Foreign policy rarely wins a national election. However, in hosting the G20 summit on 9 and 10 September, India’s prime minister Narendra Modi sought to do precisely that. India postponed the taking of the G20 presidency by a year and tied its moment in the sun to the domestic calendar of national elections. In early 2024, Modi will seek a third term and this global marquee event was mobilised to further amplify Modi’s image, brand and persona as he continues to enjoy high approval ratings.

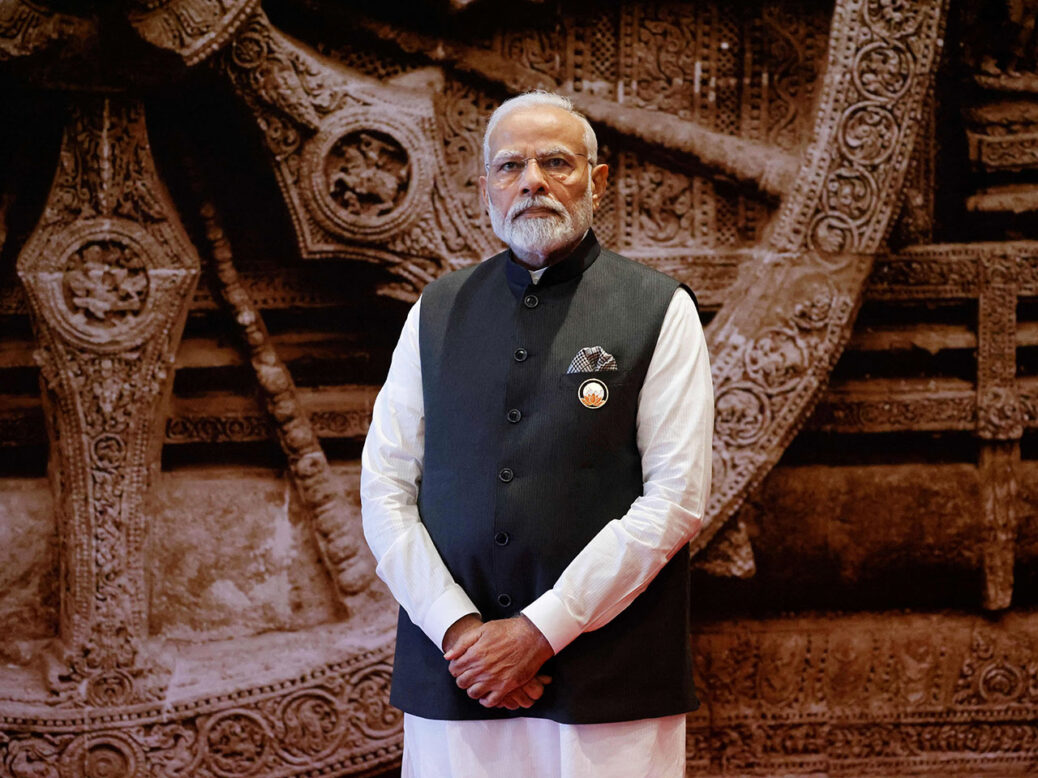

Leaving nothing to the imagination, the lotus – the symbol of India’s ruling party – was chosen as the logo of the Delhi summit. Delhi’s spacious boulevards were awash with outsized hoardings of Modi looming large over world leaders and the cityscape. If it felt and looked like a political campaign, then it also invited questions about India’s new and transformed identity, both at home and the world, which has been recast by Modi’s strongman signature.

Despite all the glitz and pageantry, and above all the careful timing, the summit arrived at a turbulent time. With Russia’s Vladimir Putin and more significantly China’s Xi Jinping giving the Delhi meet a miss, India’s chosen strapline for the summit of “One world, one family” might just serve as an epithet to a short-lived era of multilateralism that the G20, arguably, sought to reflect.

Under Modi, transactionalism as opposed to values has emerged as the driving principle of India’s relations with the world. While there is no official outing of a new “India way”, even a cursory glance at the country’s newspapers – to say nothing of India’s strategic and think-tank constellation – attests to a “realist” foreign policy outlook. National self-interest rather than any grand vision of harmony, despite the summit’s tagline, have defined India’s new global avatar. This is not just about Ukraine. India, of course, remains “neutral” even as it continues to buy oil and much else from Russia.

In the aftermath of the post-pandemic order and its polycrisis, the original, financial crisis of this century – 2008, when the annual G20 summit was launched – seems if not simple in comparison, then certainly distant. The widening chasm between China and the West has not only worn out the old certainties of “blocs” and “alliances” but has also created flux. Crucially, the once explicit but contested norms and ideologies of international relations seem to have vanished. It is hard to galvanise the world into any ideological fight, least of all in the name of liberal internationalism, as its brutalities and hypocrisies have run out of fig leaves.

Global turbulence is being navigated by India’s insistence that the world is “multipolar”, as it downplays the rising bipolarity of America and China. India seeks to leverage this language to position its own status as a player. India seeks to project itself as a bridge in the new and competitive arena of emerging multilaterals, as they vie for relevance, if not supremacy. As such, India is a leading member of the US-conceived G20, the Global South-oriented Brics (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa), and also a member of China’s very own Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO). These multilaterals not only reflect new realities but are effectively making the Cold War architecture of global governance redundant.

As strategic currency “multipolarity” arguably masks India’s increasing lack of choice. For one, India’s bilateral relations with China are more than simply strained, with India’s hawkish external affairs minister S Jaishankar going as far as to describe them as “abnormal”. Relations between these so-called Asian titans have crumbled since May 2020 when hostile combat between the two broke out in Galwan on the Himalayan peaks of their long border. The dispute shows little sign of reaching entente, let alone resolution.

Equally, India’s deepening engagement with America was on display during President Joe Biden’s bilateral talks with Modi on the eve of the summit in Delhi. This took place shortly after Modi’s state visit to America in June. Strikingly, rather than the much-vaunted values, it is trade and military transactions that now underpin relations between the world’s most powerful nation and the largest democracy, which the US and India, respectively, are.

[See also: The Sunak-Modi bilateral]

Precisely because it is not China, India today is being cast as a pivot that will not only redirect but help overcome the global polycrisis of our times. It is tagged as a “rising power” and a “swing state”. Sitting between China and America may give India strategic salience, but such a location is also riven with risk. It might continue to buy arms from Russia while conducting military exercises with America in the Indo-Pacific, but ultimately India can only defer, not control when its transactional multipolarity comes to an end. That moment can be decided by others.

With Xi Jinping’s absence at the summit, China marked its polar presence in world affairs. As the Brics summit in South Africa in August indicated, China is trying to turn away from the West and focus on the Global South. China has emerged as the leader of the Brics grouping, which extended its membership to include new allies Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. Tellingly, India has projected itself as a voice of the Global South, with “inclusivity” a key buzzword of the Delhi summit.

Multipolarity has nevertheless displaced the long-held Nehruvian ideals of “non-alignment” that once defined India’s global identity. Non-alignment propelled India’s leadership of the Global South and newly decolonised countries in the Cold War era. Yet, for all its pragmatic power, India’s new-found realism or transactionalism arguably may not be sufficient, let alone a winning strategy. Many countries in the Global South today – such as Vietnam, Indonesia and Malaysia – are competitors rather than ideological allies. Non-alignment, at the very least, symbolically managed to reduce competition.

As its active courting by Brics and the G20 indicate, the Global South could fragment – with some nations potentially aligning with the West, while others turn away – at the very moment its collective bargaining position reaches a peak. To this end, for India the success of the G20 summit was largely staked on whether its desire to induct the African Union (AU) as a member was realised — a goal that was reached at the outset of the summit, when a triumphant Modi invited the AU chair to take a seat at the leaders’ table as a permanent member. But even as Modi projects a united world family, critics of the Indian prime minister’s domestic politics will note that he has replaced diversity with division.

International press and opinion have been consistently firm in pointing out the hypocrisy, if not contradiction, in pursuing world unity as India itself becomes increasingly divided after nine years of Modi rule. From India’s “democratic backsliding” to the violent discrimination against its Muslim minority through routine and extraordinary violence and the erosion of its once robust and free media, India under Modi is no longer considered an exemplar of multicultural democracy.

Critics of Modi’s politics face the sharp wedge of the state’s coercive power and authority, whether they are academics, movie stars or elite athletes. Leaders and workers of India’s opposition parties are routinely ensnared in legal battles, whether over defamation or corruption, as the full force of government agencies is unleashed to silence political contestation and dissent.

In countering the growing, negative global image, Modi and his acolytes deploy the rhetoric of decolonisation and civilisational grandeur in India’s own high-octane culture wars. India’s domestic identity now distils and embodies the contemporary contours of global democracy in which personality, populism and neo-nationalism reign over a dynamic but highly unequal economy. For all its grand claims of exceptionalism, India’s democracy looks more like both an illiberal Hungary and a polarised America.

Yet India has become the country most courted by the West. That India is not China only partly explains it. Democracy has long been India’s strongest asset on the world stage and is key to its considerable soft power. Instead, it is now India’s scale that has emerged as a stronger calling card. With the largest and youngest population and the fifth-largest economy, tipped to grow faster than any other, pragmatism if not cynicism has come to define the West’s relationship to India.

Anyone who looked behind the snazzy hoardings of Modi at the summit will have found that India’s once divided and fragmented opposition parties have forged an unprecedented, united front to try to deny Modi a third term. They have already laid claim on Modi’s growing monopoly on nationalism as the coalition has inventively and cannily called itself INDIA (Indian National Developmental Inclusive Alliance).

In response Modi and his party have ignited political headlines with rumours that the country could be officially renamed Bharat, as derived from its Sanskrit and epic traditions. The rumour started with the official G20 dinner invitation sent by the prime minister, which invoked Bharat as the country’s name. Modi then opened the G20 summit sitting behind a sign reading Bharat. The gesture is a powerful, if confusing, reaction that attests to the fact that India’s opposition might just have unsettled Modi, even as he enjoys high personal ratings. At stake is more than a name but the country’s identity. And the consequences will be global.

In blurring the national with the international, and the global with the parochial, Modi has cast himself as a guide to the world. But it will be Indians who determine the precise shape and direction of democracy. If India’s scale represents the global in the miniature form, then the importance of India on the world stage will lie in the fate of democracy as a global good.

After nearly a decade of its capture by Modi, India finally seems ready to fight back. The upcoming 2024 election is pitched as a contest between authority and justice, diversity and division. It is India’s domestic version of the contest between idealism and realism.

Unlike most easily forgotten summits, Delhi’s G20 presidency will be recognised as historically significant – when all the sources of global and national scission were exposed in such a way that even the most popular leader in the world could neither contain nor hide them.

[See also: The Global South’s lost dream of mediated peace in Ukraine]