If parliament defies the government and blocks a “hard” Brexit, a specific group of four million voters, identified by new research, deserves much of the credit – or the blame. These people voted to leave the European Union in 2016 but did not vote in this year’s general election. Had they turned out and voted in the same way as other pro-Brexit voters, the Conservatives would have won around 30 extra seats and a comfortable majority in the House of Commons.

The fact that one in four Brexit supporters stayed at home this June emerges from the largest ever panel study of its kind. YouGov tracked the voting decisions of the same 50,000 people at the time of the 2015 and 2017 general elections, as well as last year’s referendum. As a result, YouGov has been able to monitor voters changing their minds. The exceptional size of the sample allows us to examine the voting behaviour of different groups in granular detail. The New Statesman has been given exclusive access to the data, which provides an unrivalled insight into the factors that have led to today’s crisis over the future of the United Kingdom.

What emerges is a picture of unprecedented turbulence, which helps to explain why historically blue seats such as Canterbury – Conservative since it was formed in 1918 – fell to Labour, while established Labour strongholds such as Mansfield and Stoke-on-Trent South went Tory.

YouGov’s data shows that as many as 1.1 million voters, mainly pro-EU Remainers, switched directly from Conservative to Labour, while 850,000, mainly Leavers, made the opposite move. All together, ten million of the 30 million people who voted in 2015 either changed party or abstained this year. Here are ten key findings from YouGov’s research.

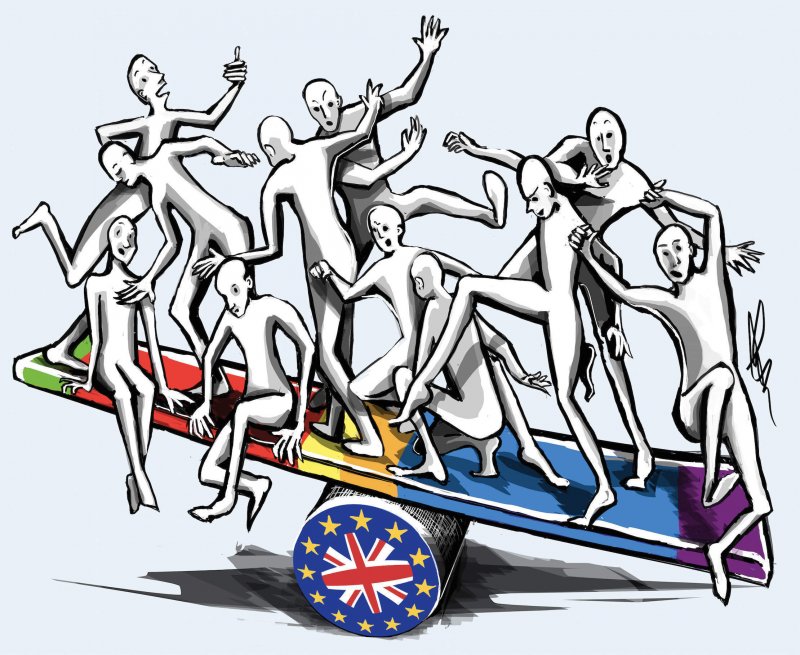

Picture: Ella Barron for the New Statesman

More Remainers than Leavers voted in the 2017 general election

In last year’s EU referendum, approximately 17.4 million voted Leave, while 16.1 million voted Remain. The abstention rate among Leavers in the 2017 general election was twice as high as among Remainers. As a result, 14 million Remainers voted this year, compared with 13 million Leavers.

The abstention rates were especially high in two specific groups. Of the 3.9 million people who voted Ukip in 2015, 30 per cent, or almost 1.2 million, did not vote this year. In addition, of the five million non-voters in 2015 who took part in last year’s referendum, more than three million stayed at home in 2017, two-thirds of them Leavers.

It looks as if, for many people, the chance to vote on Europe was a one-off opportunity to decide the nation’s future, rather than the start of a continuing engagement with politics.

The Conservatives fell short among former Ukip supporters and Leavers who hadn’t voted in 2015

The abstention rate among Leavers does much to explain how the Conservatives blew this year’s election. The Ukip vote did indeed collapse, as the Tories hoped – from 12.6 per cent in 2015 to 1.8 per cent in 2017. The party could not even match the 1.9 per cent that the BNP won in 2010. But, as the table below shows, the Conservatives attracted fewer than half of Ukip’s supporters. With Labour picking up 12 per cent of Ukip’s 2015 vote (more than the number of those who stayed loyal to Ukip), the net advantage to the Tories in Conservative-Labour contests was just 4 per cent of the nationwide vote.

The Tories also failed dismally among those who had abstained in 2015 but voted Leave last year. Theresa May’s promise that “Brexit means Brexit” might have been expected to win over much of this group. But it didn’t. Just 19 per cent voted Conservative this June. Labour, with 12 per cent, was not far behind.

Both main parties suffered considerable Brexit-related defections – Conservatives among Remainers, Labour among Leavers

Europe was a dividing line for the supporters of both Labour and the Conservatives. Desertions took place on a large scale among Conservative Remainers and Labour Leavers. As many as 25 per cent of those who voted Conservative in 2015 and Remain last year switched to another party, mostly to Labour. A further 12 per cent abstained this year.

Likewise, 22 per cent of Labour Leavers switched party, the great majority to the Tories, while only 11 per cent of Labour Remainers took their vote elsewhere. As concerning to Labour is that as many as 21 per cent of Labour Leavers abstained this year, compared with just 8 per cent of Labour Remainers. These stay-at-home Leavers may well have tipped the balance against Labour in three constituencies that the Conservatives gained from Labour on relatively low turnouts – Mansfield, Middlesbrough South and East Cleveland, and Stoke-on-Trent South – and denied Labour victory in at least six seats that it hoped to gain.

Those nine seats saved Theresa May’s premiership. Had Labour won them all, she could not have secured a majority in parliament, even with the support of Northern Ireland’s Democratic Unionists.

Most of Labour’s 10-point rise in support came at the expense of smaller parties

While the Tories did less well than they hoped among former Ukip supporters, Labour beat expectations among those who voted for smaller parties two years ago. We have already seen that more 2015 Ukip supporters switched to Labour this time than stayed loyal. The same is true of those who voted Green and Plaid Cymru in 2015. Among the 1.2 million who voted Green two years ago, 650,000 switched to Labour this year, while only 130,000 stayed with the Greens. Labour gained two million votes from smaller parties, neutralising any Conservative gains from Ukip. This delivered two-thirds of Labour’s 10-point surge across Britain.

Almost half of those who supported the SNP in 2015 deserted it this year

The SNP is in even deeper trouble than the raw results suggested. YouGov’s data shows that only 55 per cent of people who voted SNP in 2015 stayed loyal this year. The other 45 per cent divided equally into those who voted for a rival party and those who stayed at home. Indeed, the SNP lost a higher share of its support to abstention than any other party with MPs in the new parliament.

This high abstention rate is a sure sign of a party in difficulty. It explains why Scotland was the only part of the UK with a fall in turnout, from 71 to 66 per cent. It looks as if the impressive 85 per cent turnout in its independence referendum three years ago, like the Brexit referendum across the UK, has failed to convert many former non-voters into long-term participants in subsequent elections.

The long-standing gender gap in British politics has been reversed, with women in their thirties and forties moving decisively towards Labour

For six decades, pollsters have been analysing the gender split at general elections. Until 1992, women were more likely than men to vote Conservative. From 1997 until 2015, the gender gap all but disappeared. This year, for the first time, women were significantly more likely than men to vote Labour. Among men, the Tories enjoyed a 6-point lead (45 to 39 per cent) – enough to give Theresa May a comfortable majority. Women divided evenly (43 to 43 per cent). On those figures, Jeremy Corbyn would now be prime minister.

The table below shows the two groups of women who swung most to Labour this year compared with men: full-time workers and women in their thirties. Many more women than men have modestly paid jobs in the public services, such as health and education; they have been hit harder than most by pay restraint, cuts in public-service funding and, more recently, the post-referendum rise in inflation.

As for women in their thirties, this is the group with young children that most precisely fits Theresa May’s description of “just about managing”, in terms of family finances and access to public services. Far from winning these women over with her concern, May has alienated them with the impact of her policies.

In the US, there has long been a substantial gender gap, with most women voting Democrat and most men voting Republican. With the decline in Labour’s male-dominated culture, rooted in the big industries and trade unions of the mid-20th century, is Britain heading in the same direction?

Social class has ceased to be the decisive influence on party loyalties

Fifty years ago, the political scientist Peter Pulzer wrote: “Class is the basis of British party politics; all else is embellishment and detail.” No longer. While the gender gap has widened, the class gap has closed. This year’s election smashed two records. Labour’s support among professional and managerial “AB” voters this year was 38 per cent – up 8 points compared with two years ago and higher even than in Tony Blair’s landslide victory of 1997. In contrast, the Tories did substantially better among semi- and unskilled “DE” voters than in Margaret Thatcher’s landslide of 1983.

The Brexit debate has played a significant role in a range of demographic shifts. However, Brexit alone does not explain the narrowing class gap. Labour’s weakening support among working-class voters is not new. The long-term loss of industrial jobs has shrunk Labour’s historical electoral base. Brexit has accelerated an existing trend, not created it.

The big dividing lines this year were age, education and attitudes to Europe

The wider impact of Brexit on Britain’s electoral demographics is hard to overstate. Young voters and graduates strongly favoured staying in the EU in the referendum and notably swung to Labour this year. Older voters who left school at 15 or 16 plumped for Brexit last year, and those who voted at all went Tory this year.

There is nothing new about different groups producing varying swings. In 1979, Margaret Thatcher was propelled to power by a big swing among skilled manual workers. But never have the swings varied so wildly as this year, with major swings to Labour among some groups, and equally major swings to the Conservative Party among others. The last time Labour’s vote rose sharply, in 1997, the Tories lost ground in every demographic group. Not this time.

The opposing swings at the opposite ends of the class spectrum were largely driven by Brexit, with “ABC1” Remainers swinging Labour’s way, and “C2DE” Leavers shifting to the Tories. This suggests that the class gap might widen again if and when Europe ceases to dominate domestic politics – unless, that is, the impact of the Brexit debate has been to produce a lasting shift in Britain’s political culture. By 2030, we should know.

Jeremy Corbyn’s promise to “deal with” the debts of former students did not boost Labour’s vote

YouGov’s data debunks one myth about the election – that Corbyn’s promise boosted Labour’s support among graduates in their twenties. It is true that Labour’s vote rose among such voters by a remarkable 21 points, from 44 per cent in 2015 to 65 per cent this year. But these figures – both the levels and the changes – are almost identical among those who never got beyond A-level and also among those whose education ended with GCSEs. Labour did very well among the under-thirties, regardless of whether or not they were debt-burdened graduates.

The impact of education kicked in among the over-thirties. For those born before 1987, there was almost no swing to Labour among people with no qualifications higher than GCSE, but there was a big shift among graduates, with the Tories down 6 per cent since 2015 and Labour up 16 per cent.

The challenge facing Labour next time is greater than it looks

Few political sentiments are more seductive than “one more heave”. Labour’s 41 per cent was the highest share received by an opposition party since 1970. It would take only a modest further shift for the party to win next time. The question is: where will these votes come from? There seem to be few Lib Dem, Green or Ukip voters left to squeeze. Labour would do well to hold on to all the younger voters and the older, better-educated voters, whose choice this year was largely driven by opposition to Brexit.

The one significant opportunity for Labour is the group with whom it most underperformed this year: working-class voters, especially in the Midlands and the north of England. These are the constituencies that Labour must win back if its leader is to enter Downing Street within the next ten years. But can the party find a way to appeal to the pro-Brexit voters who deserted it in these crucial seats, while retaining the loyalty of the anti-Brexit voters it harvested this year with such effect?

This article appears in the 27 Sep 2017 issue of the New Statesman, The Tory tragedy