4-10 September 2015

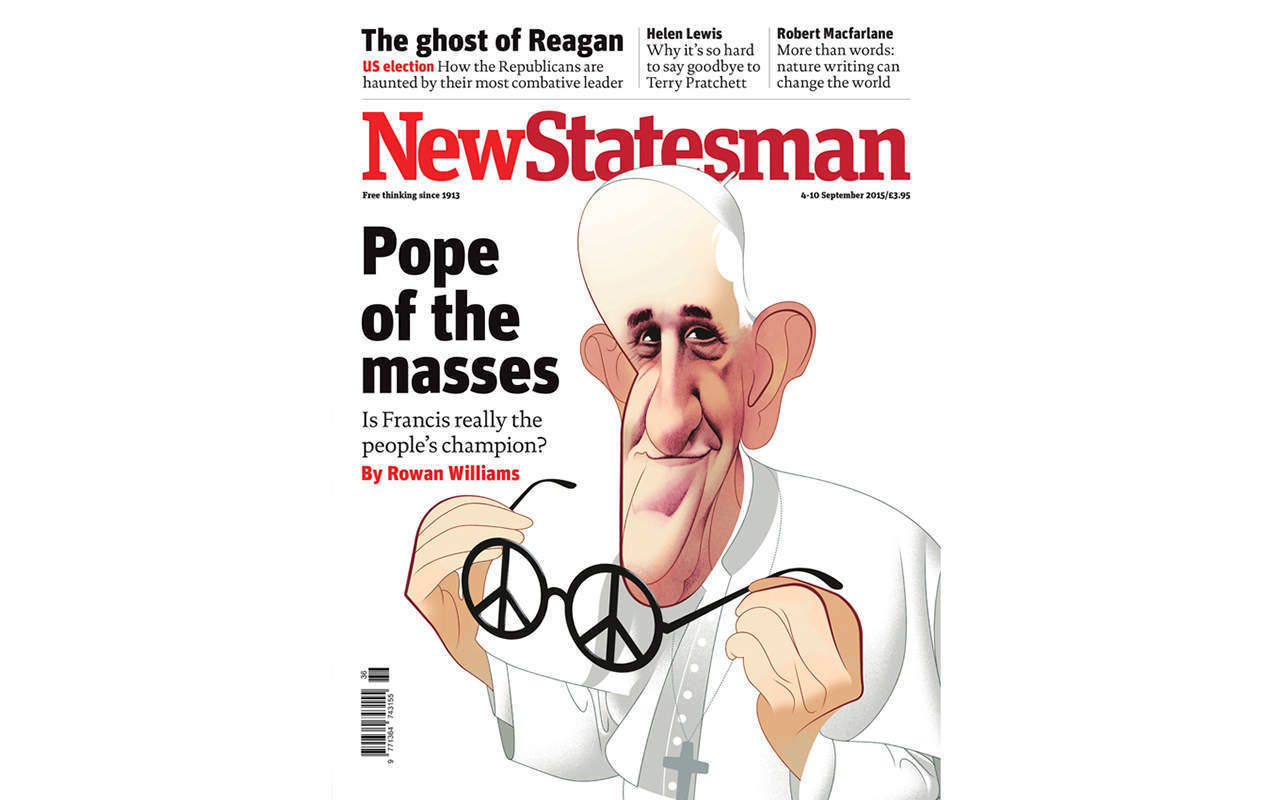

Pope of the Masses

Featuring

Rowan Williams asks – what are the politics of Pope Francis?

The NS Leader: The wretched of the earth.

Anatomy of a crisis: The global statistics on asylum.

Guns, gravy and the Grand Old Party: K Biswas reads charm offensives from seven Republican presidential hopefuls.

Robert Macfarlane: How a new “culture of nature” could change our politics.

George Eaton: After so badly misjudging the Labour leadership contest, how will the Blairites handle Corbyn?

Plus

The new New Statesman website:

In the past five years, the New Statesman‘s website has grown beyond all our expectations. In 2010 barely half a million readers a month were visiting it; now, there are two million, each reading several articles – pretty impressive for a magazine with such a small staff. The way we read online has changed in that time. More than half of those looking at our site now do so on a mobile phone or a tablet, rather than on a computer. Despite fears that the digital age would diminish readers’ attention span and erode quality journalism, the internet has only increased the audience for long-form reporting, informed opinion and good writing, as more people than ever are able to find and share them.

To reflect this, we are launching a new New Statesman website. The design is simple, clean and eminently readable, and fully optimised for screens small and large. We have made the navigation more intuitive and the typography more elegant: it will be easier for you to find the articles, columns and reviews you enjoy in the magazine, as well as our web-only offering of fast-paced Westminster coverage, cultural comment and opinionated blogging.

Rowan Williams: What are the politics of the Pope?

Pope Francis appears liberal in some senses, but deeply conservative in others. The former archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams discusses the politics of this “equal opportunities annoyer”:

Reports in recent months suggest that approval ratings for Pope Francis have declined sharply in the United States since the publication of his encyclical on the environment, which framed climate change as “one of the principal challenges facing humanity today” and argued that wealthy nations had a moral responsibility to tackle it and to pay their “grave social debt” to the poor. It seems very unlikely that he is losing any sleep over this; and no doubt his visit to the US later this month will revive the figures. But it is a phenomenon worth thinking about. For non-Roman Catholics, there is a certain wry satisfaction in watching conservative Catholics, mostly in North America – commentators who gladly treated every pronouncement by Francis’s two immediate predecessors as maximally authoritative – wriggling through explanations that of course the Pope’s views on climate change or capitalism are just his personal opinions, and as such of purely academic interest to the faithful. In the wonderful phrase quoted by Paul Vallely in the new edition of his book Pope Francis: Untying the Knots, Francis is an “equal opportunities annoyer”: he is not moving fast enough for liberals on the women/gays/divorce/abortion cluster of issues, and he is not saying enough about these things to keep conservatives happy, wasting his energies and compromising his authority by sounding off about poverty and environmental crisis.

Williams argues that attempts to categorise the Pope as right or left can only fail:

Conservative or liberal? The Pope’s record might prompt us to ask whether these categories are as obvious or as useful as we assume. As various commentators have astutely noticed, the Pope is a Catholic. That is, he thinks and argues from a foundational set of principles that are not dictated by the shape of political conflict in other areas. It is difficult for some to recognise that his reasons for taking the moral positions he does on abortion or euthanasia are intimately connected with the reasons for his stance on capitalism or climate change.

The Catholic conservative who has unthinkingly rolled up the pro-life agenda with support for the death penalty, the National Rifle Association, US foreign policy and the uncontrolled global market finds this as shocking as the Catholic (or, indeed, non-Catholic) liberal who thinks in terms of a single “progressive” or emancipatory agenda that the Pope is failing to support consistently. But “conservative” and “progressive” imply that we all know there is one road for everyone on which we may move forward or backwards, rapidly or slowly. It doesn’t hurt to be reminded from time to time that this assumption can be an alibi for lazy thinking. The Catholic tradition of ethics and theology sets out a model of what is abidingly good and life-giving for human beings which does not depend on this model of a single road towards a given future. It is about making choices that bring you closer or otherwise to a particular vision of human well-being; and those choices do not necessarily map directly on to other, familiar taxonomies.

[. . .]

In other words, it is futile to expect this pope or any other simply to fit the ready-made stereotypes. Pope Benedict “looked” conservative; Pope Francis “looks” liberal. Yet that tells you nothing at all of interest about them. And it obscures a simple fact: Benedict’s theology, though cast in a different and less accessible idiom, is entirely of a piece with all that Francis has said in his major public essays about evangelism and now about ecology. Even the contrast in style between them can be exaggerated a little. Paul Vallely notes that Francis has chosen to sit on the same level as his guests on formal occasions. Benedict did the same at the interfaith event in Assisi some years ago; he was also the first to break the taboo on the Pope eating in public with others.

Read the article in full below.

Leader: The wretched of the earth

The NS Leader this week turns to the question of asylum and condemns the British government for its lack of action.

The quality of our public discourse on asylum is lamentable. The Conservative government, preoccupied with its absurd immigration caps and targets (all missed), has shown little leadership on the issue. In an excellent speech on 1 September, Yvette Cooper correctly denounced the “political cowardice” of ministers for failing to respond adequately and compassionately to the plight of asylum-seekers fleeing turmoil in North Africa and the Middle East. She contrasted the government’s inaction with Britain’s proud traditions of welcoming incomers and the most desperate refugees.

[. . .]

In 2014, the UK granted asylum to just 14,000 people, compared to the 47,500 taken by Germany. This year, as many as 800,000 are expected to apply to Germany. Chancellor Angela Merkel has said that the refugee crisis “will concern us far more than Greece and the stability of the euro”, and German regional leaders have agitated for greater federal funding and faster processing of asylum claims. Such an approach is absent from much of the rest of the continent: many European nations seem to have resolved that the best way to deter asylum-seekers is to treat them deplorably. The Dutch government has announced plans to cut off the supply of food and shelter for those who fail to qualify as refugees.

Nor has the EU distinguished itself. A proposal made in May for member states to admit 40,000 asylum-seekers between them has collapsed. The EU has also failed to engage other nations in a larger multilateral response to alleviating the crisis: the wealthy Gulf states, which keep their borders firmly closed to the desperate of Syria, ought to be shamed into action. As many as 2,500 people have died attempting to cross the Mediterranean this year; across the EU, the number of applications for asylum reached the record figure of 626,000 in 2014 and it will be even higher in 2015.

David Cameron can legitimately say that he is operating in a climate of great hostility to migrants and asylum-seekers – just read the tabloid headlines. Yet leadership is about informing public opinion, not merely following it. The Prime Minister has a rare opportunity to shape a more enlightened and compassionate public discourse.

Read the Leader in full below.

Anatomy of a crisis: The statistics on asylum

An NS data spread this week explores the refugee crisis in detail.

Guns, gravy and the Grand Old Party

K Biswas explores the manifestos and memoirs of seven Republicans vying to run as the GOP’s presidential candidate, and finds the 2016 race haunted by the ghost of Ronald Reagan.

On Donald Trump:

[. . .] Trump (who told Playboy in 1990 that he would only ever run “if I saw this country continue to go down the tubes”) benefits from decades-long associations with TV shows, glamorous wives and skyscrapers. Although Trump, as poll leader, is lavished with the press attention he craves, bids by the more eccentric candidates have been derailed in the past. Four other men led the Republican race in 2012 before Mitt Romney won the nomination; they included Newt Gingrich, who promised to fire lasers at North Korea and colonise the moon by 2020, and the pizza magnate Herman Cain (“The more toppings a man has on his pizza, I believe the more manly he is”).

On Ted Cruz:

A free-market social conservative well liked by the Republican Party faithful, Cruz works in his Senate office beneath a giant oil painting of Reagan at the Bradenburg Gate in Berlin which Cruz commissioned after his election to the upper house. A Time for Truth deftly claims his hero’s inheritance, offering parallels with the great leader’s modest backstory. Each man had a strained relationship with his father (Cruz’s dad walked out on him at three years old and did not return until months later; Reagan’s was an alcoholic), close bonds with a put-upon mother (Cruz: “my mother has been a best friend for as long as I can remember”), religious revelations, and strange hobbies involving animals (Reagan kept birds’ eggs, Cruz caught bullfrogs).

On Rand Paul:

Rand Paul’s Taking a Stand further asserts that, rather than rally against the power of the executive – a goal that the GOP has pursued loudly throughout the Obama years – voters should be far more suspicious of congressional democracy. His pitch for the role of “anti-politics” candidate argues that “No one will tell the truth” in a “screwed-up Washington” where “logic is the exception”. Members of Congress, Democrat and Republican, are overcome by “tribal righteousness, petulance, apathy and plain old laziness”, and spend their time “blowing hot air at one another across the aisle”.

On Rick Santorum:

[. . .] Santorum emerges as a politician who undertakes God’s work as a career. Bumped from the first prime-time [Republican candidates’] debate because of his poor polling, this second-time entrant and devout traditionalist borrows heavily from the word of the Almighty. Each chapter of Bella’s Gift, the saccharine family memoir he has co-written with his wife, begins with a quotation from the Bible. He announces: “I came to the Senate and found the Lord!” We gain an insight into his priorities as we see Karen Santorum “put her professional dreams on hold to put family first and help me pursue my calling” and his children home-schooled, “to be in rhythm with my Senate schedule”. He proudly walks us through the introduction of his bill curtailing abortion rights (“I felt certain I was following God’s will . . . and my prayer life was better than ever”) and then uses his experience as the father of a disabled child to advance his “pro-life” position, slam the Affordable Care Act (“Obamacare”) and offer relationship advice: “We see Jesus as the model for us in marriage as in everything.”

On Ben Carson:

Carson, the only African American in the GOP race, believes that his upbringing and “horrible life” in “dire poverty” in Detroit, Michigan, profoundly affected his political journey. He was “plagued by a violent temper”, at one point almost killing a classmate with a knife. His juvenile inkling that “someone was always infringing on my rights” continued into adult life, the author taking a scattergun approach as to what comprises his nation’s bloated fifth column – “pop culture, Hollywood, politicians and the media”, government in its “quest for total control of our lives”, secular progressives who have “beaten [the public] into submission”, and the “PC police” who “muzzle the populace”, so that people are afraid to say “Merry Christmas” at Christmas-time.

On Mike Huckabee:

Huckabee clings to the Culture Wars for dear life, believing that young people have been corrupted by sex tapes, twerking and reality TV; feminism has gone too far because sitcoms and commercials portray men as “buffoons”; and the “angry, profanity-laced rants” of gay activists are tolerated only because the president is “cheerleader-in-chief for all things gay”. Sounding at times like a column by a concussed Richard Littlejohn, God, Guns, Grits and Gravy is replete with punchy exclamations (“Well, la-de-freakin-da!”) and infantile similes (talking to New Yorkers about guns is like “announcing in a synagogue that one owns a bacon factory”).

Robert Macfarlane: How a new “culture of nature” could change our politics

Mark Cocker’s interrogation of “the new nature writing”, which the NS published in June, provoked a heated debate. In this reply, Robert Macfarlane argues that a new “culture of nature” is changing the way we live – and could change our politics, too:

A 21st-century culture of nature has sprung up, born of anxiety and anger but passionate and progressive in its temperament, involving millions of people and spilling across forms, media and behaviours.

This culture is not new in its concerns but it is distinctive in its contemporary intensity. Its politics is not easily placed on the conventional spectrum, so we would do better to speak of its values. Those values include placing community over commodity, modesty over mastery, connection over consumption, the deep over the shallow, and a version of what the American environmentalist Aldo Leopold called “the land ethic”: the double acknowledgement that, first, human beings are animals and, second, we are animals among other animals, sharing our habitat with members of the biota that also have meetable needs and rights.

Macfarlane writes that the new swell of literature addressing this topic has the power to change our society:

Literature has the ability to change us for good, in both senses of the phrase. Powerful writing can revise our ethical relations with the natural world, shaping our place consciousness and our place conscience. Roger Deakin’s Waterlog (1999) prompted the revival of lido culture in Britain and the founding of the “wild swimming” movement. Richard Mabey’s Nature Cure (2005) is recommended by mental health professionals. Chris Packham fell in love with wild cats and golden eagles because he read Lea MacNally’s Highland Deer Forest (1970), as a child growing up in suburban Southampton.

“Nature writing” has become a cant phrase, branded and bandied out of any useful existence, and I would be glad to see its deletion from the current discourse. Yet it is clear that in Britain we are living through a golden age of literature that explores relations between selfhood, landscape and ethics and addresses what Mabey has described as the “growing fault line in the way we perceive and talk about nature”. I don’t know what to call this writing, nor am I persuaded that it needs a name. It is not a genre or a school. An ecology, perhaps? In the Guardian in 2003, I described what I saw as the green shoots of a revival of such writing. Twelve years on, those shoots have flourished into a forest, richly diverse in its understory as well as its canopy.

As such, Macfarlane condemns Cocker’s attack on the genre:

Not everything in the forest is lovely and not all of this writing is to the taste of every reader. More voices need to be heard from ethnic-minority writers and from a wider range of identities and backgrounds. There could also be a lot more jokes. But there is no one true way of writing about nature and place. The tradition of such literature has always been, as I argued in 2003, “passionate, pluriform and essential”. Our contemporary version mixes ire, irony and the irenic; green ecologies with dark ecologies.

It is the hopefulness, commitment and diversity of the current field that made Mark Cocker’s recent attack on it seem so disappointingly crabbed. In June, Cocker wrote an article for this magazine suggesting that the so-called new nature writers – including me and Helen Macdonald – were politically passive and insufficiently invested in the natural world. The standfirst asked: “How much do [these] authors truly care about our wild places?” Cocker went on to caricature much of the recent work as “pastoral narratives” that fail to engage with the “troubling realities” of modern Britain.

Nature books, he wrote, must navigate “between joy and anxiety” (as if they didn’t already, obsessively) and must have “real soil” at their roots. Does Macdonald’s H Is for Hawk – which never self-identifies as nature writing anyway – not have real soil at its roots in the form of her father’s sudden death and her grief? Implicit throughout Cocker’s article were the ideas that only those with “naturalist” knowledge should be writing about nature and that nature is a category confined to the non-human, as separable from “landscape” as “culture” is separable from “literature”.

It was a regrettable piece of policing. Its manners were especially unfortunate, because at its heart Cocker – a fine writer and ornithologist – was asking valuable questions about how cultural activity connects to political change. He was right to sound the alarm for the living world but his suggestion that any literary engagement with nature must be noisily game-changing was wrong. Such an instrumentalising view subdues literature to a single end and presupposes a simplistic model of consequence: that Cultural Action A leads to Political Outcome B.

He concludes:

We must bring about the “major reawakening by our political classes to the idea that civilisation is rooted in a genuine and benign transaction with non-human life”, as Cocker puts it. But this won’t be magically managed by a single silver bullet – rather by what the climate scientist Richard Somerville brilliantly calls “silver buckshot, the large number of worthwhile efforts that all need to take place”. So down with disdain and division, up with celebration and connection – and onwards in a hundred hopeful steps towards an ecology of mind.

George Eaton: After so badly misjudging the leadership contest, how will the Blairites handle Corbyn?

In the Politics Column, George Eaton writes that when Labour lost the general election in May, the party’s “modernisers” sensed an opportunity. But this opening has now been lost to the hard left:

While conducting their post-mortem, the Blairites are grappling with the question of how to handle Corbyn. For some, the answer is simple. “There shouldn’t be an accommodation with Corbyn,” John McTernan, Blair’s former director of political operations, told me. “Corbyn is a disaster and he should be allowed to be his own disaster.” But most now adopt a more conciliatory tone. John Woodcock, the chair of Progress, told me: “If he wins, he will be the democratically elected leader and I don’t think there will be any serious attempt to actually depose him or to make it impossible for him to lead.”

Umunna, who earlier rebuked his party for “behaving like a petulant child”, has emphasised that MPs “must accept the result of our contest when it comes and support our new leader in developing an agenda that can return Labour to office”. The shadow business secretary even suggests that he would be prepared to discuss serving in Corbyn’s shadow cabinet if he changed his stances on issues such as nuclear disarmament, Nato, the EU and taxation. Were Umunna, a former leadership contender, to adopt a policy of aggression, he would risk being blamed should Corbyn fail.

Suggestions that the new parliamentary group Labour for the Common Good represents “the resistance” are therefore derided by those close to it. The organisation, which was launched by Umunna and Hunt before Corbyn’s surge, is aimed instead at ensuring the intellectual renewal that modernisers acknowledge has been absent since 2007. It will also try to unite the party’s disparate mainstream factions: the Blairites, the Brownites, the soft left, the old right and Blue Labour. The ascent of Corbyn, who has the declared support of just 15 MPs (6.5 per cent of the party), has persuaded many that they cannot afford the narcissism of small differences.

Eaton concludes:

The challenge for the Blairites is to reboot themselves in time to appear to be an attractive alternative if and when Corbyn falters. Some draw hope from the performance of Tessa Jowell, who they still believe will win the London mayoral selection. “I’ve spoken to people who are voting enthusiastically both for Jeremy and for Tessa,” Wes Streeting, the newly elected MP for Ilford North, said. “They have both run very optimistic, hopeful, positive campaigns.”

But if Corbyn falls, it does not follow that the modernisers will rise. “The question is: how do we stop it happening again if he does go?” a senior frontbencher said. “He’s got no interest or incentive to change the voting method. We could lose nurse and end up with something worse.” If the road back to power is long for Labour, it is longest of all for the Blairites.

Read the column in full below.

Plus

Laurie Penny: No sick person responds to their diagnosis by thinking, “I can scam taxpayers for £73 a week!”

Barbara Speed on Hillary Clinton’s emails and the way we do politics.

Helen Lewis: Goodbye to Terry Pratchett, the only writer who ever truly conquered my inner cynic.

Sophie McBain on Hans Asperger, autism and Steve Silberman’s Neurotribes.

Caroline Crampton: Why radio comedy has flourished in the digital age.