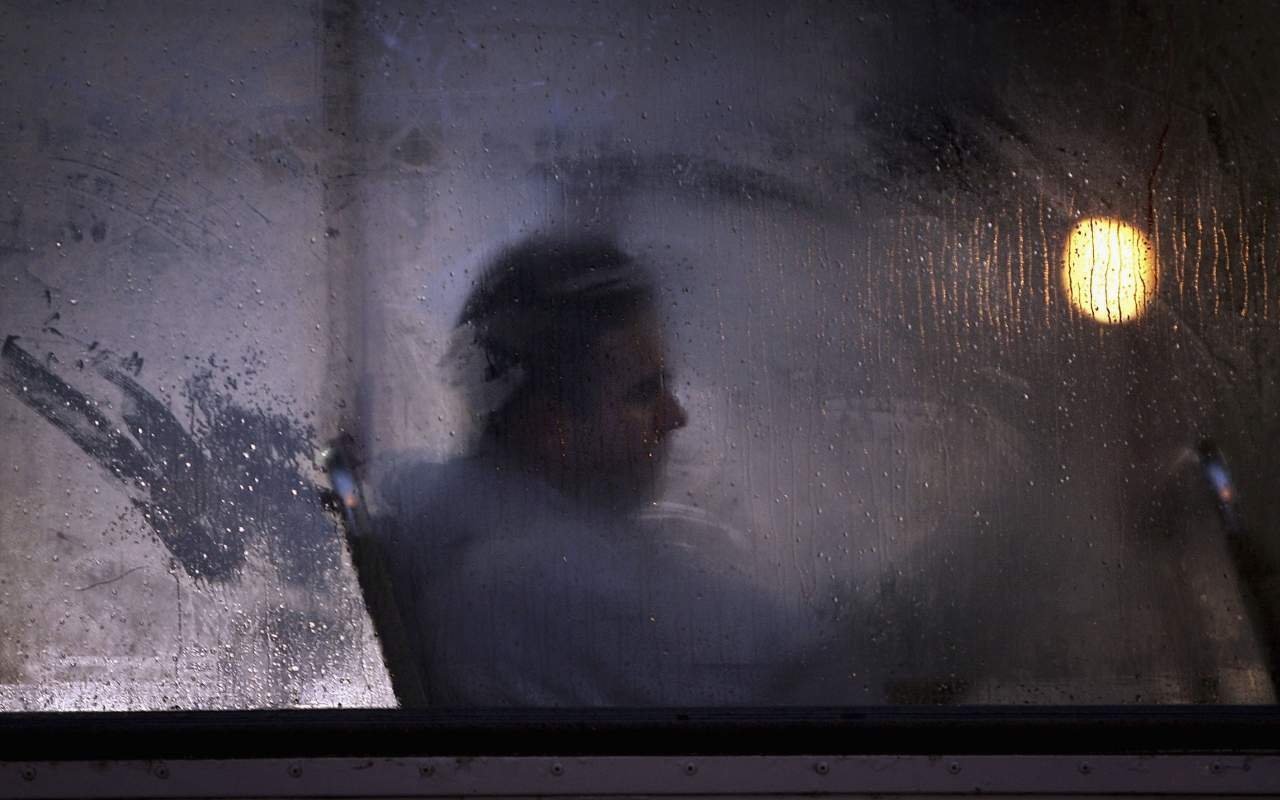

The start of 1995 would have been the worst time in my life, if only I could have mustered up the will to care. Aged 19, severely relapsed into anorexia and depression, I spent most of January and February holed up in a college room, avoiding food, swigging vodka in in the dark while listening to The Smiths. I am nothing if not a dedicated follower of cliché.

My favourite album was Hatful of Hollow, my favourite track, “Still Ill”. I’d rewind the cassette again and again just to listen to that one song.

“Does the body rule the mind or does the mind rule the body?

I dunno.”

Tracing the contours of my bones through paper-thin skin, I considered these lines very deep and meaningful. Meaningful of what, I couldn’t say, but meaningful all the same.

Over twenty years later, I am unfussed over whether my anorexia was a disease of the mind or the body. I consider it both and neither. Certainly, I no longer feel guilt over “choosing” such a destructive path. It was a thousand things at once: an addiction to hunger, flight from puberty, the embrace of a puritan aesthetic in defiance of a world I couldn’t control. Bundle them up together and give it a name: Anorexia. Ana. Call it whatever you want.

In therapy we were encouraged to think of anorexia as a hostile being controlling us, almost akin to demonic possession. Don’t listen to the voice telling you not to eat. Cast it out. I never really bought into this. Mere metaphor would not save me. That said, I’ve no idea what helped me to survive when others didn’t. More often than not, I consider it to have been my inner greedy pig (but then again, that’s just the kind of thing “the voice” would want you to believe).

Both sufferers of mental illness and those who campaign on their behalf face a dual challenge: living with the illness itself while confronting the stigma that surrounds it. There is enormous pressure to take a simple approach when doing the latter. After all, you are dealing with a confused and frightened public; there’s no point in complicating things further. You are then only left with the choice of which way to jump.

Do you take the line that mental illness patients are “just like us”, symptoms all but invisible? Do you go all-out for a social model which presents the world as mad, the patient as sane? Do you encourage people to think of depression, schizophrenia and bipolar disorder as conditions no different to diabetes, heart disease or a broken arm? It all depends, I think, on what you most want to achieve: to convince people that mental illness is not dangerous or to convince them that it is real.

Earlier this month, over the course of World Mental Health Day, I noticed that the urge to draw comparisons between mental and physical health seemed particularly strong. “You wouldn’t say that to someone with cancer /a headache / a broken leg!” was the order of the day. It’s an incredibly effective tactic, drawing attention to the way in which often, we don’t quite believe that someone with depression, psychosis or an eating disorder isn’t putting it on. Mental illness is hard enough to understand and empathise with; making it akin to physical illness helps to take away the fuzzy edges, where sickness overlaps with “normal” behaviour and helplessness overlaps with choice. Nobody chooses to be mentally ill; nobody chooses not to get well. This is something which cannot be stressed enough. Even so I think that, for me, those fuzzy edges existed and exist today.

During the late Eighties I experienced treatments for anorexia based solely on punitive behaviour modification techniques. Sent to an ordinary children’s ward, I found myself compared unfavourably to the patients around me, those who were “properly” ill. Years later, when I finally came into contact with anorexia sufferers who were sicker than me, I was surprised to find that suddenly I was the one who couldn’t believe that they weren’t putting it on. They frustrated me, the desperately ill ones, with their joke shop skeleton faces and wheedling excuses. It took one of them dying to convince me that they were for real. Meanwhile I choose to get better, or I did get better, or some combination of the two. And afterwards I spent years worrying that if I could get better in 1995, why not in 1994 or 1993 or even earlier? Why get ill at all? If it had been a “proper” illness, why hadn’t it needed a “proper” cause, a “proper” cure? Maybe the nurses on the children’s ward had been right.

I was and remain partly in love with the twisted aesthetics of anorexia, an imaginary version of the disorder that used to call to me when I was sitting in the dark, fingernails blue and joints chafing. It holds the attraction of an identity, fragments of a tragic life story, something which I’ve always felt I lacked. I could tell you “but that is not the illness. The illness is something different. The illness is walking round Sainsbury’s every day, following the same route, picking up the same items, reading the nutrition labels, putting them back, wiping your hands on your skirt, maybe buying some items, storing them under your bed for no reason, repeat and repeat until it gets dark.” I could say it is that and only that. But the illness is everything put together. It doesn’t make it less real.

I have grown uneasy with the pressure to validate mental illness by analogy with the physical. In a truly compassionate society this would not be necessary. We risk turning suffering into an identity, a foregone conclusion, a test of whether one really, really deserves to get help. We risk asking those suffering to conform to a fantasy version of their disorder, in which happiness is weakness and recovery a sham. I understand why we do it, but we risk making mentally ill people feel they have something to prove. They don’t.

“Does the body rule the mind or does the mind rule the body?”

I am one of those lucky enough to have learned not to care.