When I was a child, in the early 1950s, much of the world map displayed on the classroom wall was still painted pink, depicting the “British empire, on which the sun never sets”. I learned to read from a primer called Little Black Sambo about a Tamil boy and his parents, Black Mumbo and Black Jumbo. The coronation of Queen Elizabeth, which I remember watching with our neighbours on a tiny television set in 1953, was the occasion for a magnificent display of the empire’s power and extent, with special attention paid to colonial figures such as the revered Sir Robert Menzies, prime minister of Australia, or the much-loved (and much-patronised) Queen Salote of Tonga. The Eagle boys’ magazine, edited by the Reverend Marcus Morris in a vain attempt to provide a respectable alternative to the Beano and Tiger, serialised comic strips about great imperial lives, including those of Cecil Rhodes and David Livingstone, who, I learned, were hugely appreciated by the Africans for trying to civilise them.

When my mother’s home-made marmalade ran out, usually in August, we bought Robinson’s Golden Shred, which came with a free miniature “golliwog” figure. In the late 1950s, after we got a TV set, we watched The Black and White Minstrel Show every week, in which George Mitchell’s white singers blacked up and accompanied their performances with stereotypical “black” gestures, body movements and Al Jolson accents – or at least, some kind of approximation to them (the show was enormously popular, winning audiences of more than 20 million at its height). Over dinner, I listened to my parents arguing with one of their schoolteacher friends over whether black people were further down the scale of evolution than whites, located somewhere in the vicinity of the apes, as their friend maintained, or perhaps a bit higher up.

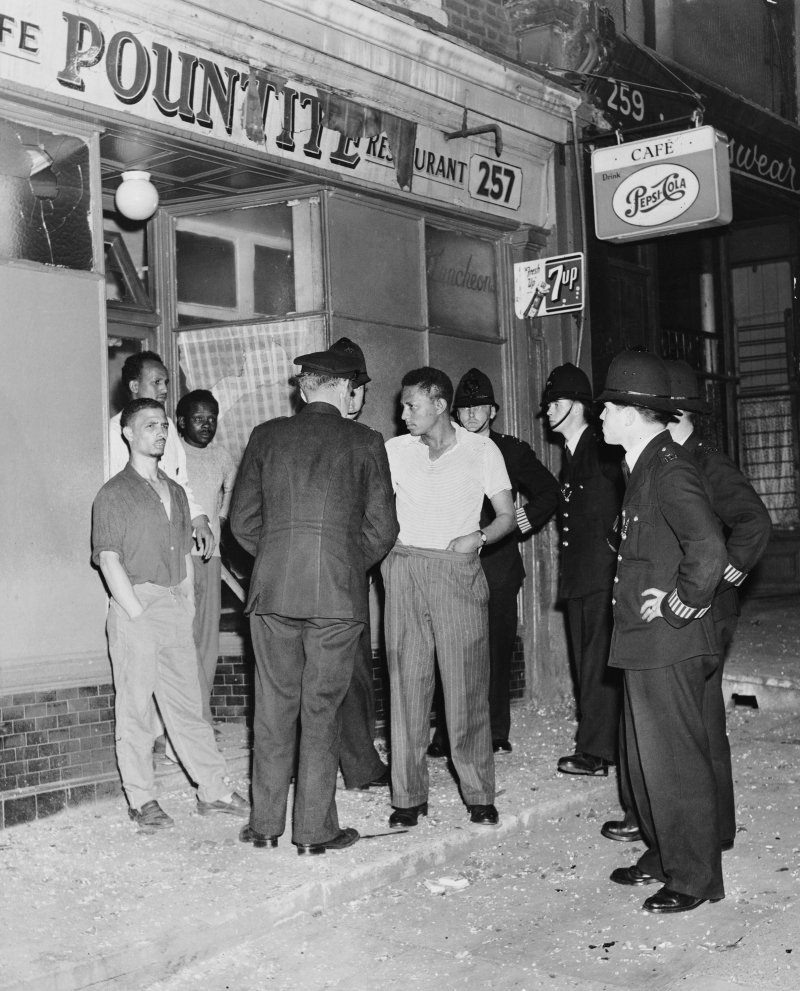

Unthinking racism was woven into the fabric of everyday life in Britain through the Fifties, accepted as part of the natural order of things for the great majority of white people. In the Notting Hill race riots of 1958, white working-class Teddy Boys assaulted black people on the streets and attacked their houses. In the Smethwick constituency in the West Midlands, the Conservative candidate at the parliamentary election of 1964, Peter Griffiths, fought on an openly racist platform – and won.

Under attack: policemen question locals outside a restaurant during the Notting Hill race riots, London, 2 September 1958. Credit: Scott Nelson/Getty

Open racism reached its apogee in Enoch Powell’s infamous “rivers of blood” speech in April 1968, with its vulgar racist language (“grinning piccaninnies”) and threats of violence, which prompted London dockers to down tools and march on Westminster waving banners with the slogan “Back Britain, not Black Britain”. An opinion poll conducted shortly after the speech showed 74 per cent approval for Powell’s attack on “coloured” immigration. Labour’s defeat in the 1970 election was widely attributed to the favourable reaction of significant parts of the white electorate to Powell’s words.

Many of my British contemporaries clearly still live in the cultural world framed by the British empire, which was built on the foundations of white supremacy and racial arrogance. According to an opinion survey carried out by YouGov in 2014 for the Times, 59 per cent of respondents in the UK thought the British empire was something to be proud of. Interestingly, by March 2020, this percentage had almost halved, and stood at 32 per cent. Clearly, a significant cultural shift has occurred.

Still, nostalgia for empire has been a significant factor in the minds of many Leave voters, 39 per cent of whom told the same recent survey they would like Britain still to have an empire, compared to 16 per cent of Remainers. Such fantasies find expression in the minds of some right-wing Conservatives, who think that pride in Britain’s long-vanished overseas empire should be part of the national identity.

But as these statistics indicate, there is no real agreement on how the memory of empire should be incorporated into the national identity. After all, in the same poll, 40 per cent of Leave voters did not want Britain still to have an empire. And the decline in retrospective imperial pride over the past few years surely reflects a more differentiated, more sophisticated attitude towards it.

****

What we remember as a society derives in the end from the kind of society we are, and reflects the kind of society we want to be. Britain’s cultural memory at the height of its imperial power – the late Victorian era, when so many of the statues now attracting attention were made – is not appropriate for Britain in the 21st century – a second-rank player on the world stage, a parliamentary democracy, and an advanced urban-industrial economy. Increasingly, we British are coming to realise this. We have also become a multicultural, multiracial society, displayed in its full glory at the 2012 London Olympics, an event that made me feel truly proud to be British.

Cultural memory finds solid expression with public statues, monuments and memorials. They are there to remind us of who we are, or better put, who we want to be, as a nation. It is an obvious point that some memorials are no longer fit for purpose.

One such is the statue of Edward Colston in Bristol, put up in 1895, at the height of British imperial pride and of the racist theories and practices that underpinned the empire. At the time, and for nearly a century afterwards, the statue reminded Bristolians of the philanthropic benefactions Colston had bestowed upon the city. Those who erected the statue did not concern themselves with how Colston had made his money.

But more recently the statue’s place in the city’s cultural memory has changed, and it has come to remind people of the fact that Colston made his fortune as a director of the Royal African Company, which, during this time, transported 84,000 enslaved men, women and children in degrading and inhuman conditions from Africa to the Americas; some 19,000 of them died of disease, malnutrition and mistreatment.

In an age when our revulsion against the treatment of people as less than human has grown, so too have protests against Colston’s glorification. Since the 1990s, Bristol City Council has considered a lengthy series of proposals to attach a plaque to the plinth describing his involvement in the slave trade. None of these has been accepted, however; delay followed delay, and on 7 June a crowd inflamed by worldwide anti-racist demonstrations triggered by the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis pulled the statue down and threw it into the harbour. For every black person who passed by it, the statue had justifiably become an affront. The police, wisely, did not intervene.

Following this, as protests spread across Europe, Tower Hamlets Council in east London removed a statue of the slave owner Robert Milligan from public display. In Belgium, statues of King Leopold II – who ran the Congo as a private fiefdom before the First World War, forcing African labourers to produce rubber, and whipping, mutilating and killing those who fell short of their quotas – have been defaced or removed. Names of people associated with the slave trade have been taken off buildings across Britain, for example that of Sir John Cass, the 17th-century slave trader after whom the Art School at London Metropolitan University is now no longer named. Embarrassed residents on a Bristol street named after Edward Colston have taped over his name on the road sign.

Pressure has been growing for some time across the world to take down statues of Cecil Rhodes – one has already been removed from the campus of the University of Cape Town. Rhodes, the imperialist’s imperialist, regarded black Africans as inferior, and made his vast fortune in the second half of the 19th century from employing African workers in his diamond mines in dangerous and degrading conditions. Rhodes also dispossessed and disfranchised the African population of the Cape on racial grounds when he was prime minister of the Cape Colony between 1890 and 1896. He declared Anglo-Saxons to be “the first race in the world”, and reasoned that “the more of the world we inhabit, the better it is for the human race”.

****

Like Colston, Rhodes was also a philanthropist. He left a large sum of money to set up scholarships to Oxford University for overseas students. However, they were only envisaged for men who belonged to the “Anglo-Saxon race”, who would in his vision form its intellectual elite. It’s worth pointing out that by this, Rhodes meant not only the white American, Canadian, South African, Australian and New Zealand men of the empire and the Anglosphere, but also Germans.

Rhodes stipulated in his will that race was no reason for exclusion from the scholarships. However, the scholars had to have Latin and Ancient Greek and nobody thought that black Africans or African Americans could pass this test. The selectors did not interview candidates at the time, and when a Harvard student who did have these languages, Alain Leroy Locke, son of freeborn African Americans, applied, his brilliance ensured he was admitted. By the time he arrived in Oxford, in 1907, it was too late to rectify the misunderstanding. Locke graduated in 1910, and went on to become an influential philosopher and the effective founder of the Harlem Renaissance.

The selectors did not make the same mistake twice, and it was not until 1963 before the next black candidate was awarded a place. The Rhodes Trust has reformed itself many times since, and in most respects no longer resembles the institution Rhodes founded. Surely, then, the time is ripe to rename it? More immediately, the removal of Rhodes’s statue from the front portal of Oriel College in Oxford, where it was put in 1911, is long overdue: the college dons need to think about what kind of message it sends to the people who pass beneath it, and what kind of man it was whose memory they are asking them to celebrate.

Rhodes is far from being the only target of protesters. There is a movement to take down the statue of Oliver Cromwell – the leading parliamentarian general during the English Civil War of the 17th century, signatory of the death warrant of King Charles I, and Lord Protector of England during the Interregnum – from its current place outside the House of Commons in Westminster.

When it was erected in 1899 the statue was criticised by monarchists, but their protests counted for little. This was the heyday of the “Whig theory of history”, according to which the fight for parliamentary democracy and the limitation of royal powers had been carried on through the centuries by men such as Cromwell, culminating in the late Victorian era.

In recent years, many if not most historians have come to consider him a religious fanatic who imposed Puritanism on the country through a military dictatorship. And in the 21st century, he is remembered for genocide in the ruthless massacres he administered in Ireland – a point also made by Irish MPs when the statue was originally approved by parliament.

In the post-Holocaust era, when genocide has rightly taken a central position in public memory, and the Whig theory of historical progress has been thoroughly discredited, surely Cromwell’s display in front of parliament is no longer justified. The statue was the creation of specific historical circumstances, and so too is the justification for its removal, since those circumstances no longer obtain.

Other statues in Britain have come under fire from the Black Lives Matter movement. One of them is the statue in Shrewsbury of “Clive of India”, the celebration of whose military achievements Michael Gove was so keen to make a compulsory part of the national history curriculum in our schools when he was education secretary under David Cameron.

The mid-Victorian sculpture, celebrating the founder of the British empire in India and the leading general of the East India Company in its wars with Indian states, was yet another product of the imperial age. But Clive looks anything but heroic today: indeed, he was widely regarded as a very poor advertisement for British imperialism in his own time. When Clive died at the age of 49 in 1774, Dr Samuel Johnson concluded that he had committed suicide, racked by guilt at having “acquired his fortune by such crimes that his consciousness of them impelled him to cut his own throat”.

****

It is worth recalling that toppling statues has a long history. It happens when public memory and public opinion experience major transformations, as in the French Revolution from 1789. In October 1793, gothic sculptures of the Kings of Judah were removed from the facade of Notre Dame in Paris by revolutionaries who thought they represented kings of France. Dragged on to Cathedral Square, the figures were formally guillotined, and the rubble sold to a builder; he in turn sold the heads to a royalist, who buried them. They were not rediscovered until construction work unearthed them in 1977. In Germany in 1945, after the fall of the Third Reich, Nazi monuments were pulled down everywhere, either by Allied troops or by Germans themselves. Streets named after Hitler were hurriedly given back their old names, and Nazi buildings, or at least those not already destroyed in the war, were demolished. In Iraq, statues of Saddam Hussein were toppled after his defeat in the war of 2003. Pulling down statues has often been a celebration of liberation from the tyrannies they represent.

Catharsis: a boy cheers as a statue of Saddam Hussein is set ablaze in Baghdad, 12 April 2003. Credit: Scott Nelson/Getty

But it’s not necessarily as simple as that. Some figures from the past elicit contradictory reactions in the present. This has been most obvious in the case of Winston Churchill, who as wartime prime minister rallied Britain in the fight against Hitler. After someone sprayed “was a racist” on the plinth of his statue in Parliament Square during a Black Lives Matter protest, far-right gangs descended on London on 13 June with the declared aim of defending the statue, which had been boarded up. Some attacked the police, while others were filmed making Nazi salutes. Clearly, this is a statue that means different things to different people.

And then, some politicians change their views over time: does William Gladstone’s youthful support for his father, a slave-owner in the West Indies, invalidate his later record as a Liberal reformer? Do we want to remember him as a defender of slavery or a champion of Irish Home Rule? Sometimes, historical figures are too controversial to justify commemoration. Westminster City Council, for example, in 2018 decided not to erect a public statue of Margaret Thatcher because although she was admired, she was also widely detested: another statue of the former PM, in London’s Guildhall, was decapitated by an angry critic only a few months after it was put up in 2002. The statue planned for erection in her home town of Grantham in Lincolnshire is still in storage.

Condemnations of the removal of statues in Britain in the past few weeks have not been slow in coming. “Do we want simply to remove them from the public record, from a public presence and public reference?” asked the ancient historian Mary Beard. Responding to the “Rhodes Must Fall” campaign, Oxford University’s vice-chancellor Louise Richardson has warned that to take down his statue would be “hiding our history”. Boris Johnson tweeted on 12 June: “We cannot now try to edit or censor our past. We cannot pretend to have a different history. The statues in our cities and towns were put up by previous generations. They had different perspectives, different understandings of right and wrong. But those statues teach us about our past, with all its faults. To tear them down would be to lie about our history, and impoverish the education of generations to come.” Charles Moore, like Johnson a former editor of the Spectator, has charged the Black Lives Matter movement with “an attempt to impose a single, organised, hostile narrative on this country. It wants literally to efface our rich national story.” The iconoclasts, apparently, believe “that our citizens, black or white, should be taught to hate their country and knock down its monuments… they want Britishness disgraced. Already they are picking targets at the heart of our story – Nelson, Gladstone, Winston Churchill.”

****

But the last time I looked at one, the history books were not full of statues. Toppling monuments does not mean erasing history, as critics have claimed. Nor is putting them in a museum a way of removing them from public scrutiny – quite the reverse. Pulling down statues has nothing to do with history, and everything to do with memory.

Statues are about the present, not the past: they are about the values we want to celebrate through the people we regard as having represented them: that is why a statue of Nelson Mandela was put up in Parliament Square in 2007, or a statue of Nicholas Winton has recently been erected in Prague, where he rescued some 669 mostly Jewish children from the Nazis on the eve of the Second World War.

Politicians have often failed to recognise the distinction between history and memory. When he was education secretary in the coalition government from 2010 to 2014, Michael Gove wanted a new national history curriculum in the schools to emphasise the positive side of British – in practice, English – history in order to create a strong national consciousness in school students before they went out into the world. Heroes of empire, including Clive of India, were to be taught to the pupils as examples of British achievement, while the First World War was to be understood as a struggle between the democratic, freedom-loving British and the evil tyranny of the Kaiser (notwithstanding the fact that 40 per cent of the British troops who fought in it didn’t have the vote, and one of Britain’s main allies was tsarist Russia).

Gove’s simplistic collection of pseudo-patriotic myths met with almost universal derision from historians and from organisations such as the British Academy, the Historical Association (whose membership is largely made up of schoolteachers) and the Royal Historical Society, and he was forced to withdraw it in 2013.

Gove thought that history was a collection of supposedly patriotic facts that had to be crammed into students to engender in them a love of Britain. But it isn’t. Nor is it the kind of alternative parade of heroes of the left, from the Levellers to the Tolpuddle Martyrs, Keir Hardie and Aneurin Bevan, that Tony Benn used to want us to celebrate. This kind of approach shows a crass failure to understand what history is about.

History is an academic discipline, with its own rules and procedures. Teaching it in schools means getting pupils to read historical documents critically, assess interpretations of past events and processes intelligently, and make up their own minds about key historical topics so that, at the very least, they will emerge as independently thinking citizens when they leave school.

It is not the same as memory – not individual memory, that is, but national, or collective, or cultural memory. Nor is history a matter of awarding ticks and crosses to the people of the past, canonising some as heroes and damning others as villains. Arguing about whether the British empire was a Good Thing or a Bad Thing is puerile and has nothing to do with the serious study of the past: such crude moralising should have been disposed of forever by WC Sellar and RJ Yeatman’s withering satire on the school history textbooks of their own day, 1066 and All That (1930).

Of course, we need critical and enquiring study of the British empire in our schools. But the aim should be to understand it – why it came into being, how it sustained itself for so long, and how it come to an end (and yes, what role slavery played, and why it was abolished) – not to praise empire on the one hand or damn it on the other.

The real question, then, is whose history are statues commemorating? The people that Charles Moore is complaining about don’t hate Britain, they simply want Britain to have an alternative set of national memories. To draw an obvious parallel, just because the Germans have put up memorials to the victims of the Nazi regime that ruled the country from 1933 to 1945, that doesn’t mean they hate Germany, simply that they have a different vision of what Germany is from that of Hitler and his fellow-mass murderers, and want to proclaim this publicly. Moore may talk of “our story”, but he and Michael Gove and their ilk are the ones who want to impose a single, organised, one-sided narrative on this country.

Indeed, the desire to present the British empire in a wholly positive light has itself led to censoring and lying about the past: thousands upon thousands of official files documenting the final, bloodstained years of British rule in Kenya were systematically destroyed from 1961 on the orders of the then British government, to prevent details of massacres of villagers and acts of torture committed against Mau-Mau rebels from coming to light.

Many more thousands of files were hidden away for half a century in a secret Foreign Office archive to prevent historians from gaining access to them, in an act of suppression that was not only illegal but also, as an official enquiry put it in 2012, “scandalous”. This is the kind of action that damages history far more than the removal of statues.

****

We might learn from Germany about how to deal with physical reminders of a controversial past. In the north German port town of Bremen, for instance, a huge red-brick elephant was put up in a park in 1932, to commemorate the overseas colonies taken away from Germany by the Allies at the end of the First World War, and to symbolise the demand for their return. By the 1970s, however, historians had uncovered the German army’s genocide of thousands of the Herero and Nama inhabitants of German South-West Africa, now Namibia, in the conflict of 1904-08.

The solution was not to knock the elephant down, but to rededicate it in 1989 as an “anti-colonial memorial”, accompanied by a large bronze plaque explaining the nature of the atrocities and the history of the monument. Since the brick elephant isn’t offensive in itself, and even has a certain ponderous charm, this seems to have proved a satisfactory solution.

Pulling down a statue can strike a blow for the recalibration of public memory and the proclamation of a new national identity. But in the long run, it often does not settle anything. In February 1917 revolutionary crowds pushed over statues of the reigning tsar, Nicholas II, and imperial memorials were cleared away across Russia and its provinces. After that, the new Russia proclaimed by Lenin and Stalin generated its own, equally celebratory statuary.

Just over 70 years later, however, the fall of the Berlin Wall and the end of communist rule in eastern Europe were marked by the public toppling and removal of thousands of statues of Lenin and Stalin. Now, statues to the last tsar, canonised by the Russian Orthodox Church in 2000, are going up again. More than two dozen memorials to Nicholas II have been unveiled in recent years. There have been reports of one statue shedding tears, and possessing healing powers. The Russian city of Oryol has even inaugurated a new statue of Ivan the Terrible, a 16th-century tyrant who, apparently, has been unfairly treated by history.

Nor does the recalibration of public memory necessarily have real, practical consequences. A statue of Felix Dzerzhinsky, first head of the Soviet secret police, the Cheka (later KGB), which arrested millions of people, and imprisoned them in the camps of the “Gulag archipelago”, was put up in 1958 opposite the KGB’s headquarters in Moscow. In 1991, after the fall of communism, it was removed, leaving behind a memorial to the victims of the secret police.

But the secret police didn’t move out of the forbidding building, where so many victims of the communist regime had been tortured and shot. Now Russia is run by a former KGB officer, and while Stalin’s purges are a thing of the past, democratisation doesn’t seem to have got very far and the secret police’s influence is growing once again.

Pulling down statues of Saddam Hussein may have provided a brief moment of elation, but the disastrous history of Iraq since 2003 hasn’t given cause for further joy. The crowds who destroyed the Stalin Monument in Budapest in 1956 didn’t have to wait long before the repressive regime he had imposed on Hungary was restored. The Bremen elephant is still there, but so too is the vast hoard of imperial loot that you can find distributed across the state museums of Berlin. Nazi monuments were destroyed all over Germany in 1945, but compensating Hitler’s victims and their families was to take many decades. And for more than 40 years, East Germany was ruled by a Stalinist tyranny that attempted seriously to suppress the past and the German people’s responsibility for it, with the result that neo-Nazism is now rampant in Saxony and other former provinces of the GDR.

Rhodes may fall, along with Colston, and Milligan, and possibly others, but this achievement will remain symbolic until the real issues of racial discrimination, inequality and prejudice in our society have been addressed. Let us hope that the current wave of protests will have some practical impact on bringing the shameful maltreatment and neglect of the victims of the Grenfell Tower tragedy and the Windrush scandal to an end. But handling these issues by setting up yet another committee, as Boris Johnson has done, is not a good start.

Richard J Evans is regius professor emeritus of history at Cambridge University, and the author of “The Third Reich in History and Memory” (Abacus)

This article appears in the 17 Jun 2020 issue of the New Statesman, The History Wars