No political party can be at all content when its most famous member works as vice-president for global affairs and communication for Facebook. There is no question that Nick Clegg remains the most powerful Liberal Democrat in the land, even from a base in Silicon Valley. There are two parts to this claim. One is that Facebook clearly matters; the other is that the Liberal Democrats don’t.

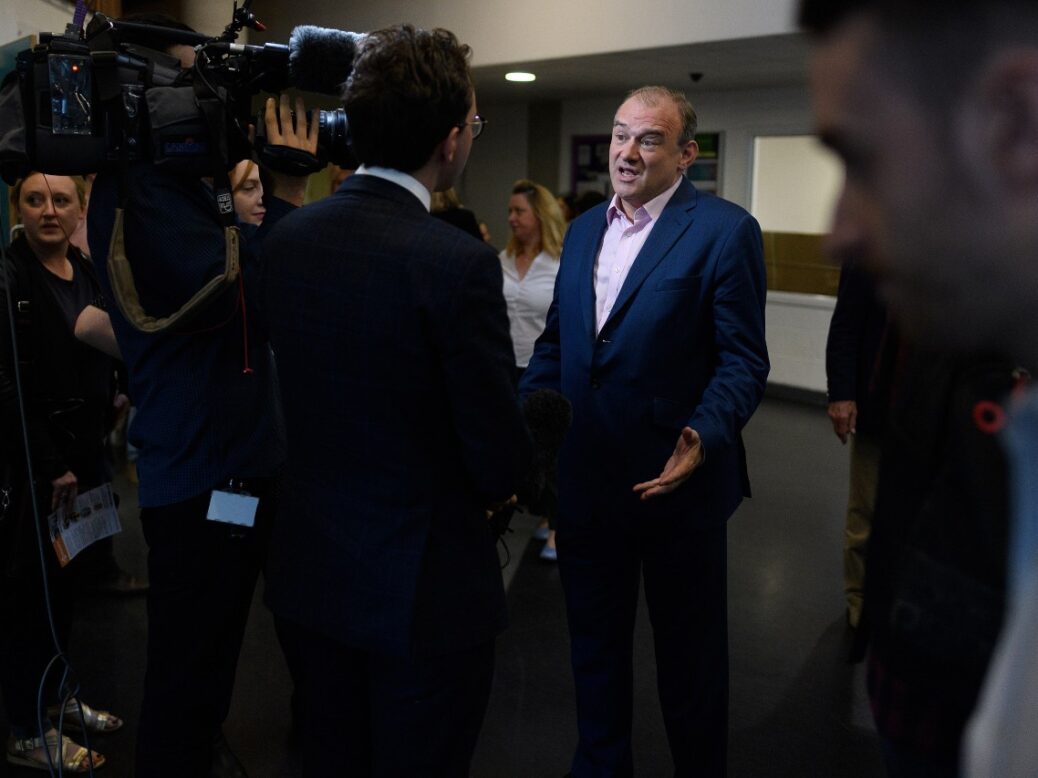

Clegg’s decision in 2010 to take his party into government in coalition with the Conservative Party bequeathed to his successors a terrible, perhaps insoluble, strategic dilemma. Ed Davey is now the fourth leader in six years – after Tim Farron, Vince Cable and Jo Swinson – to wrestle with the consequences. If the Liberal Democrats – after being chewed up electorally by association with the coalition – are no longer prepared to do business with the Tories, that leaves them with two options. They have either given up on being a part of central government for good, or they have become, in effect, a subsidiary of the Labour Party.

The omens for the party are not promising. In the stubborn national polls the Liberal Democrats are struggling to get into double figures. It is not obvious to what question the party is the answer. The recent surge in independent candidates at local elections should be a source of serious anxiety.

[See also: Can the Liberal Democrats now destroy the Conservatives’ “Blue Wall”?]

In 2017 there were 1,572 elected independent councillors across England and Wales. In 2019 there was a big rise to 2,150, which amounts to around 13 per cent of all councillors. There are 32 councils led by an independent and a further 34 in which independents or smaller parties are part of the administration. The trend is turning up in by-elections too. In May’s Hartlepool by-election, Samantha Lee, a businesswoman with no political experience, stood as an independent and beat the Liberal Democrats to third place. In the Batley and Spen by-election in July, the decision of Paul Halloran, of the Heavy Woollen District Independents, not to stand was probably pivotal in Labour’s narrow win.

This is bad news for a third party which ought to be the repository of all those who vote “none of the above”. Paddy Ashdown used to be very good at getting above the political fray, posing effectively as a neutral figure for whom anyone tired of politics as usual could vote. That explains the oddity that there were always quite a lot of voters who would switch from Ukip to the Liberal Democrats. It wasn’t a vote about Europe. It was the politics of “none of the above”. If the Liberal Democrats lose that mantle, then they are truly in trouble.

The independents are becoming the parties of local complaints about building developments. It is not merely coincidental that the high point of independent councillors, in the mid-1970s, was also a very low point in the fortunes of the Liberal Democrats.

This is a strategic problem, but it is one made worse by the party being so insipid. Under Davey, the Liberal Democrats have all but disappeared. It’s hard to recall an intriguing position the party has taken on anything lately. The only advantage of being a small party is that it is a licence to be bold. A party seeking to attract 40 per cent of the electorate has to hedge its bets, for fear that one flank of its political coalition will be repulsed by positions that are attractive to the other flank. A party polling between 5 and 9 per cent does not face this problem. It can paint in a riot of vivid colours, but the Liberal Democrats have been so uniquely yellow.

[See also: What the Liberal Democrats are planning in the “Blue Wall”]

Party advocates knock out their denunciations of the Tories, which are dispiritingly routine. It was possible to strike a different, more liberal line on Covid (not my own preference but a viable position) but instead the Liberal Democrats took exactly the view offered by Labour. Indeed, that has become something of a character trait. It is difficult to find much to distinguish the opposition positions adopted by the Liberal Democrats from those of Labour. The strategic dilemma is being resolved in silence. The absence of boldness will seem to all observers like a coded plea to cooperate with Labour.

There is, of course, a lot to be said for electoral cooperation with Labour. In an electoral system that offers an excessive reward to a minority winner, it makes no sense for two opposition parties to take votes from one another. But it does not follow from the logic of electoral alliance that the Liberal Democrats should set themselves up as an offshoot of the Labour Party. On the contrary, they have a much better chance of taking votes from the Conservatives, and thereby doing the nation a favour, if they define a distinctive character.

In the upside-down politics after Brexit, this is easy enough to do. Brexit itself is an opportunity for clarity. I would not myself vote for a party dedicated to taking Britain back into the European Union but plenty of people would. An unapologetically pro-European line would also be a signal to the sort of people the Liberal Democrats were seeking. Professional, liberal, relatively wealthy, cosmopolitan and comfortable with diversity. While the two larger parties are pointed skew-whiff at the sensibilities of the Red Wall electorate, there is a large and growing body of people wondering who speaks for them.

A good liberal of a former vintage, John Maynard Keynes, once complained about the “watery Labour men” who prevented the emergence of a truly liberal wing to the people’s party. Labour has never been a liberal party but it is a surprise to see that the Liberal Democrats aren’t either. There is a constituency of cosmopolitan former Conservatives who have become too liberal for their own party. An independent Liberal Democrat party could win them over and win itself the right, or at least the invitation, to work with Labour.

[See also: Why a progressive alliance is an electoral fantasy]

This article appears in the 10 Sep 2021 issue of the New Statesman, Labour's lost future