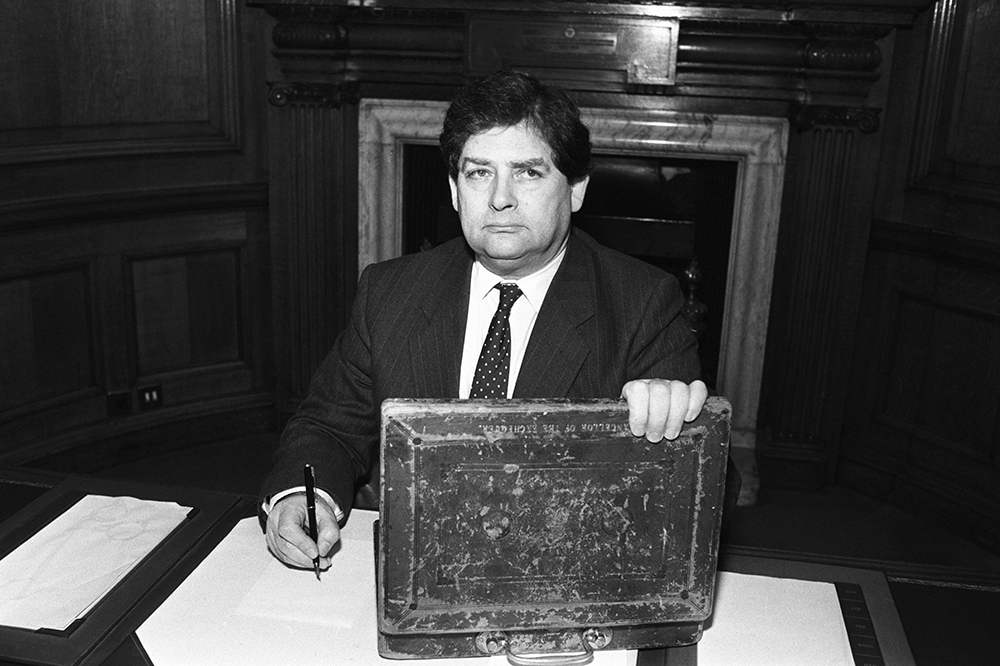

Conservative tributes to Nigel Lawson, who has died aged 91, have focused on the former chancellor’s towering intellect and his defining influence on British politics. They have also served to highlight how recent Tory vintages lack these qualities.

Even ideological opponents have been forced to concede that Lawson was a powerhouse. Of the more than two dozen men who have served as chancellor since 1945, Lawson’s six-year tenure was one of the most impactful. He unleashed the “big bang” of market deregulation in the City of London in 1986, and not only reduced taxes but reformed them – expanding VAT and stamp duty, while cutting the top rate of income tax from 60 per cent to 40 per cent and raising thresholds.

He married this with a broader vision of “popular capitalism”. Combined with the privatisation of much of British industry, Lawson sought to turn ordinary people into the propertied – not just workers in the economy, but owners of it too. Though the Lawson boom ultimately ended in bust, it delivered the economic growth that Margaret Thatcher craved as well as a landslide election victory for the Conservatives in 1987 (with more seats than they have ever won since).

[See also: Are social conservatives the future of British politics?]

At the heart of this success were Lawson’s intellect and vision. While many politicians seek power and are unsure of what to do with it, Lawson was deeply invested in policy. He had a profound understanding of economics and was able to channel this into action. Perhaps only Gordon Brown has rivalled him since. But beyond this, he had a deep sense of the world he was striving towards.

In Lawson’s speeches, he not only name-checks conservative thinkers but is deeply familiar with their arguments. He sat at the intellectual heart of Thatcher’s government, imbuing it with the spirit of Milton Friedman and Friedrich Hayek and understanding how to adapt this to the party of Edmund Burke. He was able to develop a form of conservatism for the challenges of the 1970s and 1980s, rather than relying on repetition of his forebears or chasing the trends of the daily news cycle. Like many of those in Thatcher’s cabinet, he was perhaps informed by his eastern European Jewish heritage – a suspicion of the big state not simply because it meant higher taxes, but because of its power to control and kill, whether run by tsars, Nazis or socialists.

Lawson offered a philosophical depth that recent Tory governments have lacked. Often the party has seemed to seek power without a plan of what to do with it – listing between fashions as leaders come and go. No one in recent Tory generations has matched Lawson. While many are conventionally smart, and some, like Liz Truss, sincerely ideological, they have lacked the curiosity and depth that allowed Lawson to burst through existing orthodoxy and craft something new in its place.

There are many who will disagree with Lawson’s free-market vision and his policies. His later embrace of climate scepticism will be a more contentious part of his legacy, and perhaps shows the danger of too much intellectual certainty. But as the Tories mourn Lawson, they would be wise to remember not just what he did, but what he represented. Rather than merely emulating his tax cuts and spending cuts, they should strive to mirror Lawson’s deep philosophical understanding, vision and pragmatism.

[See also: The uncertain future of the Tory party]