Energy prices have been back in the news recently as Ed Miliband’s fabled freeze started to thaw under the heat of changing oil prices and condemnation from various business leaders. Of course so much fuss has been made of the rhetorical conversion from “freeze” to “cap” because the policy had previously been one of Labour’s major wins this parliament. Their opponents are now smiling as it appears to have fallen apart.

Economics and the merit of the idea aside however, the announcement surrounding the energy price freeze does still represent an interesting case study of Labour effectively combining campaign communications and research.

When Miliband first announced the idea on that sunny September afternoon in Brighton in 2013, he took just about everyone by surprise. It had not leaked nor been briefed and came as a genuine shock not just to the public, but also to those in the media and the know. Labour had clearly done their research, with an insider memorably reported as enthusing that their focus groups had shown support for the idea “off the charts”. ComRes had also may have played a part, having polled on energy prices for BBC Radio 5Live’s Energy Day earlier in the month – and found a fairly ugly mood among consumers. Resentment towards energy companies about labyrinthine tariffs, seemingly endless price increases and poor customer service had been well known for years but seldom activated politically, at least in this Parliament.

This changed with Miliband’s pledge. The Labour news grid appeared, on this occasion, to light up, with Miliband and Caroline Flint touring the news rooms, followed by an article a few days later by Douglas Alexander claiming the idea to be the intellectual descendant of New Labour’s popular windfall tax on energy companies in 1997.

Despite focus groups not tending to produce charts, public polling soon proved the Labour strategist’s point as levels of support for the plan were shown reaching astonishing levels of up to 80 per cent, which in turn took the story into another news cycle. Here at ComRes we first knew of the pledge’s success not when we saw the numbers, but when various clients asked to move the focus of their regular polling away from the upcoming Conservative Conference as had been planned, and towards testing attitudes towards the energy price freeze instead. Newspaper columns were filled with debates about the policy throughout the rest of the autumn. Radio talk shows spent weeks discussing it.

Curiously though, as some mentioned at the time, was that the next general election looked as if it might swing on the seemingly negligible issue of an £80 annual change to energy bills. It paled in comparison to other issues of the day such as the war in Syria, youth unemployment or a public debt running above £1tn. The key to the appeal of the energy price freeze though, was not how much it affected people, but how many people felt it would affect them – even if only negligibly.

Having proposals with a wide appeal may appear obvious, but stands in complete contrast to the strategy the party then took ahead of its disappointing European election campaign last year. Here Labour had a series of announcements lined up, all connected by their cost of living theme: extending free childcare, capping rent increases and creating a state-owned corporation to compete against private companies for rail franchises in an attempt to bring down commuting costs.

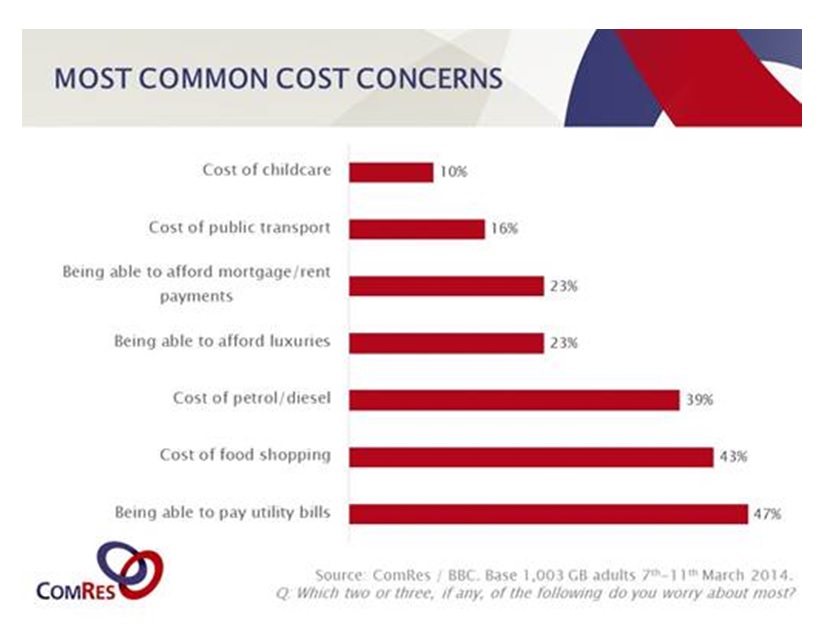

Also linking these issues was that they were meant to be low incidence but high salience proposals: only a small proportion of the population would be affected, but those people would benefit in a big way. As can be seen from ComRes polling at the time, although relatively few people were concerned about the cost of housing (23 per cent), public transport (16 per cent) and childcare (10 per cent), they were all issues which clearly had obvious segments of the population interested in them (renters, commuters, parents of young children).

(Click on graph to enlarge).

The thinking behind this appeared to be a desire to emulate Barack Obama’s successful Presidential re-election campaign in 2012, where voters were apparently delivered hyper-targeted messages focusing on the issues they cared about most. It was also perhaps indirectly influenced by the current corporate Steve Jobs-inspired vogue for niche products, following Apple’s ascent through a relentless focus on quality, good design and for many years, catering to a fairly small but incredibly loyal segment of the market (The Economist and Moleskin being other commonly cited examples of this).

Unlike Labour though, Obama’s campaign had a billion dollars and the most sophisticated digital campaign infrastructure ever and thus was supposedly able to deliver these localised messages. One might also question how influential this approach actually was or whether the election result simply reflected President Obama’s superiority over a gaffe-prone, fairly middle-of-the-road opponent.

In any case, with Labour’s digital strategy focused on mobilising volunteers rather than winning the hearts of the general public, it relies on other media to deliver its message to voters.

This made it very difficult to construct an effective communications campaign around its “low incidence” pledges at the European elections. The ideas likely went down well in focus groups among key demographics but gained little traction when released during the campaign.

Whereas large numbers of people felt resonance with the energy price freeze, relatively few felt the same about rent increase caps or expanded childcare. This meant that beyond the original announcements, Labour received little media attention for their proposals. As they were of interest to only few of the press’s readers and the broadcasters’ viewers, there was little incentive for them to produce more content on the issues. The lack of traction for the proposals, together with Ed Miliband’s mixed popularity with his own side, also meant few MPs were willing to keep repeating the lines about them and that message discipline broke down. All of which undoubtedly contributed to an underwhelming second place European election finish with 26 per cent of the vote. Even now, there is precious little chance of stopping a random person on the street and their knowing about any of Labour’s pledges on railways or rents.

So what are the lessons? First, don’t forget the medium: however attractive a policy is, it will only be popular if people know about it, which means that you need a way of telling them. This requires having something to offer the people you want to carry your message.

Second, follow a strategy that marries research and communications expertise, with clear messaging based on robust evidence. There are plenty of communications professionals who try passing a finger in the air as insight, but data on a page also has its limitations. Research should be translated into actionable findings and clear guiding principles which can then be combined with political knowledge to form a comprehensive and coherent strategy.

Which just leaves us with the general election. This all suggests it will not be won and lost on niche issues, but on general perceptions and feelings about one or two major issues which affect everyone. There are likely to be related to the NHS, personal leadership qualities and one of the main variants of economic trust (growth, proceeds of growth, cost of living). And, as Ed Miliband knows from his experience of the energy price cap issue, the winner will need more than a little luck.

Adam Ludlow is a consultant at ComRes