A few weeks after watching the 2012 Ironman World Championships in Hawaii, a punishing race in which amateur athletes complete a 2.4-mile swim, followed by a 112-mile bike ride and then a 26.2-mile run, the Harvard human evolutionary biologist Daniel Lieberman flew to a remote part of Mexico to research the Tarahumara Native Americans, a people renowned for their long-distance running.

During ceremonial races the Tarahumara can run up to 80 miles while kicking an orange-sized wooden ball. When Lieberman arrived, with lingering memories of brutal Ironman training regimens, something struck him as odd. Apart from during their famous races, he never saw anyone running. The Tarahumara would laugh at Lieberman, a marathon runner, when he went out on jogs. He would ask them how they trained for their races. “Why,” one man replied, “would anyone run when they didn’t have to?”

“That got me thinking that just as so many other things in the modern world are weird and strange, so is exercise,” Lieberman told me, when we spoke via Zoom. His first popular science book, The Story of the Human Body (2013), argued that many of the chronic, non-infectious diseases afflicting the affluent West, such as diabetes, heart disease and certain cancers, are “mismatch diseases”, evidence that we are biologically ill-suited to our modern lifestyles.

Exercise is often proposed as a way to protect against these illnesses, but it is itself a curious modern phenomenon. Our hunter-gatherer forebears were much more active than the average 21st-century office worker, but with the exception of dancing and other communal rituals, they were not inclined to expend more energy than they needed to in order to survive. In other words, it’s not a sign of laziness if you struggle to find the motivation to work out; it’s human nature.

“The idea that if you don’t naturally want to get up and run five miles there’s something wrong with you is not right, but that’s how we treat people today,” Lieberman said. “So I wanted to write an anti-bullshit book about a topic that’s confusing and problematic, but is also important.” The result is Exercised: The Science of Physical Activity, Rest and Health, which uses his research into human evolution to interrogate ideas and misconceptions about health and exercise. Is sitting as bad for one’s health as smoking? he asks. Should you aim for eight hours of sleep a night? How far should you walk a day?

Lieberman divides his time between field research in isolated, hunter-gatherer communities and his lab, where he studies human and animal physiology for clues to our evolutionary inheritance. Why, his research tries to answer, is the human body the way it is?

One of his most influential scientific papers, published in Nature in 2004, was inspired by an experiment in which he placed pigs on treadmills to observe them running. His colleague, Dan Bramble, observed the pigs’ heads bobbed around a lot as they ran. Dogs, horses and other animals adapted for running possess a nuchal ligament in their neck that holds their head still. Humans have this ligament too, and other aspects of our musculoskeletal structure, as well as our ability to regulate our body temperature by sweating, suggest that humans evolved to run.

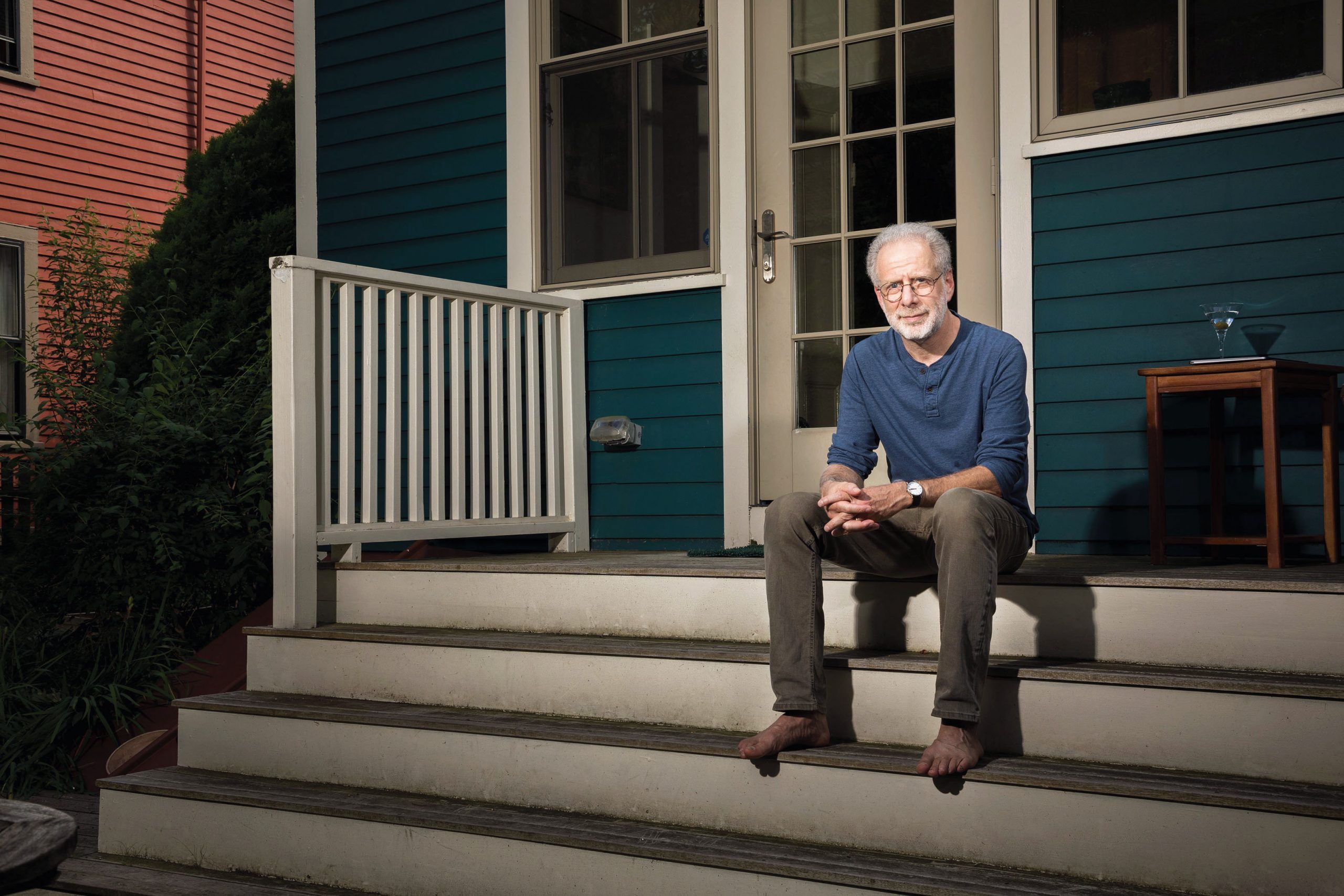

Lieberman argues that we are born runners, and observes that although we struggle to outpace many animals over sprints, we can outrun them over longer distances. He believes our ancestors practised “perseverance hunting”, chasing game over vast distances until it tired. Four years ago, Lieberman, who is 56, took part in a 25-mile “man against horse” race in Arizona: he beat 40 of the 53 horses and completed the mountainous course in four hours and 20 minutes. Lieberman likes to run barefoot or in specially designed “minimal” shoes, which research finds reduces the likelihood of injury. This has earned him the nickname the “barefoot professor”.

“People are confused about many aspects of health and disease. That’s because we medicalise it, we commercialise it, and we don’t give them the truth sometimes because we’re afraid to give them the complexities,” he said.

Exercised embraces these complexities. Take sitting, for example: long periods of inactivity are bad for you, they can cause your blood sugar to rise, increase your body fat and trigger dangerous inflammation, but sitting is also a normal thing to do. Researchers who applied accelerometers to hunter-gatherer tribes and Amazonian farmer-gatherers found they were sedentary for between five and ten hours a day. That’s significantly less than the average American who, according to one study, sits for 13 hours a day, but it suggests that modern couch potatoes can benefit from relatively minor tweaks to their lifestyle.

Lieberman believes that staying active while sitting (even fidgeting counts) and getting up a few times an hour makes a big difference. He is convinced that our inactive lifestyles are killing us, and describes Exercised as “a quixotic attempt to help the world”. When people visit the doctors, 70 per cent of the time it’s for illnesses that could be prevented by being more active, and exercise is proven to help treat mental illnesses such as depression and dementia, Lieberman told me. “I believe that if we could get people more physically active, we could in a simple way make the world a better place.”

This article appears in the 30 Sep 2020 issue of the New Statesman, Twilight of the Union