I cannot remember a time when Virginia did not mean to be a writer and I a painter,” Vanessa Bell wrote in “Notes on Virginia’s Childhood”. “It was a lucky arrangement for it meant that we went our own ways and one source of jealousy at any rate was absent.” Woolf’s own take on and relationship with the notion of making pictures was a bit more complex than Bell’s familial version here, quite another story. In “Three Pictures”, written in 1929, she speaks at length about our natural proclivity to reduce ourselves to fixed image, see others as reductive portraits of themselves, and in the essay she signalled her unease, and her own aesthetic desire to challenge preconceptions of image, to make other ways of seeing possible, and to bypass appearance, break down simplistic divides (especially trenchant social and class divides):

It is impossible that one should not see pictures; because if my father was a blacksmith and yours was a peer of the realm, we must needs be pictures to each other. We cannot possibly break out of the frame of the picture by speaking natural words. You see me leaning against the door of the smithy with a horseshoe in my hand and you think as you go by: “How picturesque!” I, seeing you sitting so much at your ease in the car, almost as if you were going to bow to the populace, think what a picture of old luxurious aristocratical England! We are both quite wrong in our judgements no doubts, but that is inevitable.

Credit: private collection/ Prismatic Pictures/ Bridgeman Images

Credit: private collection/ Prismatic Pictures/ Bridgeman Images

“Following Woolf’s notion that, as creative women, we ‘think back through our mothers’, the exhibition traces many of the vital and fluid connections that can be drawn between Woolf, her contemporaries, and those who share an affinity with her work – whether such connections be tangible, anecdotal, geographical or imagined.” That’s what it says both on the wall and in the catalogue of “Virginia Woolf: an exhibition inspired by her writings”. Tangibly, anecdotally, geographically, but with an imagination somewhat numbed or frozen, on a freezing train on a lovely sunny day, the day before the hottest April day in the UK for half a century, I was on my way to St Ives to see it at the Tate.

But I wasn’t thinking about Virginia Woolf, or my mother; right then I couldn’t have cared less about Woolf and affinities; I was thinking a lot instead about my brother Gordon, who died earlier this year, the first of the five of us to go, and of how I’d been on this same train line only six weeks before through the snow from the east, for his funeral.

Now it was bright spring beyond the tinted window and I was thinking all the way to Plymouth, where he taught at the university, of him and my sister-in-law, and of their kids grown into such fine young people; and the train came into their city, stopped, started up again, pushed on through it. There was the bridge; there was the place where he kept his little fishing boat Independence II moored. There it went. On we went.

Come on, Ali. St Ives, your first time there, and an exhibition that sounds good, thoughtful, inventive, radical. Filed somewhere at the back of my head I had Woolf’s thoughts about the place where language and the visual arts meet and don’t meet, from a foreword she wrote around 1930 to the catalogue of her sister Vanessa Bell’s show “Recent Paintings” – a typically witty and questioning piece, casually rubbishing one after the other what she saw as the detrimentality of gender-labelling in art, the equally wearisome stuff that gets in the way of artists who happen to be women, and the belittling and disempowering of women all across society.

What the foreword most suggests, though, is that through her sister’s art she discerned a place in our response to the visual that hasn’t much “truck with words”. She describes a picture by Bell of the Foundling Hospital in London, painted completely allegory-less – no narrative, no Dickensian insistence, no history – just a picture of a “fine 18th century house and an equally fine London plane tree”. In the art act, she says, “our emotion has been given the slip.” But equally, “our emotion has been returned to us… The room is charged with it.”

Emotion, etc. I looked out the window at a landscape dulled. Maybe the tinting was on my own eyes. I’d been having trouble caring much about any thinking, any language, anything, certainly with doing any of the work I’d promised anyone; it was like everything I’d done since my brother died I’d done blindfolded, shrugging my shoulders.

I got off the train at St Erth and the young and gentle ticket-conductor (who’d said, when he saw my ticket, “St Ives, nice”) told me to have a lovely time. I thanked him. I sat on a stone wall in the sun till the little connecting train arrived.

This train was warm from the sun. Its windows were open, like you can’t do with most trains any more. I knew a little bit about Woolf’s time in St Ives, how she’d spent her childhood holidays there and how those wonderful summers that she and her sister and her brothers and their whole extended family had had, roaming wild up and down the cliffs and rocks and along the shore, had ended when she was 12 or 13 at the death of her mother, and how, all her life, Cornwall had always been a place apart, a place of healing for her. Shrug of shoulders. I love Woolf, of course I do. But train or home, here or there, warm or cold, winter, spring, summer, it was all mush of a mushness to me, as her friend Katherine Mansfield once put it. Or, as she put it herself: life, death, etc.

The train ran along the coast, dark rocky landscape all up one side and open sea, blue-grey-green, smooth for miles on the other. Then that coast opened further, it turned to gold, the huge sky above it opened even wider, and what I saw was a lighthouse, a little nub of a thing, small for a lighthouse, out on a rock.

Oh dear God. It was the lighthouse. As in To the. Words, no words. It moved me. I burst into tears, surprised.

I hadn’t known that I gave a damn.

Human nature: Dora Carrington’s Spanish

Human nature: Dora Carrington’s Spanish

Landscape with Mountains (1924). Credit: Tate

Next day the sea mist was in. It was 29 degrees in London, 12 degrees in St Ives. I walked to the Tate, the sea spread out before it, the sloping old graveyard with its skewy headstones next to it. With any luck it’ll be warmer in a couple of hours when I’ve seen this, I thought.

I came out about six hours later, long enough for the temperature to hit 16 degrees and nowhere near long enough for an exhibition I could cheerfully have spent several days at.

It’s not that the exhibition is a stunner, or the best thing I’ve ever seen. On the contrary, it’s mixed, problematic, higglety-pigglety. But I haven’t stopped thinking about it since I saw it, its correspondences, its parallels, its communal ethos, its playfulness, its revelation of a shared and different family of possible languages.

It showcases – messily, provocatively, sometimes brilliantly – more than 250 works, dating from over 150 years to now, by more than 80 artists. It’s transferring next week from its Tate St Ives run to Pallant House in Chichester, not far from Monk’s House where Woolf lived much of her adult life, then later in the year to the Fitzwilliam in Cambridge, a city whose establishmentarian and exclusionary cultural authority she so joyfully lambasted in many of her works, especially A Room of One’s Own. It’s “not about Virginia Woolf’s life per se,” though; it “rather acknowledges the influence of her ideas on subsequent generations of artists and writers… Woolf’s exploration of equality and independence in her writings is pertinent to the ways in which artists in this exhibition investigate timely questions around identity, gender and the representation of the self.”

It says this in its catalogue, which is an informal publication, soft-backed, very colourful, and framed by sections that literally run artworks into other artworks, so that a double page spread of A Green Sea by Laura Knight (1918) meets a strip of Gluck sky and land from the edge of Cornwall Landscape (1968) and on the next page the rest of that Gluck picture rubs up against a wedge of Dorothy Brett’s Pond at Garsington (1919), which, to see fully, you turn the page, where it’s placed up against a strip of a Jane Simone Bussy landscape from around 1950, which in turn meets the jarring sky-hanging beast of Ithell Colquhoun’s Exposed on the Mountains of the Heart (1957), itself bordered over the page with part of Dora Carrington’s Spanish Landscape with Mountains (1924), which morphs from colour into black and white and becomes the contents page.

This makes working sense of what Hana Leaper says in her essay about the exhibition’s structure setting out to identify Woolf as “a catalyst and connector, and by no means a solitary figure writing into a void.” The exhibition aims, she writes, to embed “Woolf’s feats… within a sustained history of women creators and thinkers.”

But it’s a big relief to leave Judy Chicago’s Study for Virginia Woolf from The Dinner Party (1978) at the door, a work curtailed by words all right – some of them Woolf’s own (from her suicide letter), most of them Chicago’s – accompanying her figuring of Woolf as a vaginal open book, its pages curling like an artichoke or a mechanised peony. “Poor Virginia,” it says in handwriting in the corner. “She was a flower of delicacy, a genius, a shaking leaf – she [tottered? tattered?] on the brink of sanity – holding on long enough, often enough to speak with a true female voice which, like a beacon, beckons us.” Other verbal fragments: “she could not bear”, “her work and life”, “labour of so many”, “sex trampled under”, “angry footsteps”, “gone”. Thank God for Vanessa Bell’s Cornish Cottage (c 1900) hung along from it, slab-like and airy at once with all the inarticulable strangeness of our mercurial seeing of realities, and for her 1934 portrait too (very figurative, as if particularly interested in her substantiality) of a slightly disdainful Woolf holding a cigarette at what can only be called an angle with attitude, and the richness of the culture she’s created and been part of all around her, books piled up, books lining the shelves, the Omega-workshop-like abstracts in the rug at her feet. If there’s something this exhibition does in spades it’s dispel any notion of a “poor Virginia”; it’s a rich show, full of fun and all about the serious application of vitality, specifically revealing when it comes to the energy and vivacity in its lives and works, the invaluable work done and ground shifted by lives up against the odds.

Take Dora Carrington, whose lovely unruliness, blunt charm and gracefulness can’t not shine out of the photographs and the handwritten letters on display, full of mischief, life, love. Not that the dark times aren’t contextualised: in her painting Farm at Watendlath (1921) the woman and child in their white Edwardian dress have turned their backs on us, become caricatured and tiny, dwarfed by dark geometrics, the haunted-looking buildings with their cross-eyed look, their windows simultaneously gaping and shut, and looming above, shouldering out what little line of light there is, the mountains dwarfing all the human and social structures. Then there’s the surreal fecundity in her Spanish Landscape with Mountains (c 1924), spiky plants in the desert in front of hills that strain against their own surfaces as if to burst, like huge boils, in a landscape that’s so like body-parts, knees and breasts covered tight with skin or sheeting, that it cancels the human, makes us nothing but landscape after all.

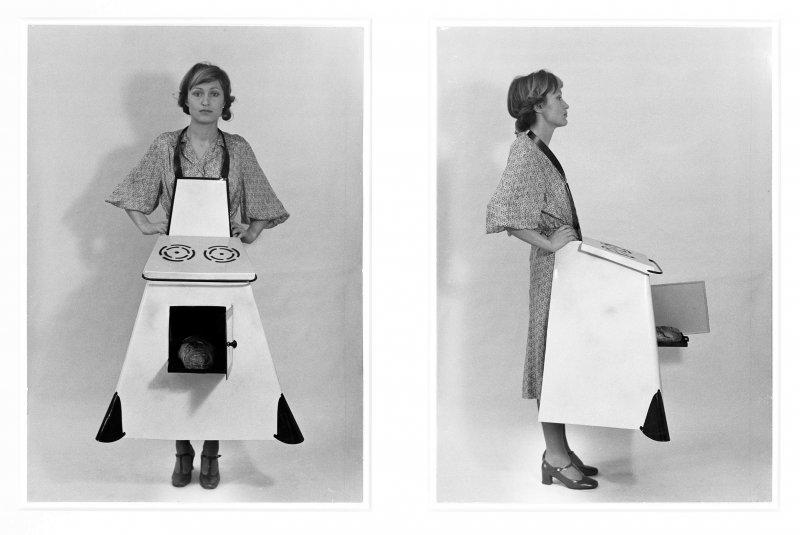

Woman’s work: Housewives’ Kitchen Apron (1975) by Birgit Jürgenssen. Credit: Alison Jacques Gallery, London and estate Birgit Jurgenssen, Vienna

Woman’s work: Housewives’ Kitchen Apron (1975) by Birgit Jürgenssen. Credit: Alison Jacques Gallery, London and estate Birgit Jurgenssen, Vienna

The exhibition just about manages to corral its works into four categories, exploring “Landscape and Place”, “Still Life, The Home and ‘A Room of One’s Own’”, and “The Self in Public and Private”. Things spill over, though, refusing to be defined. At first, everything looks mismatched; some things shine, others look dated and flat, and what can Barbara Hepworth’s pristine, metallic Group of Three Magic Stones (1973) ever have to do with Eileen Agar’s spiky horny rotting Marine Object (1939)? It takes a moment before the formal pairing suddenly delivers, and you can see yourself in the reflective surface of Magic Stones while you wait. Marine Object, utterly refuting reflection itself, is reflected in the Hepworth sculpture too. But then, because work and observer are both reflections, the unlikely affinity shifts Magic Stones into a version of Marine Object – and vice versa. The notion of reflection changes, becomes the opposite of self-interest or vanity. It remembers its root in thoughtfulness, consideration.

It’s a thrill to see (my first time) a work in the flesh by Dorothy Brett, a shifting Cézanne-like layering of depths and lights and darks, and to see the real and deep tonal richness in the works by Laura Knight; it’s almost as if her Autumn Sunlight, Sennen Cove (c 1922) has a fight to pick with Carrington’s Farm at Watendlath, about ways in which to see the just-postwar world: Sennen Cove is edgy, examines what the edge of this country now means by placing three blatantly happy-looking picture-book children (and a donkey, a conscious ameliorisation narrative) foreground to a massive sweep and fall-away of landscape with someone struggling to move a cart up a steep hill, incidental, far down in the distance. Something in the correspondence between them is very like the argument Woolf had with her friend and rival Mansfield who, disappointed by the so-called realism in Woolf’s second novel Night and Day (1919) – a realism that rang untrue to her and preserved that novel as formally unshaken by the just-finished war – wrote a searing review of the book, declaring it elegant but hopelessly dated. Woolf, furious, boiled in her anger. But the next novel she wrote, the first of her great experimental transformations of the form, was Jacob’s Room (1922), an unsettled and fragmentary elegy, all breakage and looming absence, and about the beginning of the end of the empire.

Interiors open again and again through the show. Of the contemporary works, which can just occasionally render the curatorial take on Woolf’s project a bit surface-deep, the Sara Barker pieces really benefit from and nourish contextualisation; they’re playful, broken, mirror-fragmented, patched, jagged and improvised; and next to a Vanessa Bell window opening to a pond in which a fence bends in reflection into very Barker-like lines, something authentically familial in form is revealed. Of the film work, Joan Jonas’s Songdelay is far and away the gift, a good-humoured beauty, proving, very Woolfily, that given very little we’ll make rhythm and pattern, and given a blasted landscape we’ll make a dance of it.

In fact it’s when the exhibition lets Woolf go, doesn’t fuss with quotes or inferences, that Woolf most appears in it and the curation comes together, especially via one or two brilliant choices. Hang Birgit Jürgenssen’s 10 Days – 100 Photos (1980-81) – all animal masks, skulls, informal ceremony, shamanic re-seeing of the possibility of the body – between Ethel Walker’s perky, dandyish 1925 self-portrait and Romaine Brooks’s The White Bird (1908) – in which a bird in a cage looks out at a woman dressed in white, but dark, ghostly, insubstantial, with a great red something in her hat (a feather?) making the only spot of bright colour in the painting other than the bird’s beak – and everything becomes possible. “It is difficult to place Virginia Woolf,” Jean Mills writes in the catalogue, “to put her here or there, to frame her for the purposes of exhibition, to contain, shelve, bury, or even elevate her on a pedestal, as she was often uncertain and suspicious of boundaries.” Brooks’s turn of the century woman is poised here on a carpet that looks ephemeral, like the ground beneath her feet is going to give way any moment and at the same time has fixed her, trapped, on a shimmering pillar of nothing. But she has her fist clenched at the heart of the picture and there’s a vision of this fury too in the prone woman reflecting herself upright and beyond the bed and fabrics in Zanele Muholi’s Bona, Charlottesville (2015); a determination in it that heartens and fleshes out where we are in history right now, making profound contemporary sense while also nodding, familial, towards Brooks’s White Bird. There’s the apprehension and fear in Gluck’s portraits, the witty liberation in Jürgenssen’s spelling-out with her body and her spirit what a woman is and isn’t, in Frau (1972) and Housewives’ Kitchen Apron (1975), and then there’s Agnes Martin’s reveille, Morning (1965), meditative, disciplined, rigorous, mind-expanding, and I’ve hardly scraped the surface of the show.

“For masterpieces are not single and solitary births; they are the outcome of many years of thinking in common, of thinking by the body of the people, so that the experience of the mass is behind the single voice”: that’s Woolf, in A Room of One’s Own. This exhibition does what it says on the tin. Inspired by Woolf, it can do anything it likes, go anywhere it likes, and it does it thinkingly, ever open and connective. This gives it a restless air and a breadth of fresh air. It’s simultaneously too big and too small. This isn’t a criticism, it’s a historical spatial conundrum. It comes together against the odds. I’m not quite sure how, but it does.

That, in itself, sent me home from St Ives less mournful, more open, more accompanied, less cynical. It sent me from the cold to the warm again, returned me to more than myself, because there’s almost nobody who writes as well as Woolf about mortality, and about the intellectual conditions of our existence, of our really and truly being here while we’re here, and the curation of the exhibition more than understands this.

I don’t know if it exactly left me thinking back through my mother, though it gave me a fair few things I wish like anything I could talk with her about. But I know I came to St Ives desolate for family, and that I left it inspired, myself, on its route map of

extended family.

“Virginia Woolf: An Exhibition Inspired by Her Writings” is at Pallant House Gallery, Sussex, until 16 September, and then Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, from 2 October to 9 December

This article appears in the 23 May 2018 issue of the New Statesman, Age of the strongman