January. The glitter of Christmas is fading and the dark days bring a return, for many, to the isolating experience of home-working in a pandemic. Any joy felt at the brief bout of warm weather is tainted by fear of the climate change it signifies.

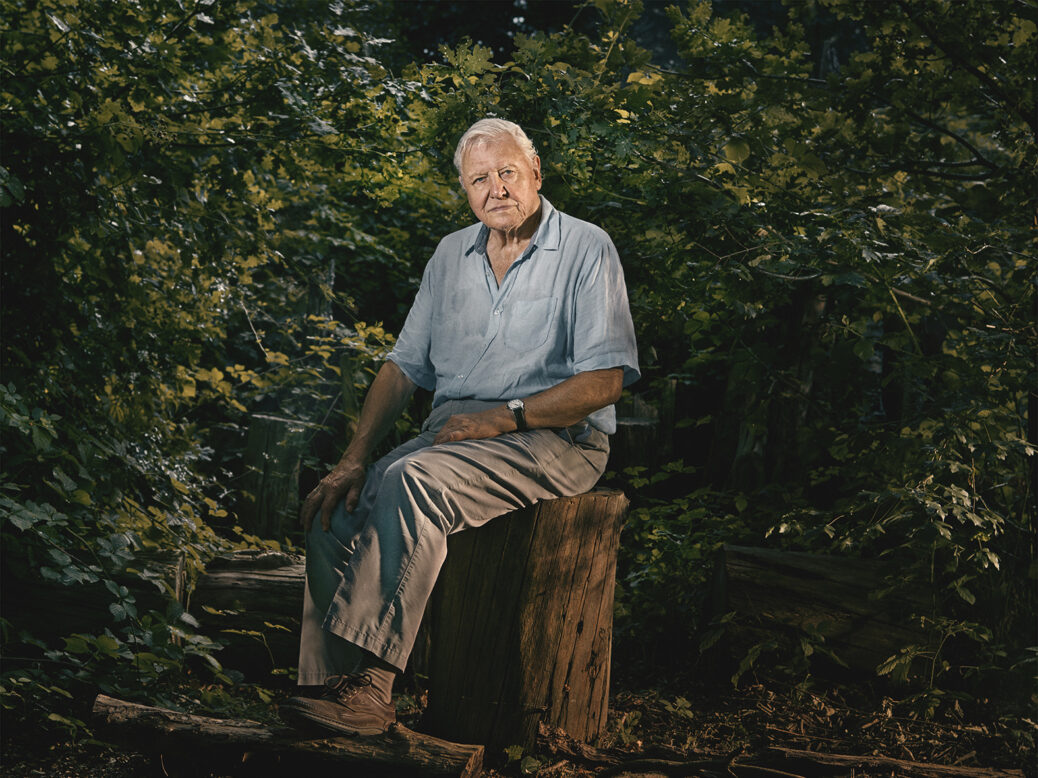

It can be easy to feel a little lost. Yet in the face of this dissolution arrives the latest documentary series from the seemingly inexhaustible David Attenborough: Green Planet. After the success of his series Blue Planet (2001) and Blue Planet II (2017), which explored marine wildlife up close, Green Planet turns to plants.

Like a perennial Father Christmas, the snowy-haired broadcaster is back on screen with insights into the primordial connections that link us all: “We depend on [plants] for every mouthful of food that we eat and every lungful of air that we breathe,” the opening to the first episode explains to viewers.

What follows is a sweeping, swerving, time lapse-filled journey into the secretive world of plant behaviour. From fungal spores to sky-reaching tendrils, bioluminescent fungus and pollinating bats, the layers of interconnection Attenborough finds between plants and animals are tonic for the wintry soul.

But exactly what kind of relationships does this series imagine plants to have with one another? In the opening sequence, Costa Rica’s seemingly peaceful rainforest is revealed to be a hidden “battlefield” of struggling, striving beings. Later on, we watch as vines “smother” their hosts and an outlandish “corpse flower” lures pollinators with the smell of rotting flesh. “Throughout this forest, plants are competing ferociously with one another to claim the light,” Attenborough proclaims dramatically.

The Darwinian emphasis of this language on competition, rather than collaboration, has led some viewers to query the programme’s approach. Plant species’ ability to trade resources or raise the alarm via expansive mycorrhizal networks of soil-based microbes is one of the most exciting areas of science today. Focusing so heavily on a combative lens seems out of place at a time when ecologists, such as Suzanne Simard, are unveiling plants’ incredibly social modes of being.

But human audiences respond to story arcs. Over the course of the first episode, quietly but urgently, the show shifts its emphasis from opposition to cooperation. Leaf-cutter ants may voraciously consume leaves, but they also sustain and are mutually supported by an underground fungus. Dipterocarp trees, meanwhile, release vast numbers of seeds simultaneously so that they can “face the dangers below together”.

“While the world of plants can be a ferocious battleground where species compete tendril-to-tendril for survival, there is also a tremendous amount of mutually beneficial collaboration under way at all times,” said Ian Dunn, CEO of NGO Plantlife. “If in any doubt that plants and fungi actively compete, and more importantly collaborate, in securing their success; this is the series for you.”

The episode also moves slowly from examples of plants competing with other plants, to the many instances in which plants are battling to survive in the face of human encroachment. At one point Attenborough laments that Darwin would be hard-pushed to describe any forest today as “un-defaced by the hand of man”, with 70 per cent of all plants growing within a mile of a road or an artificial clearing. By the end of the episode, this anthropomorphised focus on battles and struggles feels deeply appropriate in the face of the human threats to nature.

“The world’s rainforests are the richest and most dynamic systems on Earth – built on complex connections and relationships,” Attenborough muses, “but these connections, competitive or collaborative, are now becoming increasingly fragile.”

Unlike in his earlier films – think Planet Earth II’s failure to mention climate change in its Arctic scene – humanity’s impact on the natural world is at the heart of the story. In doing so, Attenborough’s deep-focus cinematography adds necessary wonder to these overcast days, and shows how the pursuit of a restored and thriving natural world may yet become humanity’s greatest collective struggle of all.

[See also: The strange spell of BBC Four’s “Winter Walks”]