After weeks of increasingly fractious debate, MPs will vote today on the government’s Welfare Benefits Uprating Bill, which enshrines in law George Osborne’s plan to raise benefits by 1 per cent per year for the next three years, rather than in line with price increases. With the support of almost all Conservative and Liberal Democrat MPs, the bill will easily pass the House of Commons (Labour, to its credit, will vote against it) but here are four reasons why it deserves to be defeated.

1. It will force even more of the poorest families to choose between heating and eating

By raising benefits by 1 per cent, rather than in line with inflation, which stood at 2.2 per cent in September 2012 (the month traditionally used to calculate benefit increases), the coalition will leave the poorest families even more vulnerable to fluctuations in food and energy prices. Inflation is forecast by the Office for Budget Responsibility to be 2.6 per cent in September 2013 and 2.2 per cent in September 2014, meaning that those families affected will have suffered a cumulative loss of four per cent of income by the end of the period. For many, this will mean being forced to choose between heating their home and feeding their family.

As the Institute for Fiscal Studies reported yesterday, 2.5 million households without someone in work will lose an average of £215 per year in 2015-16, while seven million households with someone in work will lose an average of £165 per year. If, as in recent years, inflation rises faster than expected, these losses will be even greater.

2. It will damage the economy by reducing real incomes

When wages are stagnant and unemployment is high, benefit payments automatically increase in order to limit the fall in consumer demand. While government borrowing rises as a result, these “automatic stabilisers” have long been recognised as an essential tool of economic policy. In October 2012, George Osborne remarked: “We have never argued that you stop what economists call the automatic stabilisers operating – the lower tax receipts and extra government payments [such as higher benefits] that follow if, for example, the global economy turns down.” Since those on low incomes are forced to spend, rather than save, what little they receive, they automatically stimulate growth.

But Osborne’s decision to cap benefit increases at 1 per cent will reduce the effectiveness of the automatic stabilisers as payments will now fall, rather than rise, in line with inflation, reducing real-terms incomes. As a result, Britain’s anaemic economy will be even more prone to recession.

3. Low wages aren’t a reason to cut benefits

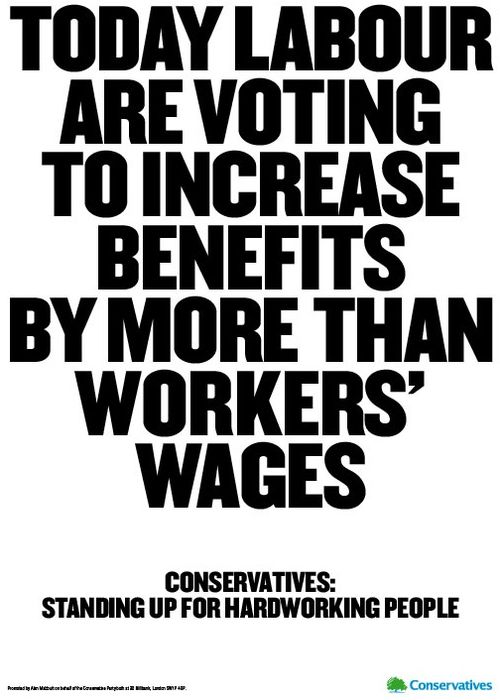

In seeking to justify the bill, the Conservatives have repeatedly highlighted the fact that in recent years benefits have risen faster than private sector wages (see their latest poster). Since 2007, the former have increased by an average of 20 per cent (in line with inflation), while the latter have increased by 11.4 per cent.

But this is an argument for increasing wages (for instance, by ensuring greater payment of the living wage), not for cutting benefits. Many of those whose wages have failed to keep pace with inflation rely on in-work benefits such as tax credits to protect their living standards. The government’s decision to cut these benefits in real-terms (60 per cent of the real-terms cut falls on working families) will further squeeze their disposable income.

When Iain Duncan Smith says that benefits have risen faster than wages, he is really complaining that wages have risen more slowly than inflation (and are expected to continue to do so until at least 2014). But rather than prompting the government to slash benefits, this grim statistic should encourage it to pursue a genuine growth strategy that ensures more people have access to adequately paid employment.

Finally, while benefits have increased faster than wages in the last five years, this is a temporary quirk caused by the recession. Until now, their value relative to wages has plummeted. In 1979, unemployment benefit was worth 22 per cent of average weekly earnings. Today, it is worth just 15 per cent.

4. There are fairer ways to reduce the deficit

The coalition isn’t wrong when it says the deficit, which stood at £121.6bn last year, needs to be reduced (although at a pace commensurate with the state of the economy). But there are fairer ways to raise revenue than cutting benefits for the poorest workers and jobseekers. While reducing welfare payments, the government is simultaneously cutting the top rate of income tax on earnings over £150,000 from 50p to 45p, a measure that will benefit the average income-millionaire by £107,500 a year. Were the government to reverse this measure, it could expect to raise around £3bn a year, more than enough to fund inflation-linked rises in benefits.

Even in the first year of the 50p rate, when temporary forestalling meant many avoided it (for instance, by bringing forward income to 2009-10, the year before the new rate took effect – a trick they could only have played once), the tax raised an extra £1.1bn. This alone is enough to meet the annual cost of increasing benefits in line with inflation (the government expects to save £0.9bn in 2014-15 by capping increases at 1 per cent). But rather than balancing the budget on the backs of the richest (just 1.5 per cent earn more than £150,000), the government has chosen to do so on the backs of the poorest.