 2022 issue of the New Statesman, Platinum Jubilee Special