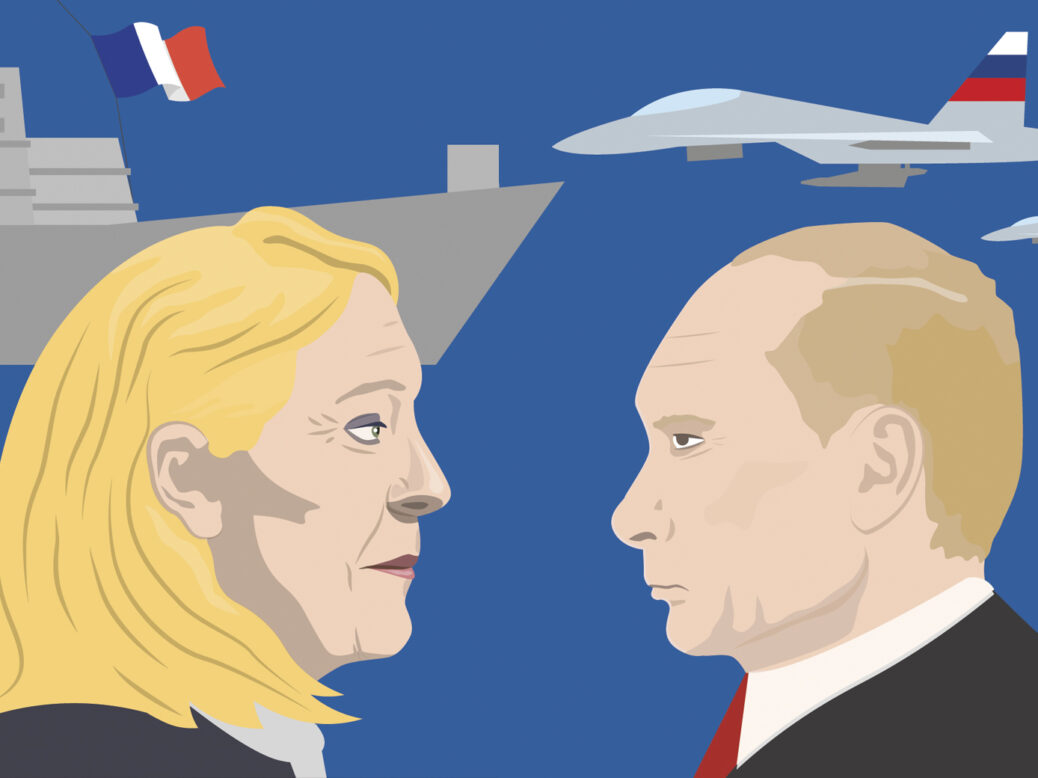

PARIS – In the end, the most striking image of Marine Le Pen’s press conference on foreign policy on 13 April came not from the far-right leader herself. Instead, it was the Green councillor Pauline Rapilly Ferniot, who, brandishing a photo of Le Pen and Vladimir Putin shaped like a heart, was muscled down to the ground and dragged out by a member of Le Pen’s security team. (Le Pen, embarrassed by how the brutal attitude to protest clashes with her new, softer image, later falsely claimed the man who dragged Rapilly Ferniot out was a member of the police rather her private security detail.)

La vidéo de l’évacuation d’une pertubatrice de la conférence de presse internationale de @MLP_officiel. pic.twitter.com/X1OdcGSVV5

— Augustin Lefebvre (@AugustinLef) April 13, 2022

Yet if the form of Le Pen’s conference probably did not end up being quite what she may have wanted, it was the substance that really mattered. While she argues that she has changed, her press conference in fact illustrated the continuity between old and new Le Pen, now closer than ever to power.

“As soon as the Russo-Ukrainian war has ended, I will argue for a strategic rapprochement between Nato and Russia,” Le Pen said, one of her few mentions of Europe’s gravest security crisis since the Second World War. The war ending on whose terms, she did not specify. Nor did she explain how she planned to convince other members of the Nato alliance, from the anti-Russian Baltic states and Poland to the US, to back a rapprochement with a country they view as waging an unprovoked war on a neighbour.

Le Pen would not quit Nato, as she has advocated in the past, she said. Instead she would quit the alliance’s integrated command structure, which France rejoined in 2009 after leaving in 1966 under Charles de Gaulle. “Independence, equidistance [between global blocs] and consistency” would be the three pillars of her foreign policy, she said.

France and Germany, the EU’s two largest member states, are often characterised as the driving force of the union. For Le Pen it is high time this came to an end. “We will end all projects in co-operation with Berlin,” she said, arguing that France needed to develop tanks and fighter jets by itself rather than with its neighbour. “Germany is the absolute negation of French strategic identity,” she asserted, citing Berlin’s allegedly pushing Paris to buy American military equipment.

Le Pen’s stated aim of leading France out of the EU and the euro is remembered as one cause of her defeat in the 2017 election. Today, she claims she no longer wants to do so. “Frexit is not our project,” Le Pen asserted, insisting instead that she wanted to “transform the EU into a European alliance of nations”, jargon for a looser grouping of governments.

In practice, Le Pen reaffirmed plans to inscribe the primacy of French law over European law in the French constitution. This move, similar to a decision last year by the Polish Constitutional Court on the supremacy of national law, would further gut European integration of its substance. It would not be a formal withdrawal from the EU but Le Pen’s critics will say that she would lead France out through the back door, as Emmanuel Macron, the president, recently alleged.

“If Le Pen-style disrespect for EU law and the authority of the European Court of Justice was to become more widespread and gain the support of the other EU member states, the very foundations of EU law could be in danger,” said Jakub Jaraczewski of Democracy Reporting International.

On question after question, Le Pen showed her ambitions to be in line with what her party has always advocated, if occasionally moderated. From gutting EU integration of its substance, to equidistance between the US and Russia, to ending co-operation with Germany and quitting Nato’s unified command structure, Le Pen’s press conference showed her to be a would-be leader whose fundamental instincts remain isolationist and tilted towards Russia. They indicate a leader who, if elected, would chart a foreign policy course drastically different to any recent French president, with potentially seismic implications for the EU, Nato and the world.

[See also: Will Sweden join Nato?]