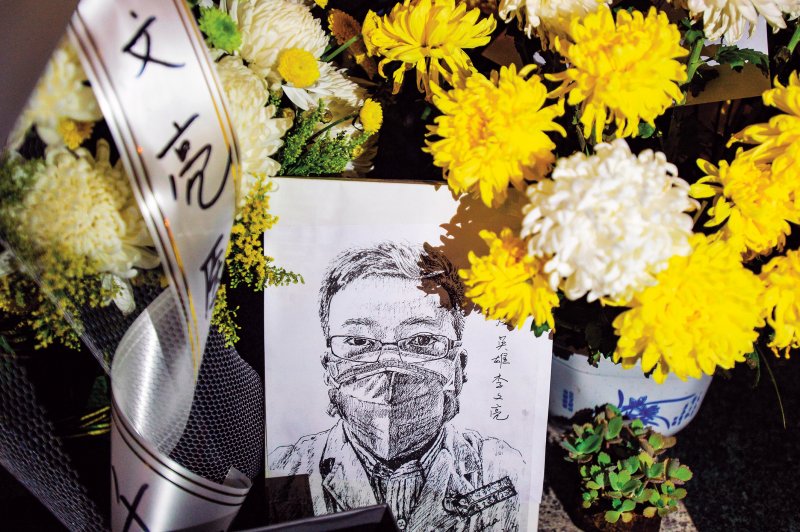

On 6 February, when talk of a global coronavirus pandemic still felt abstract, Li Wenliang, a 34-year-old ophthalmologist, died of Covid-19 in Wuhan Central Hospital, China. Just weeks before his death he was reprimanded by the police for warning his colleagues about a dangerous new strain of pneumonia that appeared to be spreading through the city.

Li’s death marked an emotional flashpoint in China, provoking outrage at the government. Five months later, the global death toll has passed half a million, and the doctor’s heroism continues to move people. The BBC reported in June that Chinese social media users were still posting online messages to Li, but calls for insurrection had been replaced with mundane updates on the weather, personal news and well-wishes – a one-way public conversation that fostered a sense of “communal solidarity” independent of the official government narrative.

Crises can turn ordinary people into heroes; men and women whose lives might have been considered unremarkable had they not, when confronted by a terrorist attack, freak accident or a government cover-up, displayed exemplary moral courage and self-sacrifice. In a better world, Li would be checking people’s eyesight and looking after his two children, the youngest of whom was born in June; he’d be loved by his friends and family and unknown to almost everyone else. In the US and UK, where incompetent and negligent governments have contributed to high Covid-19 death tolls, the pandemic has created millions of heroes and a shared impulse to celebrate them.

In Britain, for ten weeks the nation gathered every Thursday to “clap for carers”. Meanwhile, as the virus rampaged through New York, the city erupted in cheering and applause every evening at 7pm, a ritual that began as a way of expressing gratitude for heroic doctors and other essential workers, and continued because the sense of unity felt good.

In an article for the US magazine the Atlantic, Karleigh Frisbie Brogan, a shop worker, pushed back against the “hero talk”: “It’s a pernicious label perpetuated by those who wish to gain something – money, goods, a clean conscience – from my jeopardisation,” she wrote. Supermarket cashiers are not heroes, “they’re victims. To call them heroes is to justify their exploitation.” Many of the workers being upheld as “heroic” are underpaid and undervalued; they are nurses, cleaners, bus drivers, care workers, delivery drivers and farm labourers sent to work without proper protection. Unlike the kinds of heroes who put themselves in danger to save strangers, or human rights activists resisting murderous dictatorships, essential workers, for the most part, did not choose heroism: they could either bear the risk of catching Covid-19 at work or they could stop working.

Even so, the problem may not be with the accuracy of the hero label as much as with our response to this self-sacrifice: are we allowing self-serving gratitude to detract from efforts to address the government failures and long-standing social injustices that put so many workers at risk? In a searing essay for GQ, the writer Talia Lavin argued that what we demanded of essential workers was not heroism but “insensible, unnecessary martyrdom”. Lavin gave the example of Leilani Jordan, a 27-year-old supermarket worker in Maryland, US, who was not provided with gloves or a mask by her employer. Jordan died of Covid-19 before she could cash her final pay cheque of $20.64.

It’s possible, too, that when we label essential workers as heroes, we place more pressure on people who are already struggling to cope. Elaine Kinsella, a psychologist at the University of Limerick, is conducting a study on the emotional well-being of “Covid-19 heroes” – essential workers in Ireland and the UK – and expressed concern that labelling essential workers as heroic may sometimes place “unrealistic expectations” on them. Kinsella’s previous research has tried to map the social and psychological functions of heroism, and the way the people we celebrate as heroes serve to articulate moral norms and boost community morale in times of hardship.

****

Behavioural scientists have only recently begun studying heroic behaviour. Psychology has traditionally concerned itself with investigating illness or dysfunction, but from the late Nineties a branch known as positive psychology has sought to apply science to our understanding of the good life. One of the central figures behind the small but expanding field of “heroism science” is Philip Zimbardo, the 87-year-old psychologist and emeritus professor at Stanford University who is best known for designing the Stanford Prison Experiment.

In 1971, with the horrors of the Second World War still haunting minds, psychologists were working to understand why humans commit atrocities against each other. Zimbardo created a mock prison inside Stanford University and randomly divided 24 paid student participants into two groups: prisoners and guards. The uniformed guards grew abusive; the prisoners became submissive and began suffering emotional breakdowns. The behaviour grew so extreme that the experiment was called off after six days.

For Zimbardo the project demonstrated the extent to which our environment and social context influence our behaviour. At the end of his 2007 book, The Lucifer Effect, which explored “why good people turn evil”, he argues that the upside to humans’ malleability and susceptibility to influence is that with the right encouragement, we are all capable of incredible goodness. We can all be heroes.

In 2010 Zimbardo founded the Heroic Imagination Project to promote research into heroes and deliver training in schools and organisations on subjects such as how to overcome the bystander effect (the theory that we are less likely to intervene when others are present). The Heroic Imagination Project has helped seed a small cadre of heroism researchers. In 2016, Scott Allison of the University of Richmond, Virginia, and Olivia Efthimiou of Murdoch University in Australia founded Heroism Sciences, a peer-reviewed journal. In May, researchers from around the world were due to meet in Limerick, Ireland, for the third biannual Heroism Sciences conference, which was postponed because of the pandemic.

Unlikely hero: a memorial to the late ophthalmologist Li Wenliang at Wuhan Central Hospital. Credit: Getty

While some researchers are focused on minor, everyday heroism and on how to promote heroic values such as moral courage and altruism, others are keen to study exceptional acts and the rare individuals who will take a risky, altruistic moral stance even when most of their peers remain passive. Li Wenliang might fall into this category, as do the many whistle-blowers – among them scientists and military officials – calling attention to the Trump administration’s appalling response to the pandemic. So too do the have-a-go heroes that frequently star for a few days in newspaper headlines before returning to obscurity – such as Patrick Hutchinson, who in June was photographed carrying away an injured counter-Black Lives Matter protester from a hostile crowd in London, or Lukasz, a kitchen porter working at Fishmonger’s Hall, who was stabbed five times while trying to stop the London Bridge terrorist attacker in November 2019.

I count in this group several friends I made in Libya in the late Noughties who in 2011 astonished me when they braved live ammunition while peacefully protesting against Muammar Gaddafi, the murderous dictator who had governed their country since before they were born. Should I have been able to predict which of them would, given the opportunity, sacrifice their life for a noble but abstract cause?

****

One researcher trying to answer these questions is Ari Kohen, a professor of political science at the University of Nebraska, who was inspired to study heroism in part because of his family history. His grandparents were Holocaust survivors who lived only because they were sent to concentration camps relatively late in the war, in 1944. He frequently read interviews with people who saved Jews during the Nazi occupation, or with other heroic human rights defenders, and was struck by certain similarities.

Interviewers would ask questions such as, “Why were you willing to take those risks?” and invariably the reply would be along the lines of, “I just did what anyone in my position would do.” Kohen observed when we spoke via Zoom: “That’s just not correct, right? That’s just mathematically and empirically wrong!” It was rare for non-Jews to help their Jewish neighbours; dictatorships depend on the complicity of the majority.

Kohen began to delve deeper into the psychology of heroism. He wondered if understanding heroism might encourage more heroic behaviour, and if in a world where more people are willing to make sacrifices on the behalf of others, we might, then, need fewer heroes. Kohen has been researching heroic behaviour since 2006, and in recent months has been conducting extensive interviews with whistle-blowers or people who have rescued strangers or disarmed a terrorist.

Kohen’s questions sometimes baffle his interviewees. After speaking for more than an hour with a man who tackled a gunman when he opened fire on a train from Amsterdam to Paris in 2015, Kohen asked if the man had any questions. “Yes,” he replied, “aren’t you going to ask me about what happened on the train?” But that, to Kohen, is the least interesting part. He wants to understand everything that leads up to the heroic moment, the character traits and life experiences that cause a person to step up rather than stand by.

The research is still ongoing, and the findings are preliminary, but they do appear to confirm some theoretical ideas Kohen and other researchers have been positing. One practical observation is that certain types of training make people more likely to step in to help strangers. To some extent that’s obvious: strong swimmers or former lifeguards are more likely to save people who are drowning; first aiders are more likely to perform CPR. Most of his interviewees also possessed what Kohen describes as a “heroic imagination”: as children they imagined themselves as the heroic characters they encountered in books and on TV, and as adults they imagined what they’d do in various terrifying situations. “They’re the kind of people who when they go to the movie theatre start looking where all the exits are,” Kohen said. Their instinct is always to think of worse-case scenarios and then work out what they’d do. “The interesting thing is that while there’s something unusual about someone who thinks that way, that’s something you could teach people to do.”

There are differences between various types of heroes, those who act in the spur of the moment and those who plan their actions carefully and are exposed to risks for a long period of time, like whistle-blowers. For example, when Kohen asks whistle-blowers if they have a favourite inspirational quote they provide one without hesitation. When he asks them if they have experience of standing out from the crowd they reply, “Oh, I never go along with the group.” But something that the heroes Kohen speaks to all share, is an “expansive sense of empathy”, he said. “They think of more people as being like them… and as a result, they are thinking of all these people as part of their circle of care, as people who could have requirements of them.” They are moved to help others because they view strangers as like them, in a specific and powerful way.

Research into people who helped Jews escape the Holocaust confirms the idea that empathy is central to understanding heroism. In the 1980s, researchers who conducted interviews with hundreds of people who helped Jews and hundreds of bystanders found that the heroes were no more likely than bystanders to have friends or associates who were Jewish, but they were more likely to possess an empathetic imagination and to view Jews as similar to them. Many of them had suffered or witnessed persecution before, which may have contributed to their empathetic understanding.

In a survey of this research, the psychologist Stephanie Fagin-Jones teases out other common features of those who helped rescue Jewish people during the Second World War: they were often autonomous and non-conformist; they possessed moral courage; they displayed a high degree of moral reasoning and moral responsibility; and they viewed their moral behaviour as integral to their self-identity. Fagin-Jones argues that parenting styles can play a significant role in fostering empathetic concern and cultivating a strong sense of moral identity. A 2018 study, however, suggested a possible link between heroism and psychopathy, two traits associated with boldness and fearlessness.

****

The research prompted me to phone my Libyan friend Asma Khalifa, who I knew had joined the first anti-Gaddafi protests in 2011. I’ve always admired her rare independence of mind: she would have been the same person wherever she was born or grew up, but it was her bad luck to be born in Eighties Libya. Her English, mostly self-taught, was near-perfect and she read Shakespeare for fun; she didn’t drink at parties but liked to go to them to seek out the kinds of conversations, about literature or politics, that would be hard to have anywhere else. I didn’t know when I first met her that she’d been smuggling banned books into Libya since she was a teenager.

In February 2011 one of Khalifa’s friends, and a fellow book-smuggler, was arrested and later killed by Gaddafi’s security forces – but this did not stop Khalifa from protesting. She continued to campaign for human rights even after Libya plunged into civil war and after becoming a target for Islamist militia. Khalifa thought that the heroic activists she’d met over the years had all shared three qualities: “Empathy, curiosity and then maybe a bit of ‘I don’t give a shit’.” When asked what motivated her to continue risking her own life in service of a higher cause, Khalifa replied, “it’s not one cause, per se, it’s less ideological. I think of the purpose as more a continuity of generations of human beings who wanted better, who wanted different, who wanted to improve.”

This notion of fellowship with some abstract community of people who want better, who want more, lingered with me. Perhaps the idea helps explain why the small and big acts of heroism we have witnessed during the pandemic feel so important and valuable to us, even when we acknowledge that, in addition to our gratitude, this heroism is worthy of rage because Covid-19 heroes are also exploited workers who have been failed by the state.

The pandemic has laid bare many social ills: the inequalities that have risen unchecked for years; our corporate culture’s callous disregard for the underpaid workers now shouldering unnecessary and deadly risks; a society so devoted to individual self-interest that the wearing of a mask to protect others from a solitary and suffocating death has been recast as an outrageous assault on some God-given freedom to cough unimpeded, to shed one’s viral load wherever one goes.

Perhaps we are drawn to stories of heroism in part because they help us imagine an alternative future, new forms of social solidarity and community. The sacrifices made by, say, poorly protected nurses caring for patients dying in isolation wards are simultaneously a manifestation of catastrophic government failings and a reminder that the best hope for our salvation is our capacity for love, compassion and altruistic self-sacrifice. If the virus is contained it will be thanks to acts of heroism both extraordinary and mundane, from Li Wenliang’s courageous whistle-blowing, to every individual decision to limit social contact, to maintain one’s distance, to wear a mask. Until then, we need more heroes.

Now listen to Sophie discuss the subject on the World Review podcast….

This article appears in the 22 Jul 2020 issue of the New Statesman, Summer special