Asked by a survey or pollster whether the earth is being run by giant reptiles wearing human skins, around 4 per cent of people will reply that, yes, the earth and its governments are indeed being run by giant reptiles wearing human skins. They won’t all say it for the same reason – some will be crazy, some will be trolling, some will have pressed the wrong button – but nonetheless, about 4 per cent of respondents to any poll are liable to give the stupid answer and so can probably be discounted. This is the concept known as Lizardman’s Constant, invented by Scott Alexander of Slate Star Codex.

I mention this because, according to today’s polling by Professor John Curtice and NatCen, only around 6 per cent of the electorate believe Theresa May has secured a good Brexit deal. The theory of Lizardman’s Constant must raise some questions about exactly how many of those guys really, actually mean it.

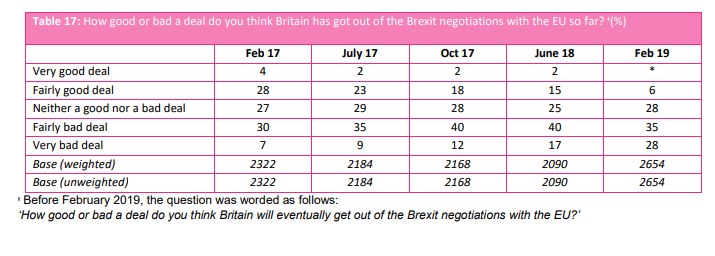

It’s worth noting, too, that that headline figure actually puts a positive spin on the polling. Those 6 per cent are people who say that Britain has negotiated a “fairly good deal”. Back in February 2017, when that question still used the future tense, that number was 28.

But there’s also an option to say Britain would negotiate/has negotiated a “very good” deal. At its peak that was just 4 per cent. Now, according to the data, it’s “*”. I don’t know how many people * means. My guess is that it isn’t many.

Don’t ask me to explain how the apparent failure to get anyone, at all, to say Theresa May has negotiated a very good Brexit deal fits with the Lizardman Constant theory because I don’t know. But the fact that you can get people to say the world is run by lizards, but not that Theresa May has been good at her job, does give pause for thought.

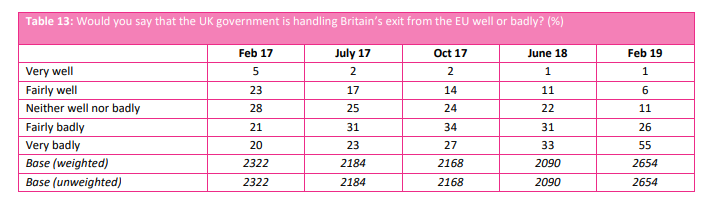

These are not the only numbers in the NatCen report that should concern the government. This table shows changing views on how well our leaders are handling the Brexit process. Spoiler alert: people increasingly think the answer is “not very”.

Two years ago, 28 per cent of people thought it was going well, while 41 per cent thought it was going badly. That would be rubbish enough, except that those figures are now 7 per cent and 81 per cent respectively, making February 2017 look like a golden age for Theresa May’s premiership. At the same time, the number of people who don’t have a settled view has plummeted. This does not feel like a good sign.

Then there’s this: how would you vote in another referendum? In September 2016, Remain already had a five-point lead; but the same was true of some of the polls before the referendum, and look how that ended up, so five points is perhaps not that meaningful a gap. For the next year or so, that lead wobbled about between three and nine points. By last June it had widened to 16. As of last month, the gap was 20 points.

There’s probably a limit to how much comfort pro-Europeans can take from this in itself: that Remain is on 55 per cent still means that nearly half the electorate still don’t think they’d vote to stay in the EU. But then, there’s this:

The number of people on NatCen’s panel who say they voted Leave in 2016 is falling. They’re not now claiming they voted Remain: they’re just saying they didn’t vote. It brings to mind polling around the Iraq War, which was mystifyingly popular at the time, but which people soon forgot ever having supported.

Actually – this paragraph is a clarification, added after this post was published – that’s not quite fair. Anthony Wells of YouGov has been in touch to point out that the panel members’ “reported referendum vote” were taken once, when they first signed up. The fall in the reported leave vote therefore means they’re dropping out of the survey for other reasons. We can speculate on what those reasons are – but it’s not immediately obvious what explanation there could be for the fall in the Leave vote that says good things about Leave support.

All this, concludes Curtice, is “enough to raise doubts about whether, two and half years after the original ballot, leaving the EU necessarily continues to represent the view of a majority of the British public”.

Will any of this make any difference? In the short term, the answer is almost certainly no. As with the petition to revoke Article 50, and the mass march on the streets of London last weekend, Leave-supporters will almost certainly dismiss polling by pointing out that we had a much bigger poll on 23 June 2016, and that 17.4 million people voted Leave. Perhaps a new referendum would go the other way, now – but we still aren’t likely to have one, and neither of the major parties of government is going to stand on an unambiguously anti-Brexit ticket any time soon.

More than that, for all Theresa May’s talk of the will of the people, her over-riding concern throughout this process has actually been the will of the Conservative party, and her successor will almost certainly feel the same. What the people actually think is not likely to come into it.

In the longer term, though, as with the 2003 anti-war movements, the pro-European energy unleashed by the referendum could well start to affect British politics in unexpected ways. In some ways, it already is: I very much doubt that persuading several hundred thousand people to march through London waving EU flags was ever on Nigel Farage’s to do list.

And if the public mood really is changing, our leaders may soon find that a narrow, three-year-old referendum result is not enough to defend them from the wrath of the electorate.