There is no shortage of companies announcing plans to achieve net zero emissions. Marks & Spencer (M&S), AstraZeneca, Tesco and EY are just a few of the well-known British businesses that have promised to slash their emissions in line with global targets to prevent CO2 levels rising more than 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels by 2050.

But such companies also invest large sums elsewhere, through their pension schemes. Many companies that have announced net zero plans for their businesses are still investing huge amounts in fossil fuel companies, steel companies and other polluting industries on behalf of their workers.

It is the corporate face of a problem with which many individual investors have grappled: should we sell our oil and gas stocks, and only invest in renewable energy firms? Or should we do more to stay engaged with the companies of which we are shareholders, and vote for them to do more on climate change? For companies whose pension schemes can be worth billions of pounds, these are important questions.

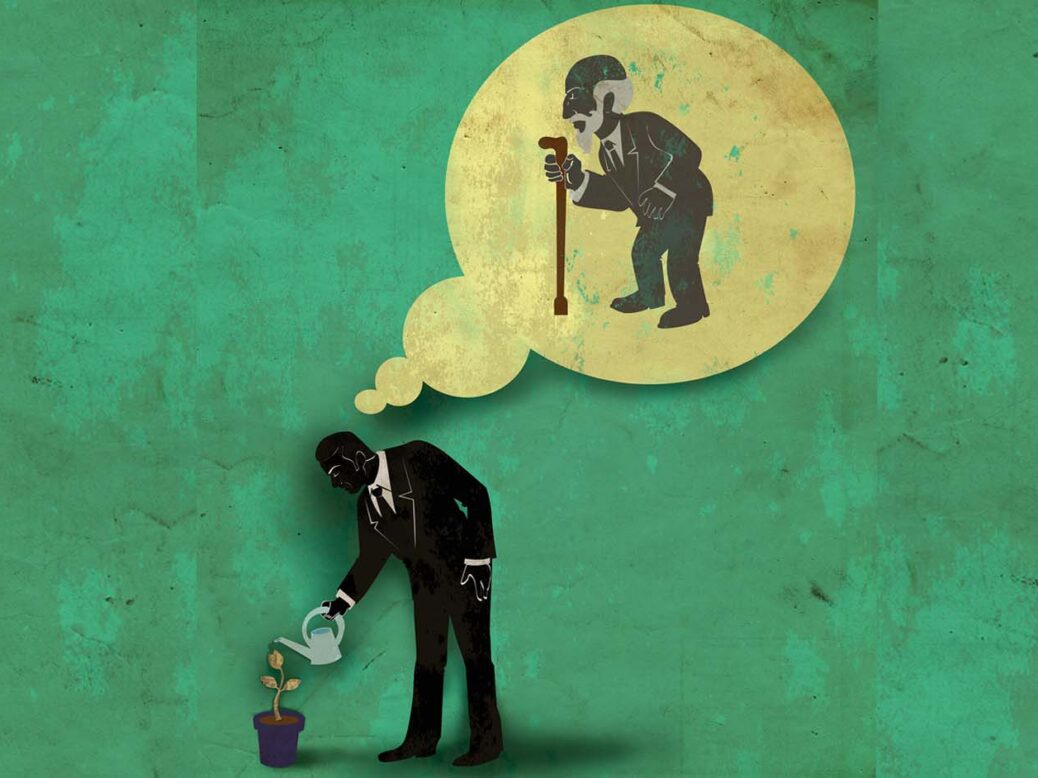

A new campaign, Make My Money Matter (MMMM), has been raising awareness of this issue. Tony Burdon, its chief executive, told me that “a lot of businesses are a bit like people – they’re looking at what they do as an operation, and they’re forgetting about their money”.

Many of the companies that have signed up to MMMM’s pledge to set a net zero target for their pension scheme are so-called B Corps: companies that have promised to balance environmental and social concerns with making profits. B Corp signatories include the baby-food maker Ella’s Kitchen, ethical bank Triodos and energy provider Octopus Energy. But there are larger companies too: Ikea, EY and Tesco have promised to cut their pension fund emissions to net zero.

In November, Tesco said that the investments in both of its pension schemes, amounting to more than £24bn, would be net zero by 2050. The chair of the Tesco pension fund, Ruston Smith, characterised this as primarily an investment decision: “Evidence shows that environmentally responsible, well-run companies are likely to perform better in the long term, and better-performing companies tend to be better investments.”

However, many other companies that have set net zero plans for their businesses have not yet implemented these in their pension schemes. MMMM highlights M&S, GSK, AstraZeneca, Diageo, Vodafone and Nestlé as just a few examples.

Sometimes, the companies have not yet considered this, or it is next on their to-do list. The trustee of the pension scheme for M&S, which has a net zero target of 2040, said it was “keen to align the pension scheme with the company’s climate ambition”.

Often, companies are addressing sustainability issues in their pension schemes at some level. A spokesperson for Nestlé says that its pension funds are addressing responsible investing “through a combination of measures”, while John Lewis says that its pension trustee takes sustainable issues into account, adding: “Investing responsibly is incredibly important to us.”

Some companies say privately that they are worried about putting pressure on a pension scheme that is supposed to be independently run. While younger workers or newer companies are likely to have so-called defined contribution schemes, where pension money is managed by an external fund manager that can be hired and fired by the company, older workers at larger companies are more likely to be in defined benefit schemes. These are run by trustees, who have a fiduciary duty to act independently and in the best interests of the pension scheme’s beneficiaries: the employees.

But there is debate over what “best interests” means. There is growing agreement that it does not mean maximising short-term profits, but that it should also take environmental, social and governance issues into account, as these can affect companies’ returns over the longer term – and if anything is investing for the longer term, it’s pension funds.

Investing in oil and gas companies is increasingly seen as riskier over the medium and long term, due to greater regulation in the sector that could harm profits. And in the shorter term, sustainable investments are doing better too. Morningstar, a fund ratings provider, found that three-quarters of so-called ESG (environmental, social and corporate governance) indices – which strip out less sustainable companies – outperformed their “normal” counterparts in 2020, while a still greater proportion (88 per cent) beat their benchmarks over the past five years.

Another issue is what “net zero” really means for a pension scheme, or for an investment fund that holds a lot of different companies. A company itself can tot up its emissions across its various activities, but there is no agreed method for how to do this for lots of different companies that might all have net zero targets in different years – from 2035 to 2050, for example.

Some analysts try to assign a “temperature” to a company, based on its current emissions vs its targeted emissions. MSCI, an index provider, provides an analysis every three months of how the world’s biggest companies are doing on climate change targets. For example, Royal Dutch Shell, which has set a net zero target for 2050, has an implied temperature rise of almost 2.1°C. ExxonMobil, which has no net zero target, is on a path for over 4°C. Overall, MSCI calculates that less than half of listed companies align with a 2°C temperature rise, and less than 10 per cent align with a 1.5°C temperature rise. At present, it calculates emissions of listed companies would cause temperatures to rise by 3°C above pre-industrial levels.

Companies in the UK will be required to report their climate risks from 2022, though the setting of net zero targets remains voluntary. But this may make it easier for investors to work out which companies are riskier from a climate change perspective and which will cause their portfolios to be “hotter”.

But Mark Lewis, head of climate research at Andurand, a hedge fund, said that the lack of methodology around calculating how hot portfolios are is something that the financial industry needs to address.

For now, a lot of the work in trying to cut the emissions in any investment portfolio, whether a company pension scheme or your own individual investments, involves trusting the company that it will hit its targets on time, and holding it to account if it doesn’t. But with more and more investors thinking about whether their portfolios are net zero, pressure on companies to do better will only increase.

Alice Ross is the deputy news editor of the “Financial Times” and the author of “Investing to Save the Planet” (Penguin).