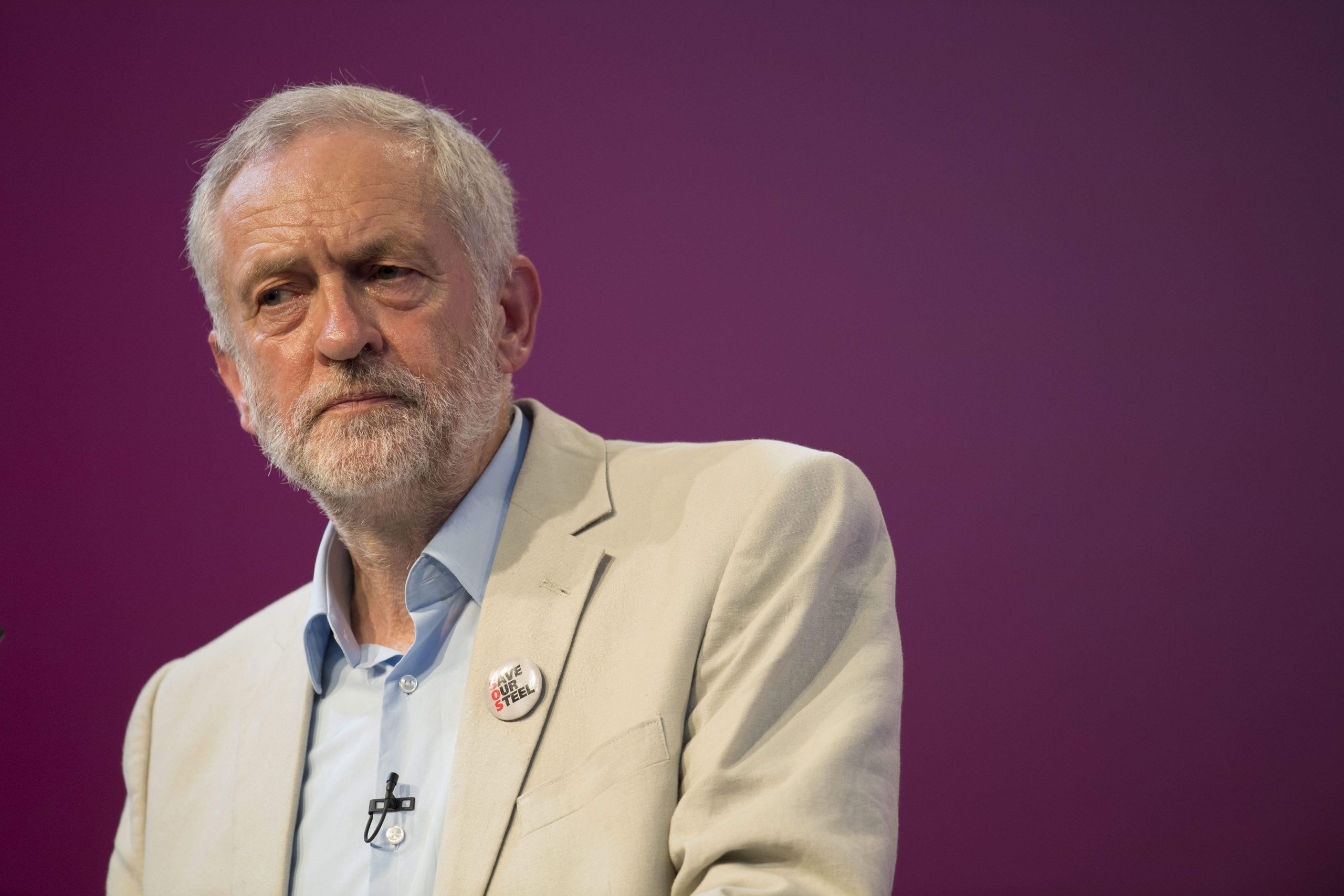

It is perverse, absurd even, that in the aftermath of such a monumental victory Jeremy Corbyn must immediately talk of coalition building and compromise. Previous winners of internal struggles – most notably Tony Blair and Neil Kinnock – certainly did nothing of the sort, and Corbyn’s victory is bigger than theirs. To an extent, this is not the victory of one set of ideas but the establishment of a new party altogether – with a completely different centre of gravity and an almost completely new membership.

That new Labour party – and core project that has built around Corbyn’s leadership – is itself a delicate network of alliances. The veterans of big social movements, from the Iraq War to the anti-austerity protests of 2011, find themselves in bed with left-leaning cosmopolitan modernisers and the reanimated remnants of the old Labour left. All parts of the coalition have reason for hubris, to believe that this new formation – complex enough as it is already, and filled with ideas and energy – can carry the Corbyn project into Number 10 with or without the co-operation of his Labour colleagues and the wider left.

That vision is a mirage. Labour has undergone the biggest membership surge in its history, and is now the biggest left of centre party in Europe. As John Curtis has pointed out, the party’s support has maintained a high floor relative to the level of infighting and sniping over the summer, in part because of Corbyn’s strong appeal to Labour’s base. But the bleak electoral outlook, compounded by boundary changes, requires us to do more than read out lines from pre-written scripts. We must all, from a position of strength, stare death in the face.

The terms of peace with the Labour right must be negotiated carefully. There can be no negotiating away of internal democracy in the selection of candidates or national policy-setting; doing so would permanently weaken the left’s hand and allow Corbyn’s detractors in parliament to run riot. And in policy terms, Corbyn cannot compromise basic anti-austerity principles – not just because doing so would be a betrayal that would demobilise Labour’s new base, but because the project of triangulation pioneered by Ed Milliband is a tried and tested electoral failure.

And yet the need for peace is overwhelming. At a grassroots level, Owen Smith’s support was not made up of hardened Blairites. Many of them, unlike Smith himself, really did share Corbyn’s political vision but had been ground down and convinced that, regardless of the rights and wrongs, there could be no end to Labour’s civil war without new leadership. The left’s job is to prove those people, and the politicians who claim to represent them, wrong.

Labour’s assorted hacks – on left and right – often forget how boring and irrelevant the search for Labour’s soul looks to a wider public that long ago left behind party tribalism. The intellectual task ahead of us is about framing our politics in a comprehensible, modernising way – not creating a whole new generation of people who know Kinnock’s 1985 conference speech by rote.

A united Labour Party, free to focus on shifting the consensus of British politics could well change history. But the grim realities of the situation may force us to go even further. To get a majority at the next election, Labour will need to gain 106 seats – a swing not achieved since 1997.

Add to that the socially conservative affirmation of the Brexit vote, and the left’s profound confusion in terms of what to do about it, and the challenge of getting a Labour Prime Minister – regardless of who they are or what they stand for – looks like an unprecedented challenge. That unprecedented challenge could be met by an unprecedented alliance of political forces outside the Labour party as well as inside it.

In order for Labour to win under the conditions set by the boundary review, everything has to be calibrated right. Firstly, we need an energised, mass party which advocates radical and popular policies. Secondly, we need the party not to tear itself apart every few months. And yes, finally, we may well need an honest, working arrangement between Labour, the Greens, and other progressive parties, including even the Lib Dems.

Exactly how that alliance would be constituted – and how far it would be under the control of local parties – could be the matter of some debate. But there is every chance of it working – especially if the terms of the next general election take place in the context of the outcome of a Brexit negotiation.

The starting point for that journey must be a recognition on the part of Corbyn’s opponents that the new Labour party is not just the overwhelming democratic choice of members, but also – with a mass activist base and a mostly popular programme – the only electable version of the Labour party in the current climate. For the left’s part, we must recognise that the coalition that has built around Corbyn is just the core of a much wider set of alliances – inside Labour and perhaps beyond.