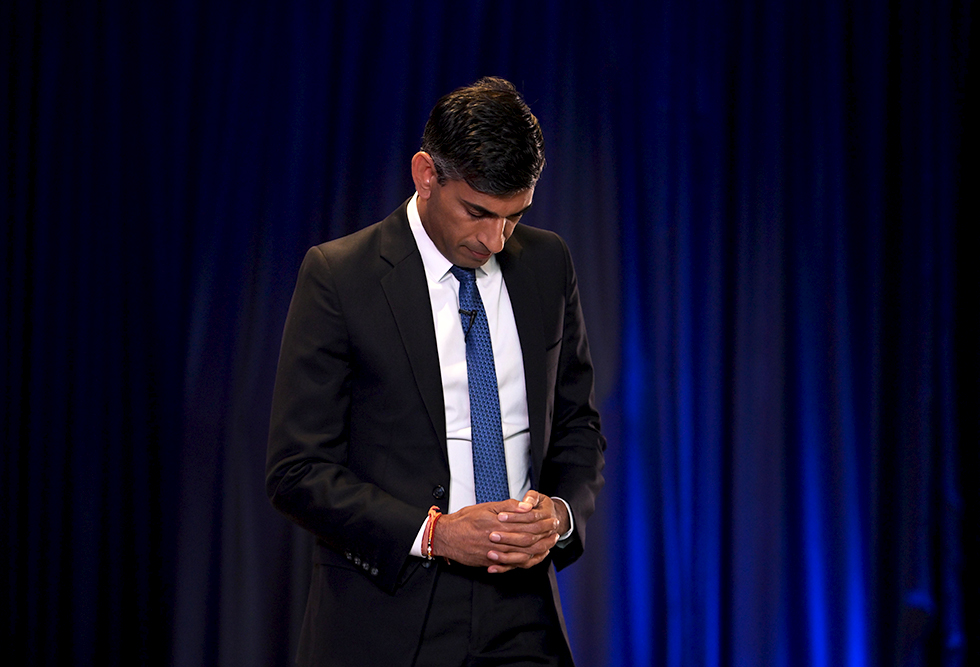

Rishi Sunak has released his tax return. At first glance, you may think it simply shows a rich man paying an awful lot of tax.

Over the three most recent tax years he earned £4.766m and paid £1.053m in tax. Fair play to him, eh. But look closer and the Prime Minister’s tax return exposes the topsy-turvy nature of the UK’s tax system. Last year he paid an effective tax rate of 22 per cent on an income of nearly £2m.