It is likely that at some point in your life – probably the part that involved cling-filmed jam sandwiches and lifting school chairs on to desks at the end of the day – someone has come up to you and said: “The word ‘gullible’ is not in the dictionary.”

If you have ever fallen for this trick by frantically turning the pages of the Oxford English Dictionary, you will know there is little worse than the joy of being right (“Ha! See!”) followed by the sinking feeling of being wrong (“You’re so gullible!”). It is not fun to be fooled, and this sensation is now being felt by social media users across the internet, as they gleefully share stories that align with their political beliefs before being taken down by two, ubiquitous little words: “fake news”.

Naturally, if you’re an esteemed reader of the New Statesman, you will never have felt this sensation. Fake news, we’ve been told, is an exclusive problem of gullible, stupid, right-wing fanatics. While it is true that many fake news outlets, particularly those designed by Russian propagandists, did target right-wing audiences before the US presidential election, we have been foolish in assuming that the left has not been infected by this epidemic.

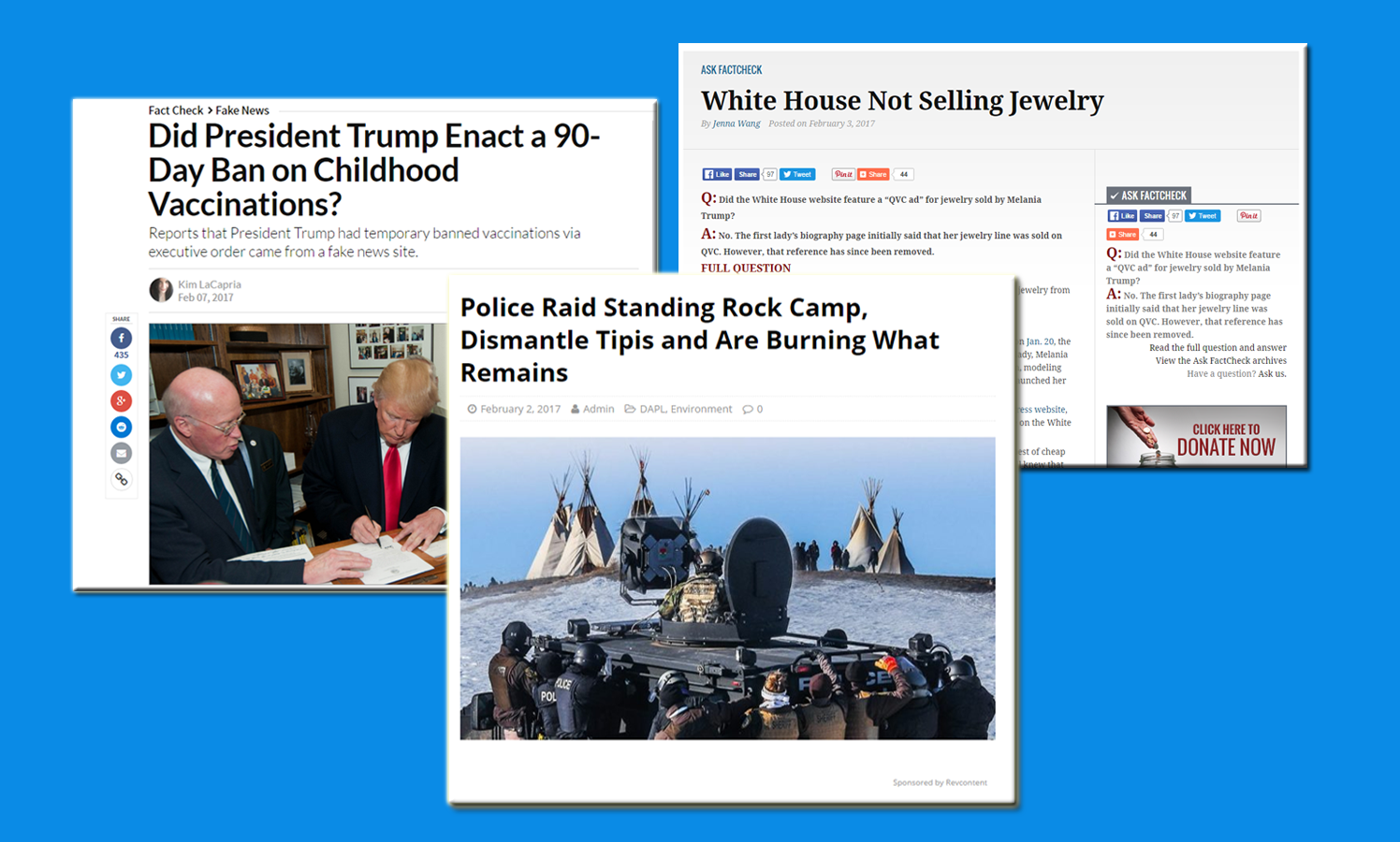

On 30 January, more than a thousand people retweeted a claim that Donald Trump was rewriting the Bill of Rights to include references to “citizens” instead of “persons”. On 31 January, 43,000 people shared the news that the cost of providing security for Melania Trump in New York was double the annual budget for the National Endowment for the Arts. On the same day, just over 51,000 people shared a picture of a young boy handcuffed at Dulles Airport after Trump’s “Muslim ban”. Also in January, stories circulated claiming that Trump plans to make being transgender illegal, that he’d changed the name of Black History Month to “African-American History Month”, and that he’d signed an executive order declaring climate change an immediate threat. All of these stories were either outright false or completely unproven.

Left-wing fake news, however, isn’t an exclusively post-US-election problem. Kim LaCapria, a political writer at the internet’s oldest fact-checking website, Snopes, tells me: “There has always been a sincerely held yet erroneous belief misinformation is more red than blue in America, and that has never been true.”

She points out that when George W Bush was president a multitude of fake stories spread, from claims that he had waved at Stevie Wonder and read a book upside down, to confident declarations that he had the lowest IQ of any president. In the UK, a whole year before “fake news” became a household phrase, there was an unofficial national holiday when it was alleged – with no proof – that the then prime minister, David Cameron, had once stuck a certain part of his anatomy into a dead pig.

Nonetheless, LaCapria notes that since Trump’s election fake news outlets have started capitalising on the left’s “wishful thinking”. “[Stories] were clearly rooted in the hope something would change the outcome of the election,” she says. “A lot of what we deal with is information people don’t really want authenticated.”

And this, really, is the crux of the issue. It is easy to tackle the other side’s fake news and much harder to tackle things that we desperately want to be true. The full list of cognitive biases in action when we see and share false stories is too long to list, so here are just a few: the illusory truth effect – the tendency to believe information that is repeated often; confirmation bias – the tendency to seek out facts that confirm your pre-existing beliefs; the continued influence effect – the tendency to believe false information even after it has been corrected; and most importantly, the bias blind spot – the tendency to see yourself as less biased than other people.

We have been ignorant to dismiss people who believe in fake news as stupid, when we all can and do fall prey to such psychological biases. Yet these age-old cognitive tricks are now exacerbated by modern technology, which allows us to spread false information quickly while ensuring we are trapped in a soft, comforting bubble of people who won’t bother to correct us.

The good news is that you can help stop the spread of left-wing fake news at any time, and the bad news is that you probably don’t want to. Last month a viral post of two pictures side by side claimed that a photo Trump alleged was taken at the “Winter White House” (his Mar-a-Lago estate) was actually taken at an auction house. Thousands shared the post, so that when I saw Snopes’s debunking I felt compelled to pass it on. I wanted people to know it wasn’t true, but after sharing it I felt worried. What if people interpreted it as support for Trump? Social media has become a battleground of polarised politics, and we are so busy fighting each other that I felt like a traitor for exposing the chinks in our own armour.

However, if you can’t stomach calling out other people for spreading fake news, you should at least admit when you yourself make mistakes. Last month, a Time magazine reporter wrongly tweeted that the bust of Martin Luther King, Jr had been removed from the Oval Office, before tweeting twice to concede – and apologise for – his mistake. It is painful to imagine the hot flush of embarrassment that undoubtedly followed him around for days, but we must all follow his example in correcting our mistakes rather than hide behind the Delete button. After all, if there is one man who has trouble admitting he’s wrong, it’s the 45th president of the United States.

In the end, isn’t your own embarrassment a small price to pay to tackle post-truth politics? If your answer is no, then I have another question for you. Did you know the word “gullible” isn’t in the dictionary?

This article appears in the 08 Feb 2017 issue of the New Statesman, The May Doctrine