The Covid-19 pandemic, which has resulted in more than 13 million cases worldwide and nearly 600,000 deaths, is accelerating, not receding. Against the virus epidemiologists have consistently agreed there is only one long-term defence: herd immunity. The dispute has been over whether this can be achieved without a viable vaccine.

Sweden avoided a strict lockdown but the early results there are not encouraging. The country has recorded a high death rate compared to other Scandinavian countries and unemployment has risen to 9 per cent; the economy is forecast to shrink by 4.5 per cent (figures comparable to some of its more stringent neighbours). As the wave of new lockdowns in the United States has demonstrated, “saving the economy” and defeating the virus are not contradictory but mutually dependent aims. Only once Covid-19 has been tamed will normal economic life resume. The greatest stimulus that any government can provide is a successful vaccine.

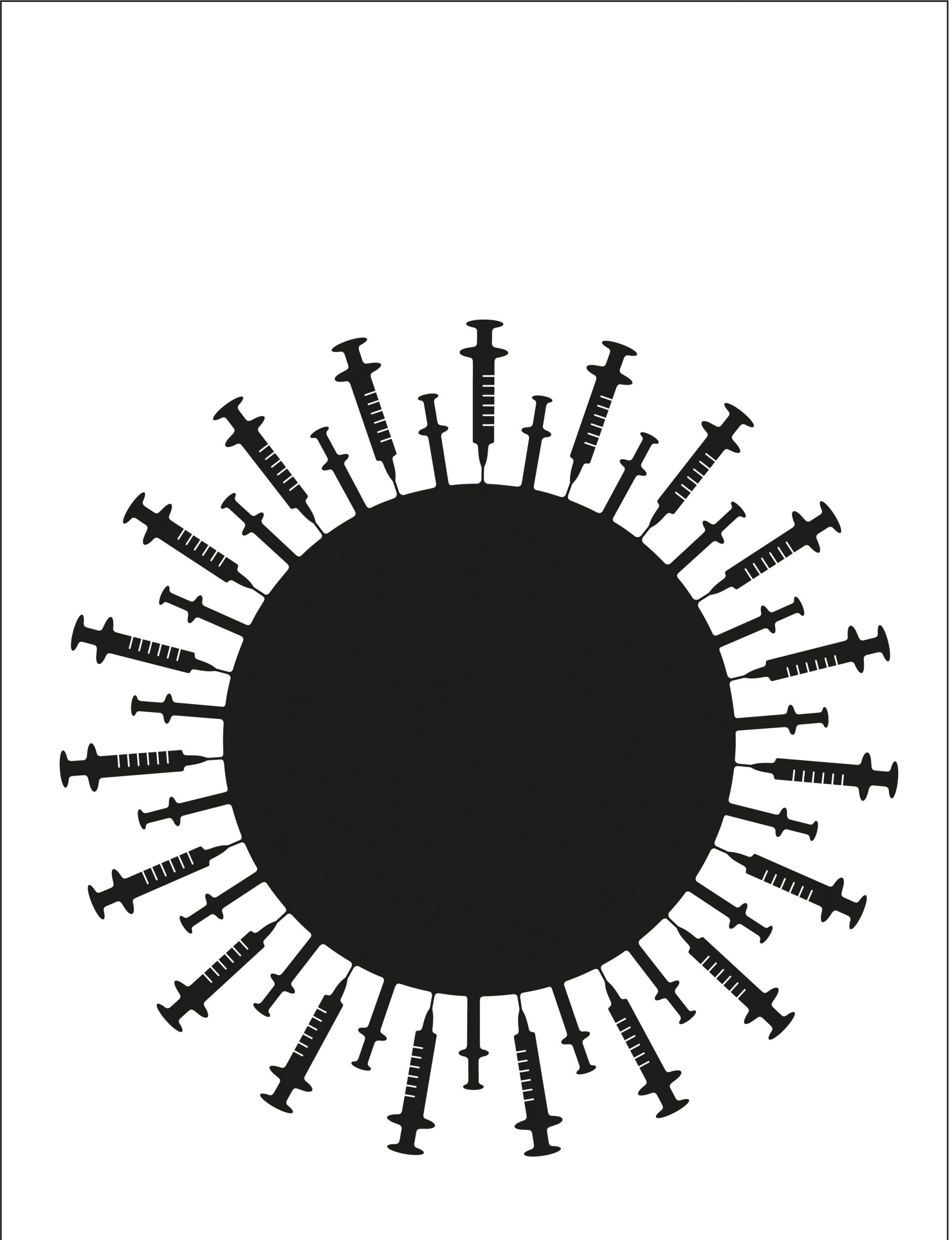

As Anjana Ahuja writes in this week’s cover story, this is the quest that scientists are now immersed in (with as many as 25 Covid-19 vaccines moved into clinical trials). “There is a growing sense of optimism that a success story lurks somewhere in these laboratories and that a vaccine could emerge this year,” she notes.

In northern Italy, doctors and researchers have found that the long-term effects of Covid-19, even among those who suffer mild infections, could be far worse than originally thought. Psychosis, kidney disease, strokes and spinal infections have been identified among former patients. As our medical columnist Dr Phil Whitaker wrote in last week’s print magazine, so-called long Covid sufferers can endure debilitating symptoms, such as chronic tiredness, months after their expected recovery date.

But developing a vaccine is far from the only challenge. It must then be produced in sufficient quantities and distributed equitably. The US has already raised the spectre of “vaccine nationalism” by monopolising stocks of remdesivir, an antiviral drug which can hasten recovery from the disease. The German government has wisely acquired a 23 per cent stake in CureVac, a national company working on a vaccine, possibly in order to forestall a foreign takeover attempt. Covid-19 has, once again, demonstrated the importance of national resilience and the perils of excessive foreign or private ownership of essential national assets.

Yet cross-border cooperation is also necessary. The British-Swedish company AstraZeneca, which defied a hostile takeover bid by the US’s Pfizer in 2014, has committed to supplying up to 400 million doses of the Oxford University vaccine to European countries at no profit. Imperial College London has established a social enterprise to provide its vaccine at reduced cost to the UK and low- and middle-income countries. This is not mere altruism: in an era of globalisation, splendid isolation is an illusion.

The sobering reality that the world must face is that a vaccine may never be developed; up to 30 per cent of all common colds are caused by coronaviruses and there are no vaccines for them. Rather than defeating Covid-19, we may be forced permanently to contend with it.

The threat of this coronavirus, and future pandemics, will reshape Western societies. Governments will need to invest more in public health and preventive measures (reserves for public health spending in England fell by 30 per cent from 2015 to 2019). Essential industries imperilled by social distancing will require subsidy and the state may, once more, be forced to act as an employer of last resort. Face coverings, already a cultural norm in much of Asia, may endure beyond the crisis. In short, the West is moving (or one hopes it is) towards a model in which the protective state trumps the unfettered free market, and in which atomised individualism gives way to greater social solidarity.

If there is hope it lies not just in the possibility of a vaccine but in the qualities demonstrated throughout the crisis: kindness, altruism and resourcefulness. It is these values that should shape the world to come.

This article appears in the 15 Jul 2020 issue of the New Statesman, Race for the vaccine